Jupiter's Great Red Spot Is Shrinking

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

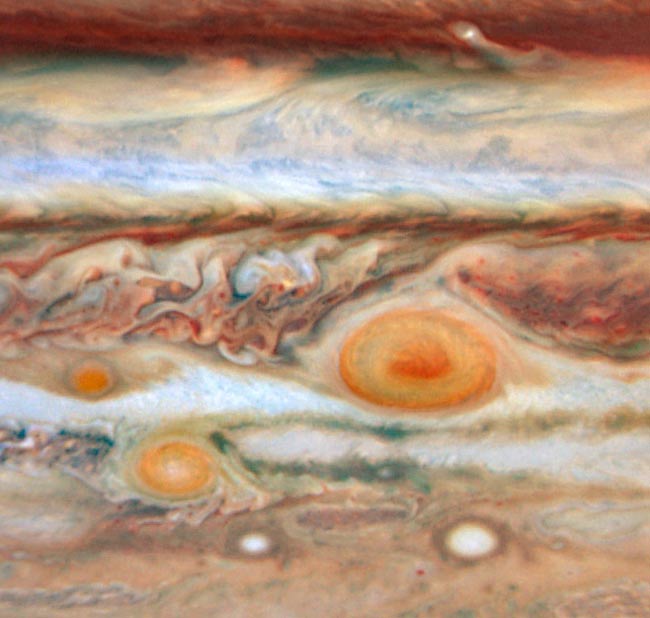

On Earth, hurricanes form and dissipate in a matter of days. On Jupiter, storms can rage for years or even centuries. The Great Red Spot, a colossal storm twice the diameter of our planet, has lasted at least 300 years.

But now that mother of all storms is shrinking just as other spots emerge to challenge its status.

Observations of cloud cover over the past decade or so have suggested the huge, oval tempest was getting smaller as Jupiter's climate changes. But such observations are tricky because it's hard to find the edges of the storm compared with nearby clouds on the visible surface of a gas planet that is entirely shrouded in colorful clouds. Nearby storms can nip off parts of the giant storm, and in turn the Great Red Spot can consume nearby clouds.

However, wind velocity data collected from 1996 to 2006 has allowed scientists to size up the storm more accurately by analyzing wind speeds and directions.

"The velocity data show that the Red Spot has been shrinking along its major diameter by about 15 percent over that period," said Xylar Asay-Davis, who conducted the study along with Phil Marcus, Mike Wong and Imke de Pader at the University of California at Berkeley.

Not dying

The finding agrees with other studies of cloud cover, Asay-Davis said, and it puts the conclusion on more solid footing. "Velocity is a more robust measurement because the clouds associated with the Red Spot are also strongly influenced by numerous other phenomena in the surrounding atmosphere," he said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's not clear yet why the storm is shrinking, but after 300 years of hanging in there, the spot is in no danger of disappearing anytime soon, Asay-Davis said. It continues to kick up winds that routinely exceed 300 mph.

"We find that the Red Spot has been shrinking but not slowing down," Asay-Davis told SPACE.com.

There is a balance of energy flowing in and out of the storm, either as it mixes with the surrounding atmosphere, consumes smaller storms, or when energy is radiated into space, he explained.

"We don't fully understand all the sources of energy, or the ways the Red Spot loses energy, but these can become slightly imbalanced for a period of time, and this is likely to be what is causing the Red Spot to shrink -- less energy is being fed in and more is slowly dissipating away," he said.

Asay-Davis and colleagues have used images from the Cassini spacecraft from the year 2000 to construct the highest resolution "velocity map" to date, showing wind speed over the whole planet between -70 and 70 degrees latitude. Gusts on Jupiter typically reach 250 mph. The research was presented in November at a meeting of the American Physical Society fluid dynamics division.

Climate change

The ongoing research aims to grasp Jupiter's overall, complex and changing climate.

The giant planet underwent a major upheaval from 2005 to 2007 when "a bunch of unusual weather patterns and color changes occurred all over the planet," Asay-Davis said.

The changes spawned the Little Red Spot in 2006, a plucky storm whose size and speed could eventually rival its big brother, other scientists say.

"In terms of maximum wind speed, the Little Red Spot as measured in 2007 and the Great Red Spot when last measured in 2000 are just about the same," Andrew Cheng, a physicist at Johns Hopkins University said last May.

The Great Red Spot may not go away, but its status could be challenged.

"The Great Red Spot may not always be the largest and strongest storm on Jupiter," said Glenn Orton, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

What's going on

Back in 2004, Marcus, a mechanical engineer at Berkeley, predicted that in 2006 or so, climate changes in Jupiter's southern hemisphere would destabilize jet streams and spawn new storms.

"We think that upheavals might be related to the way that vortices move heat around the planet -- when there are many vortices, they are very efficient at moving heat all the way from the equator to the poles," Asay-Davis explained. "But when there are fewer, they are likely to be much less efficient."

Back in 1998 to 2000, three large storms, all white ovals, merged. That might have had a big impact on the entire planet's climate.

"The south pole may be getting colder, while the equator gets a bit warmer," Asay-Davis said. "The recent upheaval may have been Jupiter's way of adjusting or compensating for this climate change. Eventually, we may see new vortices form that will mix up the heat again. We hope that we can continue to produce wind field maps of Jupiter so as to keep monitoring the climate in the years and decades to come."

- Video: Say Goodbye to Venus

- The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy

- Image Gallery: Jupiter's Moons

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.