KAPOW! NASA Smacks the Moon in Search for Water Ice

Thisstory was updated 12:35 p.m. EDT.

WASHINGTON? A NASA probe slammed into the moon Friday, in a bid to blast out a curtain ofdebris in which scientists hope to detect signs of water ice.

The $79million LCROSS spacecraft, preceded by its Centaur rocket stage, impactedthe lunar surface at the large south pole crater Cabeus at 7:31 a.m. EDT(1131 GMT) in what NASA Chief Scientist Jim Garvin called "the ultimatephysics experiment."

"Wekeep finding evidence that there is water [on the moon]," NASAAdministrator Charles Bolden told SPACE.com here. To find more with LCROSS"would be incredibly good news. It would be another place we can sendhumans," he added. Bolden said he had been following the last steps of themission throughout the night.

The LCROSSprobe beamed liveimages of the moon as its Centaur rocket stage headed for impact beforemaking its own death plunge four minutes later. The two probes have crashed,mission managers assured, but whether LCROSS caught the much touted flash ofthe Centaur?s impact was not immediately clear.

?I cancertainly report there was an impact,? NASA?s principal investigator TonyColaprete told reporters after the $79 million lunar crashes. ?We saw theimpact, we saw the crater ? we have the data we need to actually address the questionswe set out to address.?

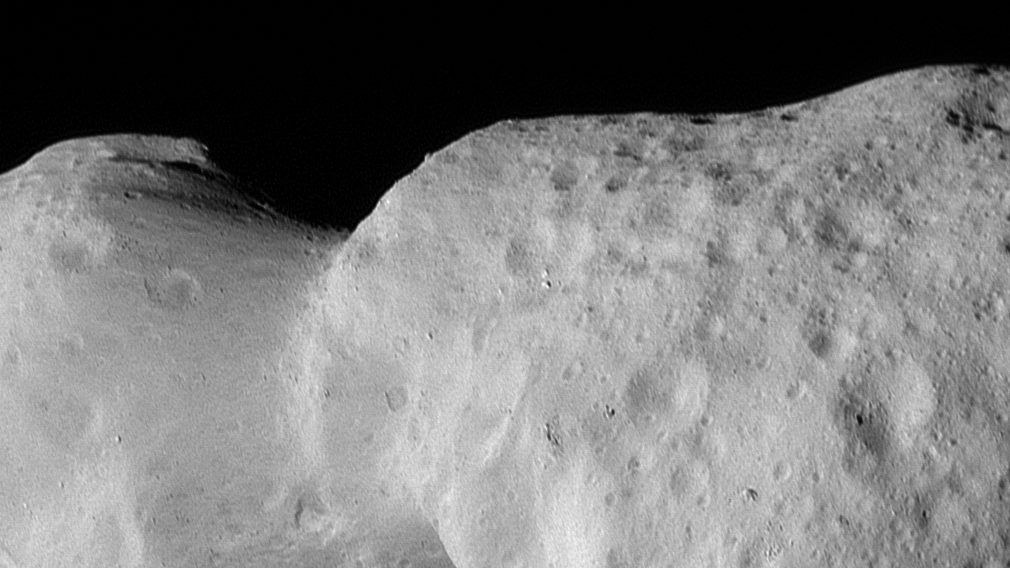

The targetcrater became larger and larger, with its bumpy relief becoming clearer, in thebroadcast images as LCROSS sped toward the moon. There were gasps and thenclaps from the Newseum crowd here as the viewing screen filled with the imageof the crater and then went white. Laughs followed as the Flight Director atAmes confirmed the successful impact and then proudly stood up in a televisedbroadcast.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Missionscientists watched the crash primarily from the probe?s operations center atNASA?s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., but astronomers andamateur skywatchers also tuned in at observatories and other sites around theworld ? including here at the Newseum, where more than 300 people watched theNASA impact broadcast on a huge 40-foot screen.

"Thisis the biggest screen I've ever seen," said one of the scores of people inthe crowd of NASA employees, members of the press and public, including severalbleary-eyed children.

Among thecrowd were Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin and Chip Cronkite, the son of lateCBS TV news anchor Walter Cronkite, to whom the mission is dedicated.

"Wehope this is just the first of many oases we find," Cronkite said.

NASAlaunched LCROSS ? short for Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite ?and the powerful Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) in June to hunt for evidenceof water and ice on the lunar surface.

