Universe's Energetic Cosmic Fog Stumps Scientists

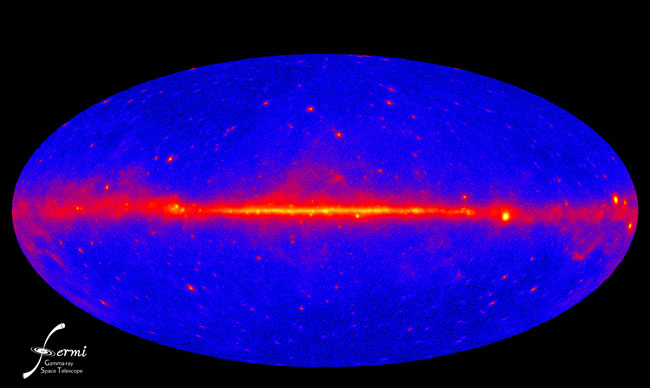

The ever-present fog of energetic gamma rays permeating theuniverse isn't created by what astronomers expected, new observations from NASA'sFermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope reveal, leaving scientists with a new cosmicmystery to solve.

The sky glows in gammarays even far away from well-known bright sources, such as pulsars and gasclouds within our own Milky Way galaxy or the most luminous active galaxies.Conventionally, astronomers thought that the accumulated glow of activegalactic nuclei ? black hole-powered jets emanating from active galaxies ?accounted for most of this gamma-ray background.

"Thanks to Fermi, we now know for certain that this isnot the case," said Marco Ajello, an astrophysicist at Kavli Institute forParticle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), jointly located at SLAC NationalAccelerator Laboratory and Stanford University in California.

For now the scientists are representing the unknown sourceswith a dragon symbol ? something that ancient mapmakers used to represent areasof the world not yet explored.

Ajello and other Fermi scientists used data from thetelescope's first year in action and compared the emission from active galaxiesthat Fermi detected directly against the number needed to produce the observedextragalactic background.

Active galaxies possess central black holes containingmillions to billions of times the sun's mass, known as supermassive black holes.As matter falls toward the black hole, some of it becomes redirected into jetsof particles traveling near the speed of light.

These particles can produce gamma rays in two differentways. When one strikes a photon of visible or infrared light, the photon cangain energy and become a gamma ray. If one of the jet's particles strikes thenucleus of a gas atom, the collision can briefly create a particle called apion, which then rapidly decays into a pair of gamma rays.?????

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But it turns out that active galactic nuclei are only minorcontributors to the background gamma ray glow.

"Active galaxies can explain less than 30 percent ofthe extragalactic gamma-ray background Fermi sees," Ajello said. "Thatleaves a lot of room for scientific discovery as we puzzle out what else may beresponsible."

Ajello presented his findings Tuesday at a meeting of theAmerican Astronomical Society's High-Energy Astrophysics Division in Waikoloa,Hawaii. A paper on the findings has been submitted to The AstrophysicalJournal.

What the mystery majority contributors are isn't yet known,though the team has a few ideas.

Particles accelerated both in star-forming galaxies andgalaxy cluster mergers could contribute to the gamma ray background, thescientists said.

And darkmatter ? the mysterious substance that neither produces nor obscures lightbut whose gravity corrals normal matter ? is always a possibility.

"Dark matter may be a type of as-yet-unknown subatomicparticle. If that's true, dark matter particles may interact with each other ina way that produces gamma rays," Ajello added.

Improved analysis and extra sky exposure will enable theFermi team to address these potential contributions.

But what the unknown source turns out to be isn't theimportant part of the finding, said Martin Weisskopf, Chandra Project Scientistfrom NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center who isn't involved with the Fermiteam. What matters is that "there is apparently a population of gamma raysources out there that one cannot identify," he said.

Launched in June 2008, the Fermispace telescope is continuously mapping the sky in gamma ray wavelengthsand looking for so-called gamma ray bursts, the brightest explosions in theuniverse.

- TheStrangest Things in Space

- TheFermi Gamma-Ray Telescope Part 1, Part2

- BestView Ever of Universe's Most Extreme Energy

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.