Saturn's Rings to Disappear Tuesday

In a celestial feat any magician would appreciate, Saturn will make its wide but thin ring system disappear from our view Aug. 11.

Saturn's rings, loaded with ice and mud, boulders and tiny moons, is 170,000 miles wide. But the shimmering setup is only about 30 feet thick. The rings harbor 35 trillion-trillion tons of ice, dust and rock, scientists estimate.

The rings shine because they reflect sunlight. But every 15 years, the rings turn edge-on to the sun and reflect almost no sunlight.

"The light reflecting off this extremely narrow band is so small that for all intents and purposes the rings simply vanish," explained Linda Spilker, deputy project scientist for the Cassini Saturn mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Mysterious rings

The rings remain a bit of a mystery. Scientists are not sure when or how they formed, though likely a collision of other objects was involved.

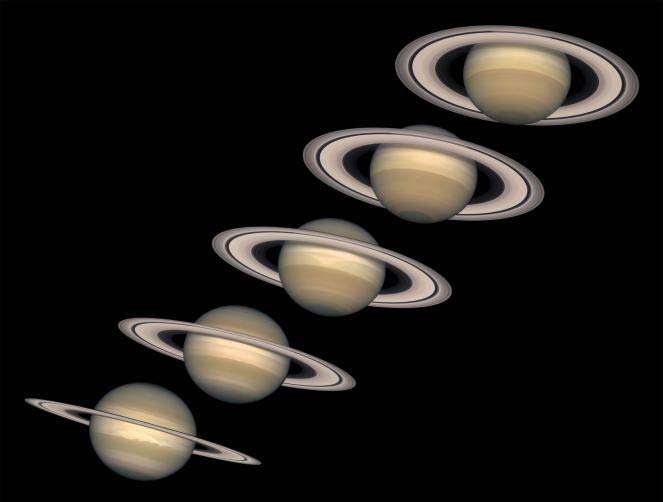

Saturn's equator is tilted relative to its orbit around the sun by 27 degrees – similar to the 23-degree tilt of the Earth. As Saturn circles the sun, first one hemisphere and then the other is tilted sunward. This causes seasons on Saturn, just as Earth's tilt causes seasons on our planet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While Earth goes around the sun once every 365 days or so, Saturn's annual orbit takes 29.7 years. So every 15 years, the attitude shift puts the gas giant planet's equator, and its ring plane, directly in line with sunlight. Scientists call it an equinox, and this one marks the arrival of spring to the giant planet's northern hemisphere. (On Earth, equinoxes occur in March and September.)

"Whenever equinox occurs on Saturn, sunlight will hit Saturn's thin rings, the ring plane, edge-on," Spilker said.

Galileo puzzled

Galileo Galilei was the first to notice the rings and their then-mysterious transformation in the 17th century. Through one of the first telescopes, which he built himself, Galileo discovered Saturn's rings. He didn't know what they were, though, since all he could see were two lobes attached to the planet like ears. He entered the newfound setup in his notebook as a tiny drawing, mid-sentence, to serve as a noun.

By December 1612, Galileo had studied the phenomenon for more than two years, and the lobes (he thought they might be moons) were getting thinner. Then they disappeared.

"I do not know what to say in a case so surprising, so unlooked for and so novel," he wrote in a letter.

Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens, using a better telescope, figured out what the rings were in 1655.

"Galileo had every right to be mystified by the rings," Spilker said. "While we know how Saturn pulls off its ring-plane crossing illusion, we are still fascinated and mystified by Saturn's rings, and equinox is a great time for us to learn more."

Up-close view

The edge-on setup casts shadows across the rings in a unique way that can reveal moonlets and other structures otherwise not visible.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has a front-row seat to the event.

Cassini is watching for topographic features – perhaps some tiny moons or warps in the rings, and it has already spotted some mystery features in the days leading up to the equinox. In one new image, an object seems to have punched through one of the rings, dragging material with it to leave a visible scar. The craft's near-infrared and ultraviolet instruments will be on the hunt for signs of seasonal change on the planet.

"We are not sure what we will find," Spilker said. "Like any great magician, Saturn never fails to impress."

- Gallery: Saturn at its Best

- Video: Rare Views of Saturn's Eclipsing Rings and Moons

- Gallery: Cassini's Latest Snapshots of Saturn

This article is part of SPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.