Mystery of Strange Star Outbursts May Be Solved

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Scientists have detected what appears to be a stellar outburst from a pair of stars locked in a cosmic tryst within a shared veil of gas, a find that marks the first discovery of a long-sought type of space eruption.

Most outbursts from stars are lumped into two categories — novas or supernovas. A nova is a thermonuclear explosion from a white dwarfstar driven by fuel piled on from a companion star. Novas do not result in the destruction of their stars, but supernovas do.

Supernovas, which are bright enough to briefly outshine all the stars in their galaxies, happen in two known ways — type Ia supernovas occur after a white dwarf dies from gorging on too much fuel from a companion star, while type II supernovas take place after the core of a star runs out of fuel, collapses into an extraordinarily dense nugget in a fraction of a second, and then bounces and blasts outward.

However, over the years, scientists have recognized another class of outbursts that are brighter than novas but dimmer than supernovas. Investigators called these mysterious events intermediate-luminosity red transients, or ILRTs. [Top 10 Star Mysteries]

Now, researchers suggest the culprits behind these enigmas may lurk behind shrouds of gas.

"I find it extremely exciting that we have explained a class of events that previously no one knew what they were," study lead author Natasha Ivanova, an astrophysicist at the University of Alberta in Canada, told SPACE.com. "That does not happen very often in science."

