Cracks in the Universe: Physicists Search for Cosmic Strings

WASHINGTON (ISNS) ? Physicists arehot on the trail of oneof strangest theorized structures in the universe. A team ofresearchers haveannounced what they think are the first indirect observations ofancient cosmicstrings, bizarre objects thought to have contributed to the arrangementofobjects throughout the universe.

First predicted back in the 1970s, cosmicstrings are thought to be enormous fault lines that onceexisted in space.Not to be confused with the subatomic strings of string theory, cosmicstringsare widely believed by astrophysicists to have formed billions of yearsago,just moments after the Big Bang when the universe was still a soupymass ofextremely hot matter. As the universe cooled, defects formed betweendifferentregions of space that cooled in different ways, much like cracksforming in theice on a frozen pond. These defects in space were the cosmicstrings.

Although researchers have not yetdirectly observed thestrings themselves, the team believes they found evidence of themhidden in ancientquasars, enormous black holes that shoot out mighty jets oflight andradiation, found at the heart of many galaxies.

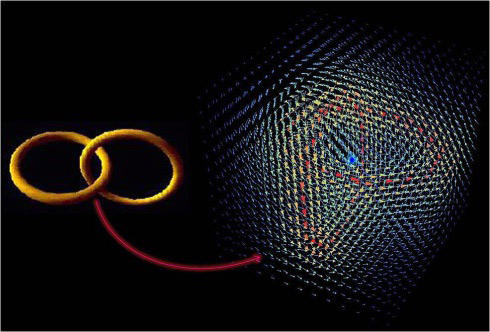

The presumed cosmic strings wereincredibly narrow, thinnerthan the diameter of a proton, but so dense that a string less than amile inlength would weigh more than the Earth. As the universe expanded, sotoo didthese strings until they either stretched across the known universe, orintoenormous rings thousands of times larger than our galaxy.

"Their magnetic field sort of hitchesa ride with theexpansion of the universe," said Robert Poltis from the University atBuffalo in N.Y. and lead author of the paper reporting the findings.

Poltis' team analyzed theobservational data of 355 quasarsthat reside in the far off corners of the universe. With carefulscrutiny ofthe light emitted by these quasars, it is possible to determine thedirectiontheir jets are facing in space. The team found that 183 of them linedup toform two enormous rings that stretch across the sky in a patternunlikely tohave formed by chance.

The team members think that the magneticfields of the two cosmic strings affected the direction thequasars arepointing. The strings themselves should have long since dissipated byemittinggravitational radiation as they vibrated; however the original effecton thealignment of the quasars would have remained.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The string itself is gone, but youget the magneticfield imprinted in the early universe," Poltis said. To check theirhypothesis, they modeled the theorized effects of the strings on theformationof quasars, and found their predictions closely matched theirobservations.

Poltis added also that they stillneed to conduct morefollow-up observations and analysis before they can be completely suretheyhave found evidence of the strings. The detection of a cosmic stringwould bean important cosmological discovery because of their theorizedimportance tothe formation of galaxies in the early universe. However, otherresearchers arecautious about the results.

Jon Urrestilla of the University ofthe Basque Country inBiscay, Spain, doesn't want to jump to conclusions too quickly. He saidthatPoltis' research is exciting because his team is making testablepredictions.

"It is still early to say that thiswork has discoveredevidence for cosmic strings. It is promising, the science is sound, butoneshould be careful. There are assumptions made that need be checked,"Urrestilla said, "But it is yet another piece to the puzzle, and themorepredictions we can make from the same basic science into presumablyindependenteffects, the closer we will be to detecting whether strings really werethere."

Tanmay Vachaspati from Arizona StateUniversity in Tempe, aleading expert on cosmic strings, said he thought that the observationoflined-up quasars was puzzling, but he was skeptical it was caused bycosmicstrings. He said that had the strings formed nanoseconds after the BigBang, they probably would have decayed so quickly that theirmagneticeffect wouldn't last until today.

"I don't see them staying arounduntil today to provideobservational signals," Vachaspati said.

Their paper was publishedin Physical Review Letters onOct. 11.

- HowBlack Holes Gobble Dark Matter

- Top 10Strangest Things in Space

- Video:Black Holes: Warping Time & Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.