Plenty of Solar Systems Like Ours Expected

WASHINGTON ? There's good news and bad news.

The bad news is that solar systems like ours are in the minority in the Milky Way. The good news is that's still an awful lot of potential twins out there.

Combining the results of a search for extrasolar planets in our galaxy and a method for calculating the likelihood that extrasolar planets exist, only about 15 percent of the stars in the Milky Way likely host systems of planets like our own, one astronomer said here today at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

"Now we know our place in the universe," said Ohio State University astronomer Scott Gaudi. "Solar systems like our own are not rare, but we're not in the majority, either."

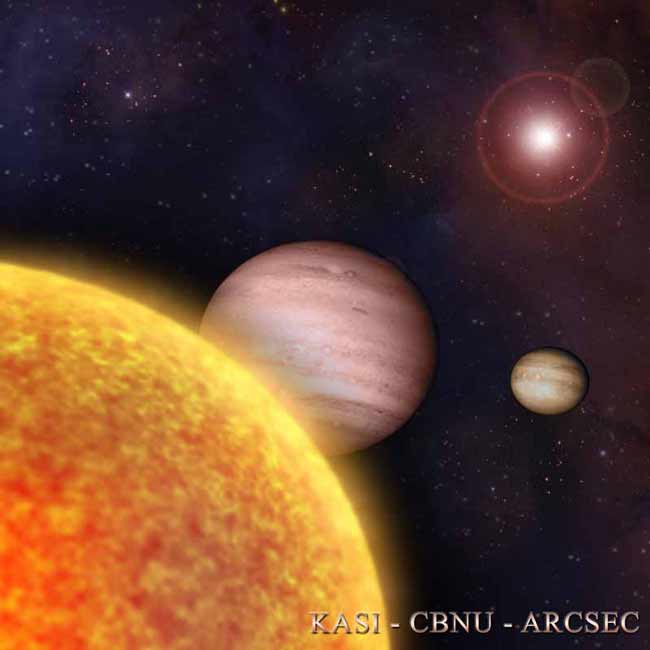

The speculation came partially from an exoplanet-hunting effort called the Microlensing Follow-up Network (MicroFUN). MicroFUN uses a method called gravitational microlensing, which occurs when one star crosses in front of another from the perspective of Earth. The nearer star magnifies the light from the more distant star like a lens. If planets happen to be orbiting the lens star, they boost the magnification briefly as they pass by.

Gravitational microlensing is particularly good at spotting giant planets ? analogous to Jupiter ? in the outer reaches of the galaxy.

The other piece of the puzzle came from Gaudi's doctoral thesis, written 10 years ago, on a method for calculating the likelihood that extrasolar planets exist. At the time, he came up with 45 percent of the stars in the galaxy having solar systems similar to ours.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In December 2009, another Ohio State astronomer, Andrew Gould, was examining a newly discovered planet from the MicroFUN project when he noticed a pattern in the planets discovered so far.

In the last four years, the MicroFUN survey has found only one solar system like our own ? a system with two gas giant planets resembling Jupiter and Saturn ? that was discovered in 2006 and announced in 2008.

"We've only found this one system, and we should have found about six by now, if every star had a solar system like Earth's," Gaudi said.

The slow rate of exoplanet discovery only makes sense if there just aren't as many distant planets out there to find. Gaudi and Gould determined that there must be a small number of systems ? around 15 percent ? like ours in the Milky Way.

The microlensing effort also suggests that our solar system is richer in planets than the average star. If all stars had planetary systems like ours, the effort would have found around 18 Jupiter- and Saturn-mass planets, but has instead found only six, Gaudi said.

Gaudi acknowledges that the percentage is based on an incomplete survey, but says it still gives astronomers a useful idea of just how many worlds might be out there.

"While it is true that this initial determination is based on just one solar system and our final number could change a lot, this study shows that we can begin to make this measurement with the experiments we are doing today," Gaudi said.

But while this calculation suggests that our solar system may be in the galactic minority, it still leaves room for plenty of other intriguing systems.

"With billions of stars out there, even narrowing the odds to 15 percent leaves a few hundred million systems that might be like ours," Gaudi said.

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Out There: Billions and Billions of Habitable Planets

- Video ? A World Like Our Own

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.