New Comet Finding May Alter Theories About Life on Earth

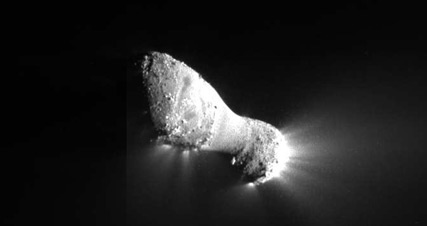

Comets may contain much less carbon than thought, whichcould rewrite what role they might have played in delivering the ingredients oflife to Earth, a new study suggests.

Researchers have detected carbon-loaded molecules in cometsin the past, including some simple amino acids, which are considered thebuilding blocks for life. The presence of these organic molecules in comets, aswell as the fact that comets regularly strike planets, suggested they mighthave helped seedour planet with the carbon-based materials needed to form life.

To learn more about the carbon in comets, scientistsanalyzed wide-field images of comet C/2004 Q2 (Machholz) recorded by the GalaxyEvolution Explorer (GALEX)satellite. They focused on the ultraviolet light shed by the envelope of dustand gas surrounding the comet's nucleus.

Carbon atoms on comets become ionized, or electricallycharged, when they are hit by enough energy from the sun. The researchersstudied radiation emitted by charged carbon atoms to determine how long ittakes most carbon on a comet to become ionized. They found that this processoccurs after only seven to 16 days ? much more quickly than thought.

This suggests that past research could have overestimatedthe amount of carbon in comets "by a factor of up to two," researcherJeff Morgenthaler, a space physicist at the Planetary Science Institute inTucson, told SPACE.com.

Scientists have known that sunlight can charge carbon. Thesenew results show how much the solarwind ? the gusts of electrically charged particles from the sun ? alsoinfluences carbon in space.

"This had been predicted earlier, but until now no onehad quantitatively put all the pieces together and done a measurement thatconfirmed it," Morgenthaler said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These findings "could rein in speculation as to what carbon-containingmolecules comets might have been contributing to Earth," Morgenthalersaid. By rewriting what scientists know of carbon levels in comets, thediscovery might also influence models of how these space rocks are formed.

"We are looking for trends in the compositions ofcomets as a function of their orbital dynamics," Morganthaler said."Orbital dynamics can tell us something about where comets came from; thisresearch helps provide a clearer picture of what they are made of. Together,they provide a view of the early solar system."

Morgenthaler and his colleagues will detail their findingsin the Jan. 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

- Supernova Explosions Offer Potential Spin on Life's Origins

- 5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids

- Video - Collision Watch: Scientists Track Comets That Could Slam Earth

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us