Milky Way's Giant Black Hole Probed Like Never Before

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

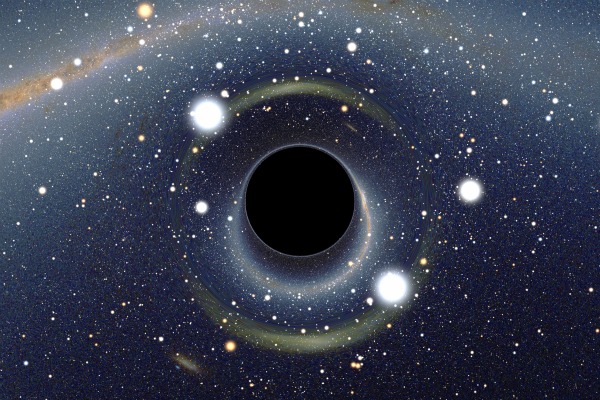

The gigantic black hole at the heart of our Milky Way galaxy is coming into sharper focus.

For the first time ever, astronomers have detected magnetic fields just outside the event horizon — the "point of no return" beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape — of the Milky Way's central supermassive black hole, which is known as Sagittarius A*.

"These magnetic fields have been predicted to exist, but no one has seen them before," study co-author Shep Doeleman, assistant director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Haystack Observatory, said in a statement. "Our data puts decades of theoretical work on solid observational ground." [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

Supermassive black holes lurk at the core of most, if not all, galaxies. Sagittarius A*, which lies about 25,000 light-years from Earth, is about 4 million times more massive than the sun, but its event horizon is just 8 million miles (12.9 million kilometers) wide — less than the average distance from Mercury to the sun.

The scientists studied Sagittarius A* using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a system of radio dishes around the world that are linked up to form one enormous instrument sensitive enough to resolve features as small as 15 micro-arcseconds — the equivalent of spotting a golf ball on the moon, study team members said.

The EHT detected polarized light emitted by electrons zipping around Sagittarius A*, which allowed the researchers to trace out the structure of the black hole's magnetic field. The observations show that this magnetic field is chaotic in some regions and much more orderly in others, including the areas where powerful jets are generated, the researchers said. (Magnetic fields are thought to power these jets, which can blast material through space for thousands of light-years.)

In addition, the EHT data revealed that the supermassive black hole's magnetic field is incredibly variable, shifting markedly every 15 minutes or so.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Once again, the galactic center is proving to be a more dynamic place than we might have guessed," study lead author Michael Johnson, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in the same statement. "Those magnetic fields are dancing all over the place."

The researchers reported their results online today (Dec. 3) in the journal Science.

The new study could help researchers better understand black holes, light-gobbling monsters that nonetheless blast out incredibly powerful radiation as gas and dust spiral into their insatiable maws, team members said.

"With this result, the EHT team is one step closer to solving a central paradox in astronomy: Why are black holes so bright?" Doeleman said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.