Found! Tiny Moon-Size Alien World Is the Smallest Exoplanet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

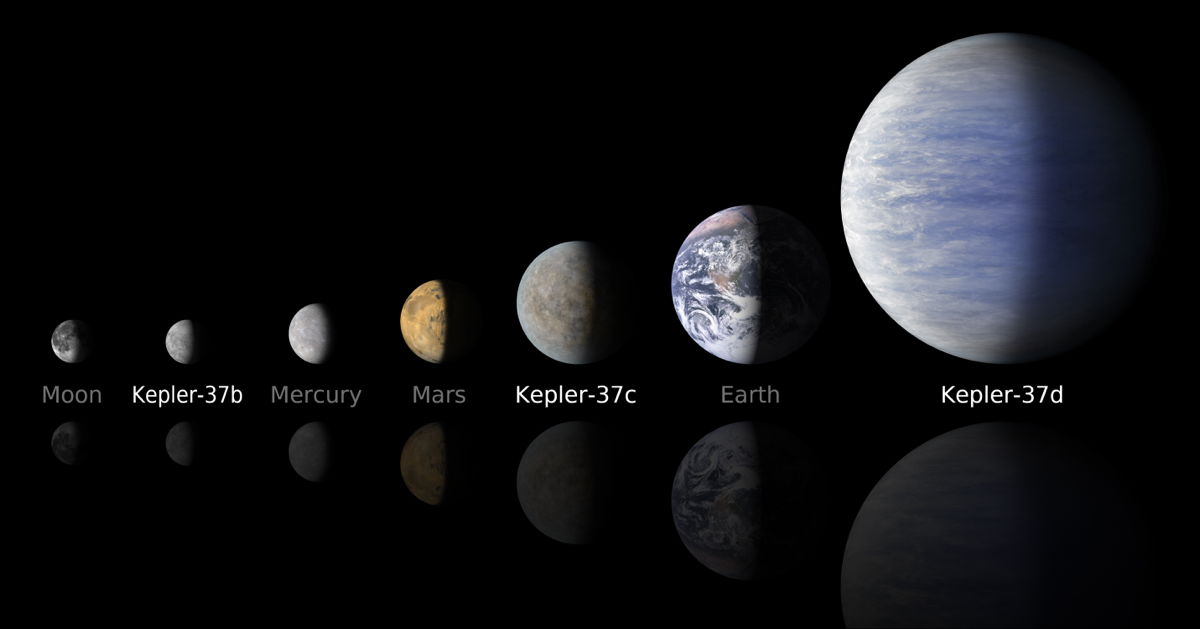

The discovery of a strange new world about the size of Earth's moon has shattered the record for the smallest known alien planet, scientists say.

The newfound alien planet Kepler-37b is the first exoplanet discovered to be smaller than Mercury. It whips around its parent star every 13 days and has a roasting surface temperature of about 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 Celsius), researchers said. It not a promising contender for life, they added.

Astronomers found Kepler-37b and two other, larger planets (called Kepler-37c and Kepler-37d) orbiting a star about 215 light-years from Earth using NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope. Finding such a small exoplanet with the Kepler spacecraft was a stretch, but some attributes of Kepler-37b's parent star made the discovery possible.

The star has few sunspots and is bright relative to its planet, making it easier for the Kepler spacecraft to spot the telltale dimming that takes place when a planet passes in front of its star, which scientists call a transit. That method revealed not just the presence of Kepler-37b, but its two siblings in orbits farther from the parent star than 37b. [Gallery: The Smallest Alien Planets]

"There are not many signals masking the transit," study leader Thomas Barclay of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., told SPACE.com. "What makes this exceptional was this dip of brightness was just 22 parts per million."

Too hot to host life

Kepler-37b and its siblings, 37c and 37d, are likely uninhabitable, scientists said. All three planets lie close to their parent star, well inside the Earth-sun distance (called astronomical units, or AU). One astronomical unit is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The moon-size Kepler-37b is so close to its parent star, at just 0.10 AU, that it likely has no atmosphere or liquid water on its surface. The next planet out, Kepler-37c, is slightly smaller than Earth and may have an atmosphere, but it orbits the star at 0.14 AU — well outside the star's habitable zone in which liquid water could exist on the surface.

The biggest planet in the newfound alien solar system is Kepler-37d. It is about twice the size of Earth and orbits the parent star at a distance of 0.2 AU.

"This could hold an atmosphere, but it's unlikely to be a rocky planet — more likely to be gassy — simply because of its size. It could hold some kind of liquid at the surface," Barclay said.

The next step, Barclay added, will be to look for Mercury-sized exoplanets at greater distances away from the host star Kepler 37. More planets could be orbiting the star and await discovery.

"We're looking at it very carefully," Barclay said. "There's nothing yet, but something may appear in the data."

Starlight tells the tale

Barclay and his team took great care to confirm the existence of planets around Kepler-37. The researchers knew that a dip in the star's brightness identified by the Kepler spacecraft could have come from several factors, most notably another star passing in front of the Kepler-37 target. So they ran a computer simulation to see if the newfound planet candidates could be false positives.

Using a tool called Blender from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, the researchers simulated several false positive scenarios in order to eliminate them. The results made researchers more than 99 percent confident that the planet candidates are actual planets, Barclay said.

The science team managed to obtain a close approximation of the size of the Kepler-37 star, in addition to spotting its planetary retinue.

The star's quiescent nature allowed the researchers to measure it with astroseismology, a technique that uses acoustic oscillations on the star's surface similar to how researchers probe the Earth's interior with seismic devices during earthquakes.

The uncertainty for a star's size is typically 20 to 30 percent, Barclay said. In this case, using astroseismology, the researchers narrowed the uncertainty to 3 percent.

Measurements showed Kepler-37 is about 75 percent the size of Earth's sun and 80 percent as massive. This places the star within the same "class" of stars as our sun.

The $600 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009, and has found more than 2,740 candidate alien worlds so far. Just 114 of these potential planets have been confirmed by follow-up observations to date, but mission scientists estimate that more than 90 percent will end up being the real deal. The spacecraft searches for small dips in stars' light caused by orbiting planets that pass in front of them periodically, dimming their brightness.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.