Ice onthe moon

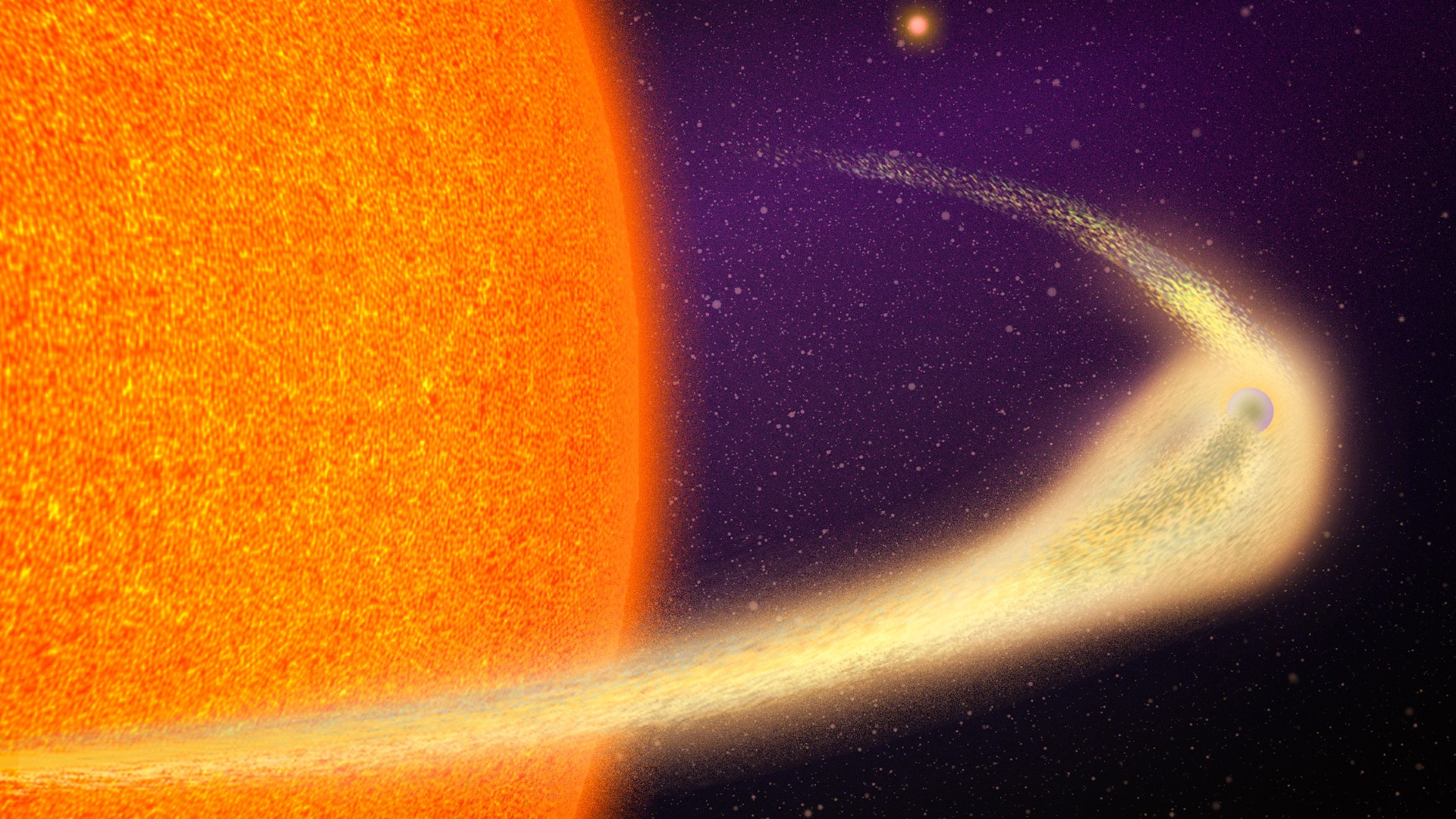

Scientiststhink that pockets of water ice might exist in the permanently shadowed cratersof the lunar south pole ? thought to potentially be the coldest places in thesolar system. Water has alreadybeen detected on the moon by a NASA-built instrument on board India's nowdefunct Chandrayaan-1 probe and other spacecraft, though it was in very smallamounts and bound to the dirt and dust of the lunar surface.

NASA plans toreturn astronauts to the moon by 2020 for extended missions on the lunarsurface. Finding usable amounts of ice on the moon would be a boon for thateffort since it could be a vital local resource to support a lunar base.

Even ifLCROSS does not turn up clear proof of water ice, that would be a major find,mission scientists said. It could mean that ice on the moon is not as uniformlydistributed as suspected, or that water exists in concentrations too low to bemeasured by LCROSS instruments ? which would have repercussions for its valueas a resource to astronauts, they added.

The LCROSSimpact was also watchedby several satellites that normally monitor Earth and spacecraft like theHubble Space Telescope, Sweden?s Odin observatory and LCROSS's sister spacecraft, the LROprobe, which were due analyze the debris after the impact to look for signs ofwater ice.

"Alleyes are on LCROSS today," Bolden said during remarks before the impact.

The crasheswere expected to kick up tons of moon dirt and carve a new crater within the60-mile (98-km) wide Cabeus. That new crater could be as large as 66 feet (20meters) wide and 13 feet (4 meters) deep. In a pass over the lunar south polelater today, LRO will image the LCROSS impact crater.

Some 350tons of moon dirt was expected to be blasted nearly 6.2 miles (10 km) above thelunar surface. Unlike past moon crashes by other probes, like Japan?s recentKaguya mission, LCROSS slammed into the lunar surface at a steep angle and wasslated to kick material up high enough to be illuminated by the sun as seenfrom Earth and other spacecraft.

Seasonedskywatchers on Earth equipped with 10 to 12-inch telescopes had a chance to spotthe crash on their own, if they knew where to look.

?There'snot going to be these grand, spectacular images of ejecta flying, kind of whatyou've seen in animations or cartoons,? Colaprete told reporters Thursday. ?It'sgoing to be more of a muted shimmer of light, but that muted shimmer of lightcontains all the information we need to answer our questions.?

Scientistsdon't know yet whether or not they've detected water in the LCROSS ejecta, asit is expected to take some time to analyze the data.

- Video - Why Bomb the Moon?

- The Greatest Lunar Crashes Ever

- POLL: Just How Important is Water on the Moon?

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.