Mystery Origin of Milky Way Galaxy's Gas Revealed

Like all creative processes, star formation requires the right materials: in this case, sufficient gas to bring a star to life. But scientists who study our Milky Way galaxy have been unsure where the necessary matter was coming from.

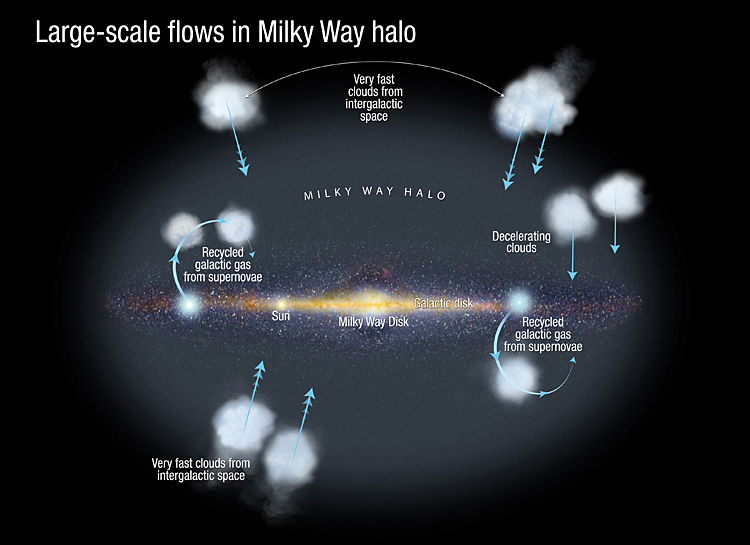

New research has revealed that clouds of gas in a spherical area called the halo that surrounds our galaxy could be massive enough to provide a large chunk of the gas required.

These fast-moving gas clouds, known as high-velocity clouds, or HVCs, surround the Milky Way. Gravity funnels them into the galaxy, where they become fodder for new stars. But astronomers have struggled to determine how big a role they play in star formation.

A pair of astronomers from the University of Notre Dame used the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph and the Space-Telescope Imaging Spectrograph on the Hubble Space Telescope to measure just how large the HVCs are.

"The first part of the study was to pinpoint the distance of gas clouds," lead scientist Nicolas Lehner told SPACE.com. "For this, we need stars." [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

Lehner and his colleague, Christopher Howk, selected 28 stars at random. The only criterion was that the stars could be seen by Hubble's instruments, and that they were at least 5,000 light years above the galactic plane. This took them higher than a previous study, which failed to locate any HVCs.

The two examined the material between the sun and each target, searching for clouds of gas that shone against the background star. Roughly half the stars studied revealed an HVC lying in the foreground.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As the light comes from the star to us, it's going to go through the gas cloud," Lehner said.

Because the distances to the selected stars were known, the astronomers could figure out how far away the clouds were. Most of the stars were cosmologically close, around 35,000 light-years from Earth. Knowing the distance allowed the scientists to determine that each cloud was, on average, a hundred million times the mass of the sun.

The astronomers calculated that the clouds fell into the galaxy at a rate of about one solar mass per year. The Milky Way churns out somewhere between half to one-and –a-half solar masses of gas per year.

"There's enough mass in the galactic halo to sustain star formation in the Milky Way," Lehner said.

Origins

But this mass will last for only about 100 million years. What happens next will depend on the origin of the gas itself.

So where did these clouds come from?

"We don't exactly know," Lehner said.

Some of them were likely created within our galaxy. As dying stars exploded, the gas was thrust away from the supernovas with enough speed to push it outside of the Milky Way, where it formed clouds.

These clouds rain back down on the galaxy, much like water from a fountain falls to the ground after jetting upward. Other clouds come from outside the galaxy, as their chemical compositions reveal. These merge with the Milky Way.

Once the gas is inside the galaxy, it eventually becomes closely packed enough to ignite star formation. Because the clouds are so close, relatively speaking, it means that astronomers will be able to examine them and determine their chemical composition, and shine some light on their origin. This, in turn, could help clue them in to how stars form in the Milky Way.

Details of the study, which was posted online in August, will appear in the Nov. 18 issue of the journal Science, along with two related papers on gas in galactic halos.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd