Mystery Spirals on Mars Finally Explained

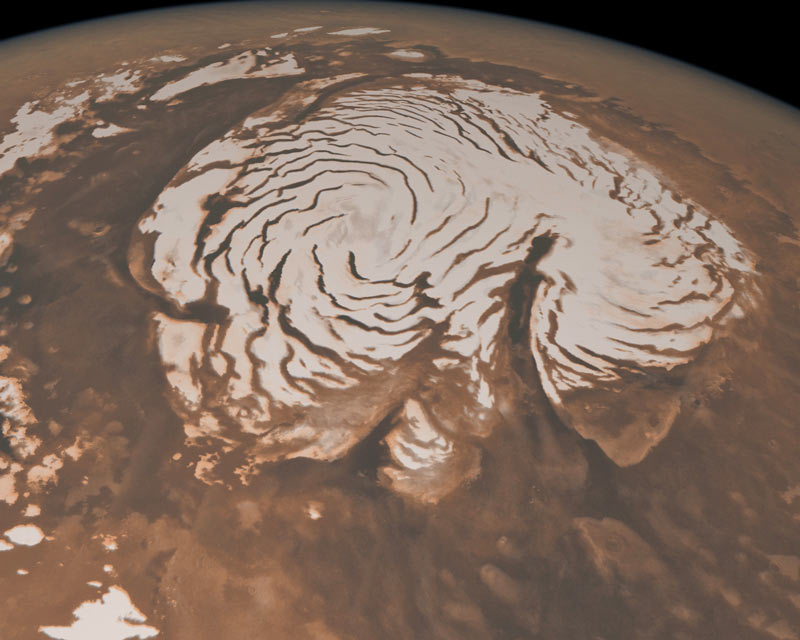

Huge troughs curving outward from the north pole of Marslike the arms of a pinwheel were not carved into the polar ice caps by somemysterious force, researchers have discovered. Instead, the shifting patternarose from a long process of formation and erosion that gave it the appearanceof slowly moving and spiraling inward over time.

A similarly snail-like process gave rise to the ChasmaBoreale canyon that cuts into the side of the giant pinwheel pattern, known asthe north polar layered deposits (NPLD). The unveiling of the origins of thecanyon and NPLD came courtesy of ground-penetrating radar carried by twoMars orbiters.

Scientists had previously favored the idea that a naturalforce recently carved both the canyon and pinwheel pattern into older geologicaldeposits. But they could not test their theories beyond what they could see onthe Martian surface, as if trying to judge a book by its cover.

"Radar is like opening the book; we can read each pagenow," said Isaac Smith, a planetary scientist at the University of TexasAustin. "People were looking at the outside and thinking they knew whatthe book was about, but they didn?t."

Such technology allowed scientiststo take 2-D cross-section images of the troughs and reveal the layers withinthe walls, like snapshots in time going back through the red planet's history.Radar also helped trace reflective markers that followed the geometry ofunderground structures to build up a 3-D sense of the layers.

The radar studies do not answer the riddle of what changesin the Martian atmosphere spurred the formation of both the canyon and theyounger spiraling troughs. But they do give scientists a new understanding ofthe timing of the processes that allow the wind and sun to shape the Martiansurface over a certain period, and that may lead to more evidence-based climatemodels for the red planet.

Not built in a day

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Chasma Boreale appearsto cut into the side of the ice-richpolar layered deposits which sprawl across 621 miles (1000 kilometers) and areabout 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) thick. But the radar studies showed that themassive canyon formed long before the appearance of the shallower troughs whichmake up the spiraling arms.

Some researchers had suggested that pressure-induced meltingor sub-ice volcanic activity caused the canyon to appear. Yet the canyon'sbirth turned out to result more from the slow workings of climate and time,rather than rapid or catastrophic forces.

"There were many hypotheses about the Chasma Boreale,and all assumed it was a recent feature cut into the polar ice," said JackHolt, a geophysicist at the University of Texas, Austin. "But now we knowit's an old feature, and you can interpret the stratigraphy in thatcontext."

Holt led the radar study on the Chasma Boreale, while hiscolleague Smith focused on the spiral troughs. Their two studies appear in theMay 27 issue of the journal Nature.

