Elusive Dark Matter May Be Hidden on Earth

Scientists are hot on the tail of one of nature?s mostelusive substances, the mysterious dark matter that is thought to make up thebulk of the universe. Many scientists think dark matter might even be hidingright under our noses here on Earth.

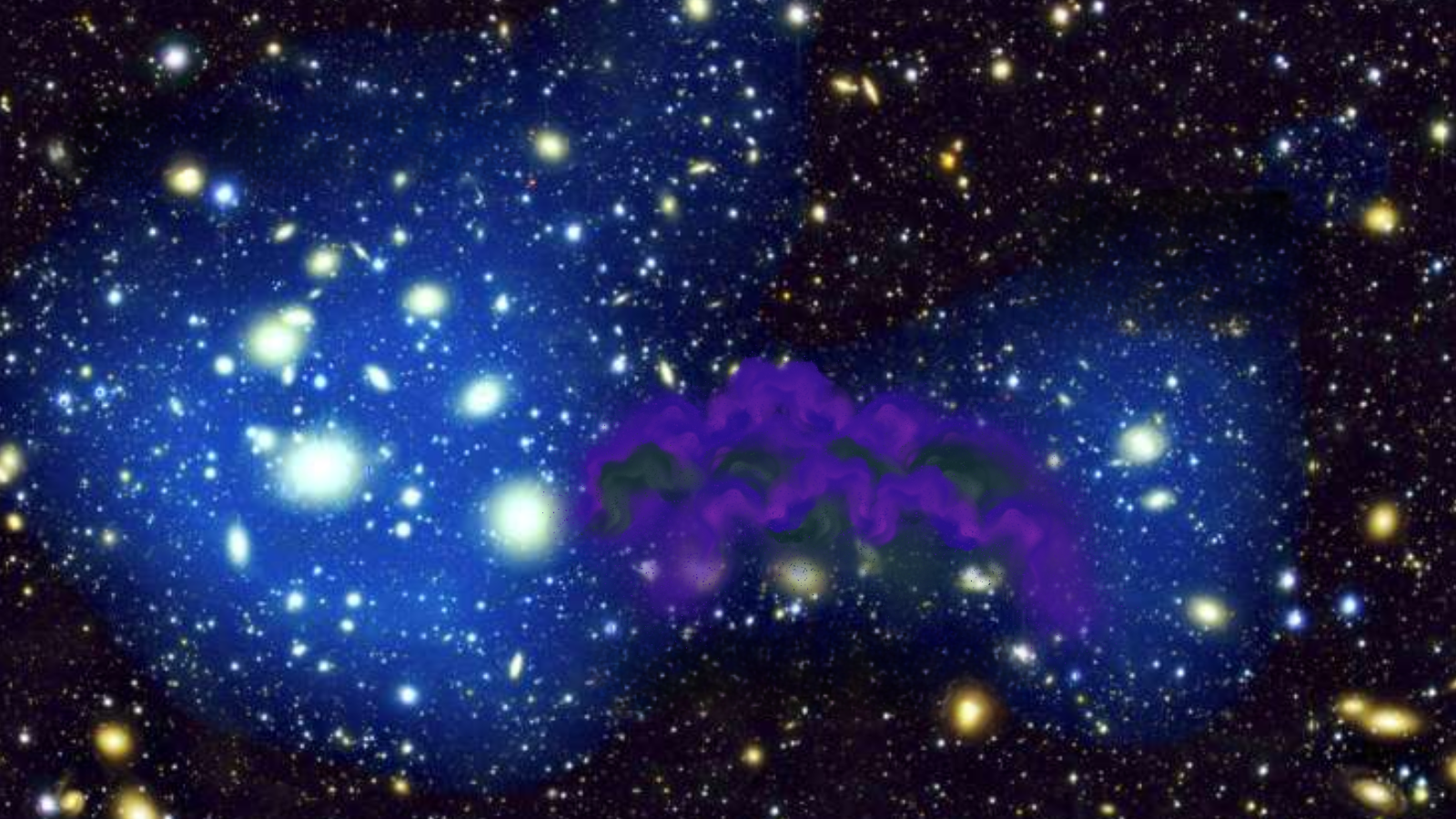

Dark matter is especially tricky to find because of its darknature. In fact, scientists don?t know what it is. It doesn?t emit or reflectany light, so the most powerful telescopes have no hope of spying it directly.It has been thought to exist since the 1970s based on observations of gravity?seffects on large-scales, such as among and between galaxies ? regularmatter can?t account for the amount of gravity at work.

