Cosmic Noise Could Improve Space Weather Forecasts

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A signal astrophysicists once dismissed as contamination ofX-ray observations could actually improve forecasts of dangerous space weather thatthreatens Earth.

Charged particles within the solarwind give off so-called soft X-rays when they collide with the magneticfield that shrouds the Earth. The soft X-rays have longer wavelengths and lowerfrequencies than their hard X-ray cousins.

This signal was once dismissed as local cosmic noise thatinterfered with space observatory surveys of hot, distant objects such assupernovas, until some scientists realized its significance for Earth.

Article continues belowMeasuring the soft X-ray emissions could allow scientists tobuild a real-time picture of what's happening with the planet'smagnetic field, also known as the magnetosphere, which protects Earthagainst solar storms. Past observations show that soft X-ray data changesalmost immediately in response to changes in the solar wind.

"It's not a question of advanced warning in this case,but rather getting the global view, ?that is knowing what is happeningeverywhere at once," said Michael Collier, an astrophysicist at the NASAGoddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

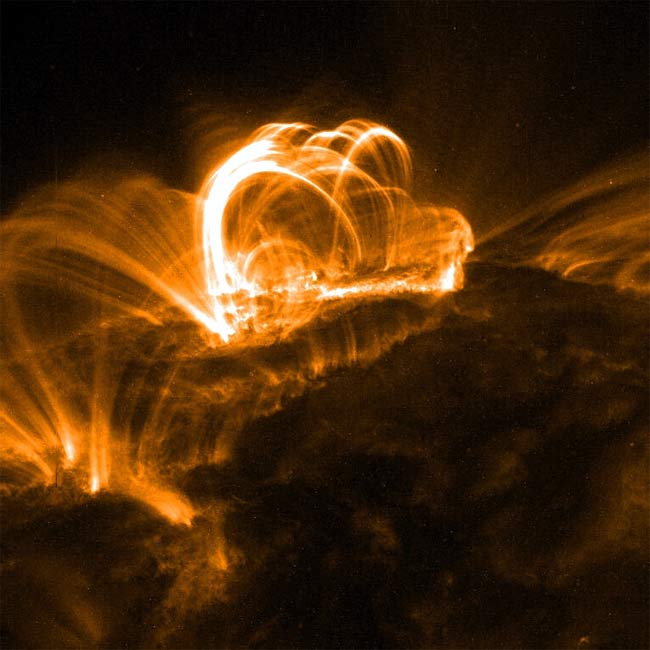

Having a complete, ever-changing view of the magnetospherecould not only boost spaceweather forecasts, but might also solve scientific controversies such ashow magnetic reconnection works. That phenomenon takes place when tangledmagnetic field lines merge and release energy in the form of heat and kineticenergy among charged particles.

Collier and his colleagues detailed their proposal in theJune 15 issue of Eos, the weekly newsletter of the American Geophysical Union.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

X-ray surprise

Such a use of soft X-rays seemed unthinkable two decades ago,because only very hot objects such as supernova remnants or stars typicallyproduce X-rays. That view changed when Germany's Roentgen Satellite spottedsoft X-ray emissions coming from the comet Hyakutake in the 1990s.

Scientists found that ionized versions of carbon,oxygen and hydrogen atoms in the solar wind ended up colliding with neutralatoms close to the comet and stealing an electron from the atoms. That made theions super-excited for a short period, before they relaxed and emitted theenergy as soft X-rays.

That same phenomenon also takes place when the solar windruns into the Earth's magnetosphere, Collier and his colleagues said. Theypoint to observations made by the European Space Agency?s X-ray Multi-Mirror(XMM) Newton spacecraft that revealed how the charged particles of the solarwind emit soft X-rays.

NASA's ChandraX-ray observatory also took advantage of soft X-ray data to build a pictureof how the solar wind flows around Mars and Venus.

But even if the existing soft X-ray telescopes havedemonstrated the "proof of concept" for how to image the Earth'smagnetosphere, Collier said that a new, dedicated mission would be necessary tomake full-time observations.

"A true magnetosheath imager, while relying on the sameobservational techniques applied in astrophysics telescopes, would require aredesign to achieve the wide field-of-view," Collier told SPACE.com.

The solar wind slows dramatically when it runs into the bowshock of the Earth's magnetic field. Some particles from the weakened solarwind still penetrate the middle region, called the magnetosheath, but most donot get beyond the next boundary called the magnetopause.

A new space weather vane

Having the X-ray imager in the right spot could providereal-time views of changes in the magnetosphere almost around the clock.Placing the imager at a special spot called the L1 Lagrange point between theEarth and the sun would allow the spacecraft to stay in a relatively fixedposition, held in place by the balancing gravitational pulls of the two largebodies.

Even a spacecraft in Earth orbit might allow for almost 24/7coverage, aside from a small part of the orbit where the imager ends up insidethe magnetosphere looking out, Collier explained.

That coverage matters especially for space weatherprediction models that try to forecast disruptive sun events. One solar flaresent out a wave of charged particles that knocked outthe power supply in Quebec and disrupted power and communications acrossNorth America during a March 1989 solar storm.

But almost any vantage point would still provide forgroundbreaking scientific observations, Collier noted. An X-ray imager couldhelp pinpoint the precise locations of the magnetopause and bow shock, as wellas uncover how solar wind energy flows around and through the magnetosphere.

"It really is like the blind men and the elephant: Existingheliophysics missions provide us very good observations of the trunk or thetail, so to speak," Collier said. "An imager will provide us theentire elephant."

- Images — Space Storms from the Sun, Mars Base

- Space Station Flies Through Big Space Storm

- Video Show — Attack of the Sun

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.