Both the Chasma Boreale and the younger troughs formed ontop of an older polar ice cap. Layers of water-ice and grit began depositing,and soon an early form of the canyon appeared. But it wasn't alone; asimilarly-sized canyon also began to take shape.

Then something in the Martian climate caused the deposits tostop. Erosion then took over, as the wind wore at the surface and the suncaused some ice to sublimate and turn directly into vapor. There was noevidence of water melt from the radar studies, Holt told SPACE.com.

Eventually the layers began depositing again on top of oneanother, and one of the canyons ended up getting filled in. But natural forcessuch as the wind somehow spared the Chasma Boreale by preventing deposits fromfilling it, and helped preserve the canyon that today stretches 311 miles (500kilometers) long and 62 miles (100 kilometers) wide.

"The [canyon formation] happened for some time with nogood age constraints," Holt said. "That was about 75 percent of theway through the history of this, but then the troughs started forming. We don'tknow why."

Picking up good migrations

The younger, shallower troughs began to form sometimebetween 2.49 million years and 467,000 years ago. They represented depressionson top of about three quarters of built-up polar layered deposits, but theydidn't just sit still.

Instead, a combination of wind and perhaps sun erosion beganto wear away at the southern, equator-facing sides of the polar layereddeposits. Wind then carried a trickle of eroded material to the northern, polar-facingsides of the deposits.

As a result, the troughs appeared to slowly spiral inward asthey crept northward toward the pole. That appearance of movement has strongresemblance to how sand dunes seem to move over time, Smith said.

"Radar shows that three quarters of the ice has beensitting there, but the surface was altered by wind," Smith explained."Some troughs have moved as much as 65 kilometers [40 miles], and manymoved much less."

More material also accumulates on top of the deposits as thespiral pattern tightens, Holt said. That means the deposits get thicker andhigher all the time.

More climate mysteries

Understanding how the north polarice cap patterns appeared may also help scientists understand the globalclimate of Mars. Holt and Smith hope to continue examining the patterns ofaccumulation and try to understand why snow or frost built up unevenly tocreate the polar layered deposits.

"That tells us a storyabout the wind and possibly the sun," Smith said. "That's thecontinuing story."

Researchers can plug their evolvedunderstanding of the natural forces into Mars climate models to make the modelsmore realistic. And better models might help reconstruct how water icetransfers between the poles and the mid or lower latitudes of the red planet,through sublimation and frost or snow.

"You can then start placing age constraints on icedeposits at lower to mid latitudes, which are more accessible to robotand human missions," Holt pointed out.

Future work might also solve the mystery of the south polarlayered deposits, which also resemble the spiral pattern of their north polarcousins. But unlike in the north, the south polar layered deposits don't appearto move.

Smith speculated that a colder climate and higher elevationat the south polar ice cap may translate into stickier frozen material andweaker winds. Holt also noted that the southern region appears older, so thatperhaps the climate simply did not allow for movement during the time in whichthe deposits formed.

What lies beneath

Part of the reason that the southern polar ice cap remainsmore mysterious is that radar does not work as well in that region. Reflectivemarkers or structures beneath the north polar layered deposits helped the radarstudies trace the geometry and layers underground, but such markers appear lesscommon in the south.

Still, Holt and Smith praised the radar carried by the Marsorbiters as the crucial components that solved at least the origins of the northpolar layered deposits. Such equipment has been used in Antarctica since the1970s, but did not fly out to Mars until the past decade.

The Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and IonosphericSounding (MARSIS) on the Mars Express orbiter can probe deep beneath thesurface with less resolution, while the Mars ReconnaissanceOrbiter?s SHAllow RADar (SHARAD) has both higher frequency and bandwidthwith shallower penetration that can still examine the underground layers andstructure of the polar layered deposits.

Such powerful tools could begin tomake a case for flying even better radar out to Mars someday.

"In the future, we could probably learn even more aboutthe subsurface," Holt said. "There's still more we could learn with anewer, better radar."

- Images: Red Planet Revealed

- Get to Know MRO: 10 Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Facts

- Gallery: Ice on Mars

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.