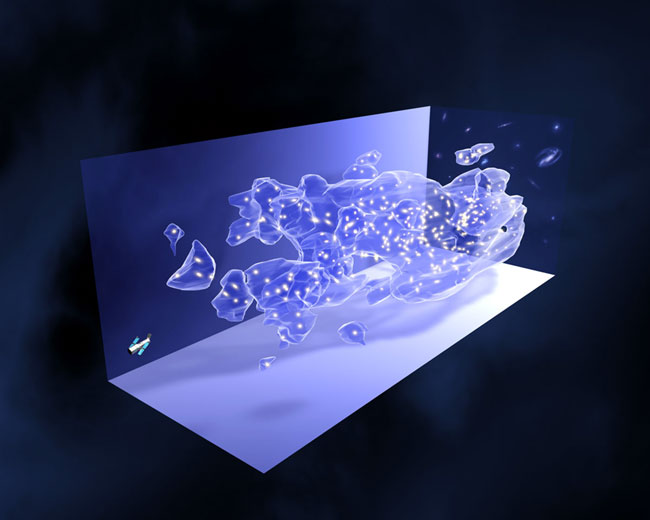

And darkmatter doesn?t often interact with most other matter, scientists theorize.One idea is that it flies right through the Earth, your house, and your bodywithout bouncing off atoms.

Some scientists have taken to underground searches in hopesof catching just a few out of the multitude of dark matter particles in a rareinstance of actually bouncing off of a regular particle.

?They?re just streaming right though us, and every once in whilethere?s an interaction,? said Angela Reisseter of the University of Minnesota,a member of a project called the CryogenicDark Matter Search (CDMS). She spoke this month at the meeting of theAmerican Physical Society in Washington, D.C.

Dark matter detected?or was it?

In a recent issue of the journal Science Express, Reisseterand her colleagues reported finding two possibleevents that may or may not be dark matter impacts on their detectors.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

?Our previous results have been no, no, no,? Reisseter said.?This is our first maybe ? that is all it is.?

The CDMS is buried in a mine in Minnesota underneath about766 yards (700 meters) of rock, plastic, lead, copper and other materialsdesigned to stop everything but dark matter from reaching the experiment ? thuscosmic rays and other particles that might be confused for dark matterparticles will mostly be eliminated.

The detectors themselves are basically small, hockey-puckshaped blocks of the elements germanium and silicon. If the nucleus from one ofthe germanium or silicon atoms is hit by a dark matter particle, then it willrebound and send a signal to the detector.

However the researchers can?t be absolutely sure that thetwo signals they measured were dark matter and not some other particle, whichthey call background. Two signals is just too few to be confident of, they said,because their calculations predicted about one false event from background.

?If it was one, we?d say ?Oh, it?s the background.? If itwas three you start to say ?Oh, it?s a signal,?? Reisseter said. ?We can?t callit background and we can?t call it signal.?

The CDMS team intends to keep running their experiment atever more sensitive levels in hopes that a more substantial signal isdiscovered.

Dark matter hunt goes on

Other attempts to track down dark matter on Earth havefocused on powerful particle accelerators that speed up subatomic particles toclose to the speed of light and then smash them together, hoping the incrediblyhigh collision energies create exotic particles, including dark matter.

But even with our increasingly powerful atom smashers, nosign of dark matter has yet been spotted.

?You have to ask why would this be?? said Sarah Eno of theUniversity of Maryland. ?Why would the particle that makes up most of the matterin the universe never have been seen in our accelerators??

One reason could be that they just aren?t powerful enough.Scientists aren?t sure how massive the dark matter particle might be, andcertain possibilities require extremely high energies to create them in thelaboratory. Or it might be impossible find at any accelerator.

?We don?t know for a fact that the dark mater particle is aparticle we would be able to produce and detect,? Eno said.

The best hope now could be a new particle accelerator ? the LargeHadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva, Switzerland ? that is the largest everbuilt. It opened recently and isn?t yet running at full speed. When it does,many are holding out hope that dark matter will finally be pinned down.

?It could be that now we have this new machine we?ll finallyhave enough energy to make this dark matter particle and see it in ourcollisions,? Eno said. She is a member of the Compact Muon Solenoid experimentteam at the LHC.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.