Two stars in dusty veil

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

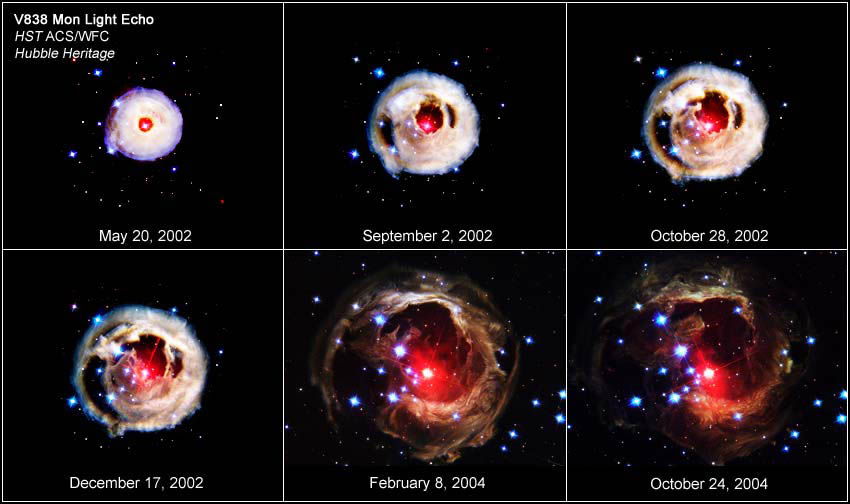

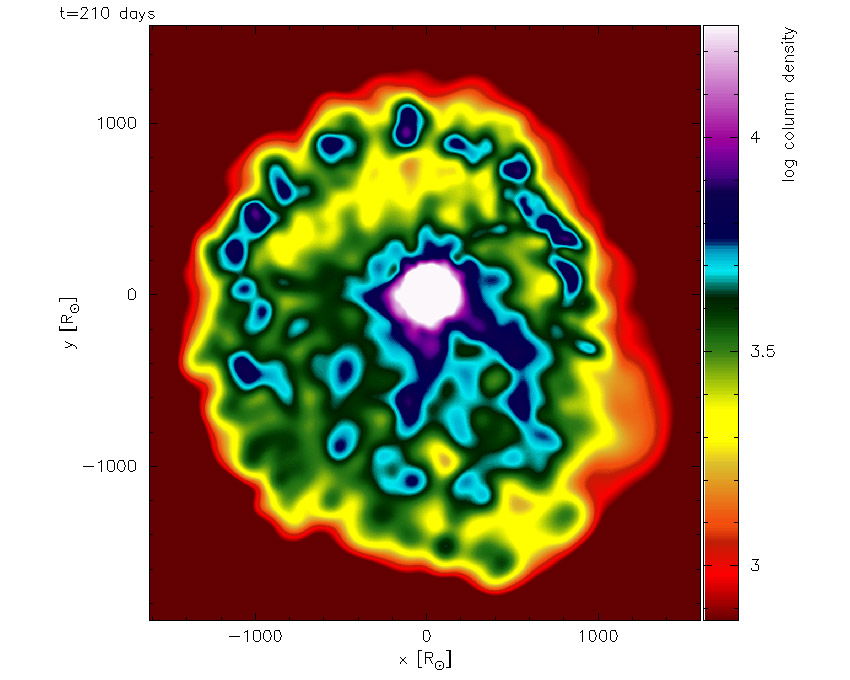

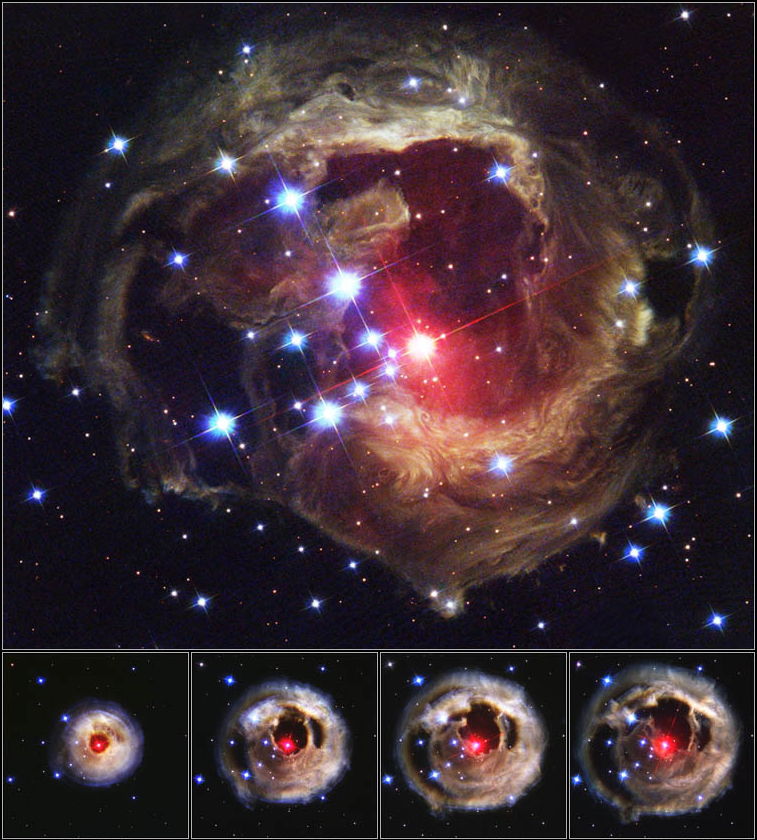

Scientists had long theorized that two stars can temporarily orbit each other with an envelope of gas they share. In these "common-envelope events," the star with less mass should become engulfed by matter from the larger companion star. The interactions between these stars can explosively hurl this super-hot envelope away from them at speeds of up to 2.2 million mph (3.6 million kph), releasing about as much mass as a supernova and about 10,000 times more than a nova.

However, astronomers did not expect to see these events directly. They are both rarer than novas but not as bright as supernovas, making them difficult to spot.

After developing computer models of the properties of common-envelope events, researchers found the energies, colors, short time scales, ejection velocities of ILRTs, as well as the rates at which they happened, match those of the predicted properties of long-sought common-envelope events.

"The surprise was that the appearance of the events (common-envelope events) is very different to what the original predictions were — the outbursts are much brighter and the durations are much longer than once thought," Ivanova said.

New star outburst model

This new model applies best to a subset of ILRTs often called luminous red novae. "It may be expected that not all of the ILRTs must necessarily be caused by common-envelope events, and some don't seem to be easily explained by our model unless it will be extended to take into account further complications," Ivanova said.

Common-envelope events are thought to create many binary systems, and could potentially help produce the progenitors of type Ia supernovas and gamma-ray bursts, the most powerful explosions in the universe. The scientists estimate about 24 common-envelope events happen every 1,000 years per galaxy like the Milky Way.

"We hope that the whole field of studies of interacting binaries — this includes such binaries as Type Ia progenitors, gamma-ray burst progenitors and merging double-stellar black holes — will receive a strong shake up," Ivanova said.

Ivanova and her colleagues detailed their findings in the Jan. 25 issue of the journal Science.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us