New Observations Suggest Mid-Size Black Holes Exist

Finally, a black hole Goldilocks would appreciate. Mostblack holes are either incredibly massive or amazingly compact and lightweight,but now scientists have discovered a medium-sized black hole that's justright.

The finding is the most solid evidence yet for a long-sought-afterclass of intermediate-sized black holes, researchers said. These middleweights,at about 500 times the mass of the sun, could represent a missing link betweencommon stellar black holes, created by the death of a single star, and thesupermassive variety that can pack the mass of millions or even billions ofsuns.

The discovery is an object on the outskirts of the ESO243-49 galaxy, about 290 million light-years away. Astronomers detected astrong source of X-ray light, without a counterpart in optical light. Thesecharacteristics make the object much more likely to be a black hole than aforeground star or a background galaxy, researchers said.

"It's very difficult for us to say definitively 100percent this is what it is," said study leader Sean Farrell, an astronomerat the University of Leicester in England. "But certainly it?s thestrongest candidate that we've seen so far."

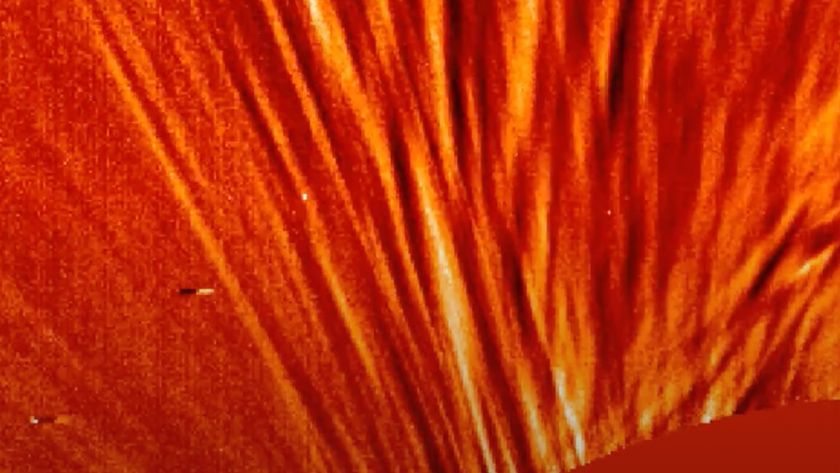

Black holes are objects so dense that once captured, evenlight cannot escape their gravitational draw. Since they reflect no light, theyare impossible to see directly. Astronomers can detect them through the strongradiation released by the whirlpooling disks of matter that fall into them,though.

In this particular case, the researchers think the X-raysthey observed are being emitted as friction heats up gas and dust in the disk.The discovery, made with the European Space Agency?s XMM-Newton X-ray spacetelescope, is detailed in the July 1 issue of the journal Nature.

Black holes in the smaller class form when a single massivestar dies and gravity forces some of its matter to collapse into itself.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists aren't sure about the origins of supermassiveblack holes, which populate the centers of many large galaxies. But onehypothesis suggests these behemoths are created when smaller black holes indense environments, such as globularclusters, collide and merge.

"This is where our result comes into play insignificance," Farrell told SPACE.com. "If we can show thatblack holes between the two mass limits do exist then that gives us a naturalprogression of how something can go from stellar to supermassive in size."

These intermediate black holes are relatively rare becausein most environments, such as a normal galaxy, stars aren't packed in tightlyenough to cause frequent collisions, Farrell said.

The newly-discovered intermediate black hole candidate wasseen on the edge of a galaxy, where a globular cluster could be expected toreside. Because the galaxy is so far away, the cluster itself wouldn't bevisible, but a middle-sized black hole's X-ray radiation could reach us.

Previous studies have found other medium-sized blackhole candidates, but these are more ambiguous because they are fainter inX-ray light, Farrell said.

"There have been a number of theories to explain high[X-ray] luminosities without needing intermediate mass black holes," hesaid. "Where our paper stands out is that we've got a detection of anultra-luminous source that is 10 times brighter than the previous recordholder. It gets increasingly difficult to explain this higher luminosity."

- Video: Chandra's Mid-Sized Black Hole

- Vote: The Strangest Things in Space

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.