Most Massive Galaxy Cluster of Early Universe Discovered

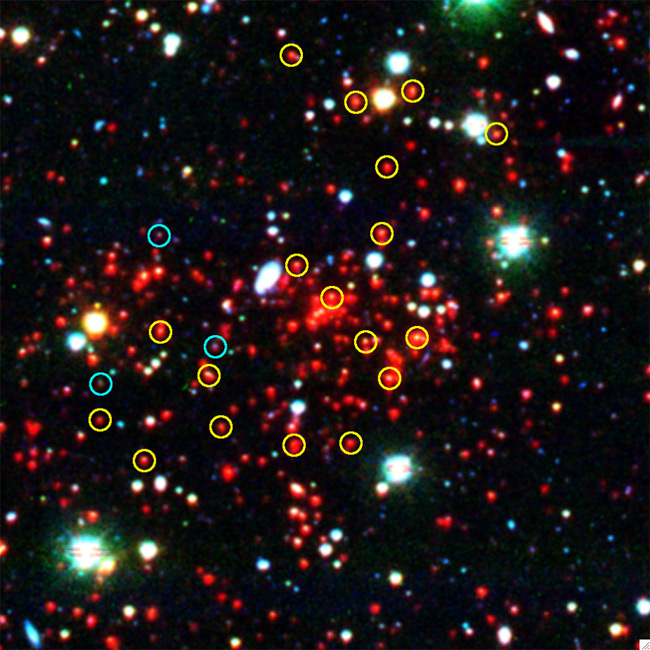

The most massive conglomeration of galaxies ever spotted inthe early universe has been found, astronomers say.

This behemoth galaxy cluster contains about 800 trillion sunspacked inside hundreds of galaxies. And it's not even finished growing.

The newfound cluster, called SPT-CL J0546-5345, is about 7billion light-years from Earth, meaning that its light has taken that long toreach us. Thus, astronomers are seeing this clump as it was 7 billion yearsago.

By now, it likely will have quadrupled in size, researcherssaid. The universe is about 13.7 billion years old. [Photo of the new galaxycluster]

"This galaxycluster wins the heavyweight title," astronomer Mark Brodwin of the Harvard-SmithsonianCenter for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., said in a statement. "It'samong the most massive clusters ever found at this distance."

While there are some heavier clusters in the near universe,if we could see this cluster as it is today, it would likely rank among themost massive clusters of all, the researchers said.

Brodwin and colleagues reported the discovery in a recent editionof the Astrophysical Journal.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dark energy

The discovery could help scientists piece together the earlyhistory of our universe, as well as how strange stuff called darkenergy played a role.

Seven billion years ago, our solar system ? which is about4.5 billion years old ? was not yet born. This cluster must have formedrelatively soon after the Big Bang to have amassed such a girth so early,scientists said.

"This cluster is full of 'old' galaxies, meaning thatit had to come together very early in the universe's history ? within the first2 billion years," Brodwin said.

These days, new galaxy clusters cannot form because of theuniverse's accelerating rate of expansion ? each galaxy is flying apart fromall others at ever-increasing speeds. This is thought to be caused by amysterious force scientists have named dark energy.

Scientists think dark energy is behind the universe'smysteriously accelerating expansion, but they can't establish for sure thatthis force exists.

Weighing massive clusters like SPT-CL J0546-5345 could helpastrophysicists ?pin down the nature of this odd quantity.

South Pole vision

The galaxy cluster was spotted by a new, huge 33-foot(10-meter) telescope at the South Pole, where the observatory benefits from an exceptionallyclear, dry and stable atmosphere that enables extremely crisp high-resolutionphotos.

The so-called SouthPole Telescope, funded by the National Science Foundation and run byscientists at more than a dozen international institutions, is finishing up itsfirst survey of a huge swath of the sky in relatively long-wavelength,low-frequency submillimeter light.

Once the survey is complete, the researchers hope to findmany more previously unknown giant galaxy clusters.

"After many years of effort, these early successes arevery exciting," Brodwin said. "The full SPT survey, to be completednext year, will rewrite the book on the most massive clusters in the earlyuniverse."

- What Is Dark Energy?

- You Decide: What's the Greatest Mystery in Science?

- Video: The Biggest Cosmic Collisions

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.