Volcanic Activity Possible on Object Beyond Neptune

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

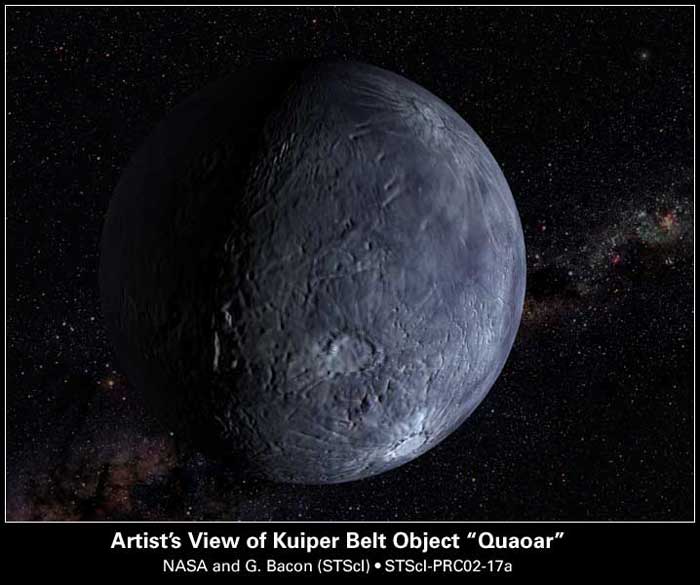

A large planet-like object out in the realm of Pluto shows signs of either a relatively recent collision or perhaps volcanic activity, astronomers said today.

If proven out, it would be the first known volcano on an object other than a planet or moon.

Earth and Mars both have volcanoes, and Jupiter's moon Io is a riot of volcanic activity.

Something's going on

Quaoar, as it is known, resides in the Kuiper Belt, a region of icy objects beyond Neptune's orbit. Astronomers expect most Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) to be relatively pristine leftovers from the formation of the solar system. They are the comets that have not yet made a close pass around, the wannabe planets that never grew quite big enough.

Quaoar (pronounced kwa-whar) is roughly 783 miles (1,260 kilometers) wide, second only in size among KBOs to Pluto, with a diameter of 1,490 miles (2,400 kilometers).

KBOs are thought to be composed of rock, water ice and various other frozen chemicals. Hundreds have been found, but most are too far away and too small to study in detail. Water ice has been detected on a few.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study, led by David Jewitt of the University of Hawaii's Institute for Astronomy, is reported in the Dec. 9 issue of the journal Nature.

Jewitt and a colleague found signs of ammonia hydrate and crystalline water ice on the surface of Quaoar. Both substances should be destroyed over a few million years by particle irradiation, they say. That's a short period of time considering the solar system's entire life of 4.6 billion years.

"We conclude that Quaoar has been recently resurfaced, either by impact exposure of previously buried ices or by cryovolcanic outgassing, or by a combination of these processes," the scientists conclude.

Surprise finding

The conclusion is not firm, but intriguing nonetheless. Being so far from the Sun, KBOs should not be warm enough to form crystalline ice without some sort of unusual circumstance.

Water ice incorporated into an object at low temperatures ought to be amorphous, rather than having the "highly coordinated architecture of a crystal lattice," explains Caltech scientist David Stevenson. Based on lab work, scientists think water must be heated to about minus 279.7 Fahrenheit (100 Kelvin) in order to form crystalline ice.

The frigid space of the Kuiper Belt, billions of miles from the Sun, is even colder than that.

"The presence of crystalline ice is surprising," said Stevenson, who was not involved in the new study but wrote a review of it for the journal.

"The precise temperature required, however, is not known and may not be the same in laboratory experiments as it is in space," Stevenson cautions. "Yet it might be that we are seeing evidence for 'planetary' processes such as volcanism within these bodies."

More study needed

The crystalline ice was confirmed recently in separate research done by the discoverers of Quaoar, Stevenson said.

The claim of ammonia hydrate is less convincing, Stevenson writes, but he notes that based on theory, Quaoar ought to have some ammonia inside. He said a mixture of ice and ammonia deep in the interior would be less dense than the rest of the object.

"It could percolate upwards and perhaps segregate to form a fluid-filled crack," which might propagate to the surface, or near to it," he said. "All of these processes are directly analogous to basaltic volcanism on Earth and other terrestrial planets."

Stevenson stresses that this scenario is speculative, and that more observations are needed.

- The Discovery of Quaoar

- New View of the Outer Solar System

- Io, the Most Volcanic Body in the Solar System

- Planet Building: Volcanoes No Longer Rule, But They Still Rage

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.