The first alien planet ever confirmed to come to our galaxy from another one could help scientists better understand the ultimate fate of Earth, and the demise of our solar system as we know it, researchers say.

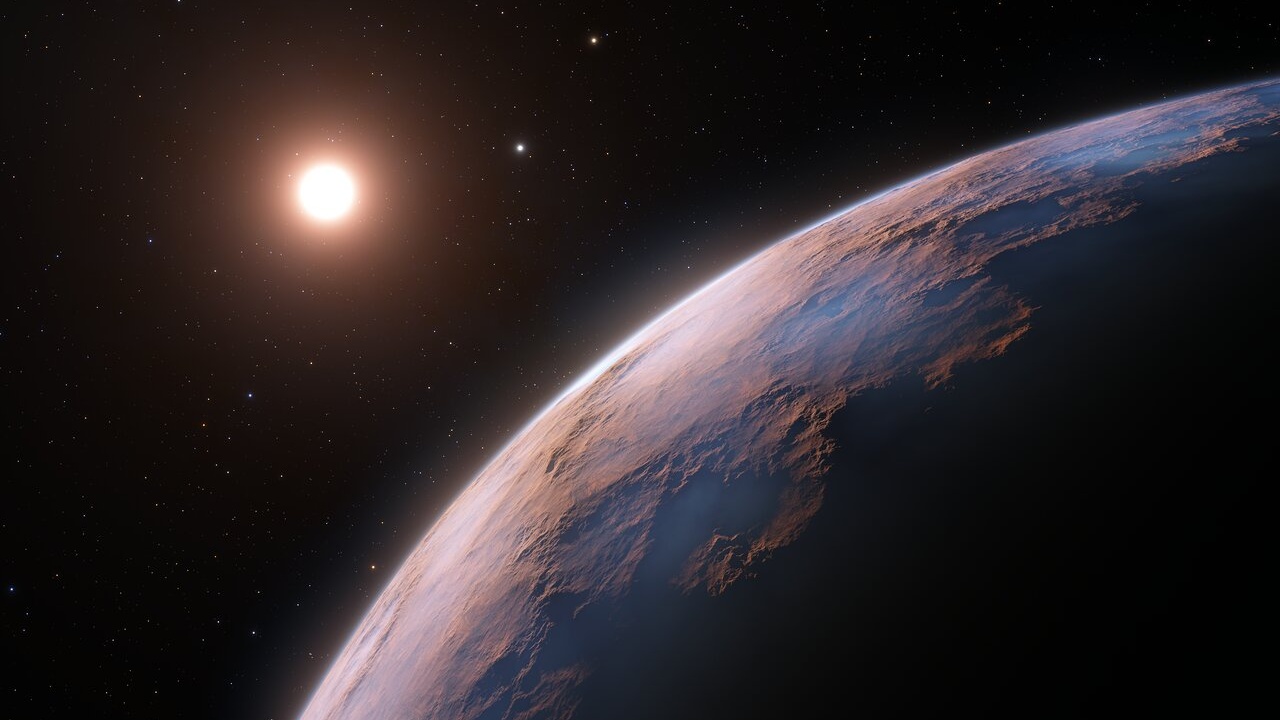

Astronomers today (Nov. 18) announced the discovery of the planet HIP 13044 b in the constellation Fornax, some 2,000 light-years away. The Jupiter-like world and the star it closely orbits, HIP 13044, were born in a nearby dwarf galaxy snatched up by our own Milky Way billions of years ago, researchers said.

HIP 13044 has already gone through the red giant phase of stellar evolution, a milestone our sun should reach in 5 billion years or so. The fact that the newly discovered exoplanet survived this dramatic event suggests some planets in our solar system might, too.

"It's very interesting to find planets that survive the red giant phase," study lead author Johny Setiawan of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, in Heidelberg, Germany, told SPACE.com. "We also would like to know: What kind of conditions make them survivors?"

Earth is not likely to be among such survivors: Its proximity to the sun probably means it will be consumed when our star expands during this phase.

Same star evolution path

HIP 13044 and our sun are on roughly the same stellar-evolution path — but HIP 13044 is a few steps ahead. The alien star was picked up by the Milky Way when our galaxy gobbled up an entire stream of stars that formed in a different, dwarf galaxy, researchers said.

The alien star has already gone through its red giant phase, in which sun-like stars bloat enormously after exhausting the hydrogen fuel in their cores. The sun will get there in 5 billion years or so, astronomers predict. [Video — How the Sun Will Die]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But while HIP 13044 b lived through its star's red giant phase, it did not emerge unscathed, researchers said.

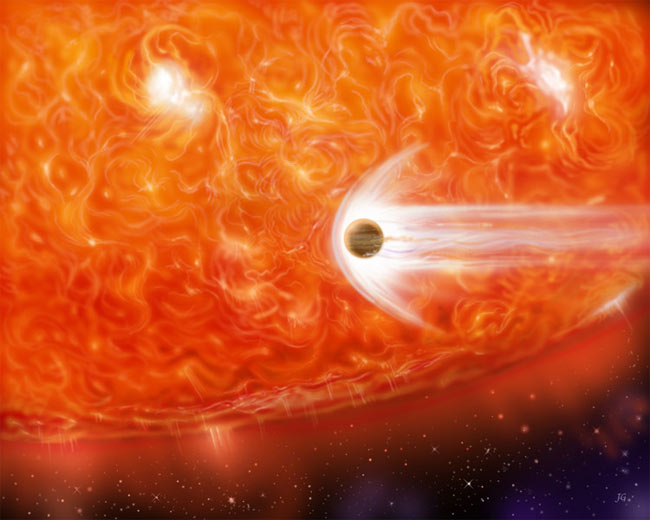

The huge stellar expansion likely caused the planet to spiral inward dramatically.

HIP 13044b now orbits extremely close to its parent star, which has recently contracted again, the researchers added.

At its nearest approach, the planet comes within about 5 million miles (8 million kilometers) — just 5.5 percent of the distance between Earth and the sun.

The planet could not have been so close all along, researchers said, or it would have been destroyed when HIP 13044 swelled up. Instead, friction from the red giant's gigantic envelope probably caused the planet to lose momentum and circle closer and closer over time.

A fiery death

Any planets closer to the star would not have been so lucky. They would have been swallowed up as the star HIP 13044 bloated outward, researchers said.

This may indeed have happened, because the star is spinning faster than expected, suggesting it gobbled up the mass from some of HIP 13044 b's planetary companions, they added.

The same fates could unspool in our own solar system — and the results for Earth wouldn't be pretty. Along with the other interior planets (Mercury, Venus and Mars), Earth is likely to be destroyed when our sun swells up, researchers said.

The gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) might survive — for a while. However, they, too, are likely to die in the end, researchers said.

So will HIP 13044 b: Its star is due to expand again in the next phase of its stellar evolution — and now the alien planet is probably too close to make it through.

"Outer planets will probably move inward," Setiawan said. "But in the end, they will also be engulfed."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.