Asteroid Near Neptune Found in Gravitational Dead Zone

Astronomers have discovered a new asteroid in a region of Neptune's orbit where no previous object was known to exist -- a so-called gravitational "dead zone."

The asteroid, which follows Neptune's orbit around the sun, may help shed light on fundamental questions about planetary formation and migration.

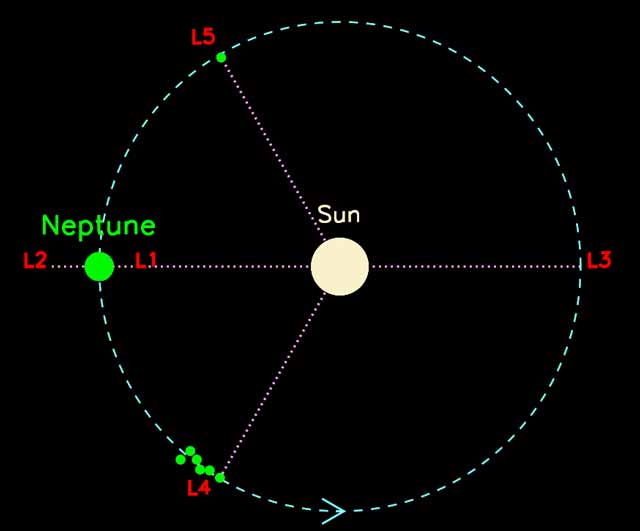

The asteroid, classified as a Trojan, was found in a difficult-to-detect area near Neptune, known as the Lagrangian point L5. Lagrangian points are five areas in space where the gravitational tugs from two relatively massive bodies -- such as Neptune and the sun -- balance out. This allows smaller bodies, like asteroids, to remain stable and fixed in synch with the planet's orbit, as they orbit the sun.

Trojan asteroids, named after the famous war in Greek mythology that was waged by the ancient Greeks against the city of Troy, share a planet's orbit around the sun, but do not collide with it because they remain safely near the Lagrangian regions.

Trojan asteroids have previously been found in some of the stable points near Neptune and Jupiter, but this is the first discovery of a Trojan in Neptune's L5 region.

"We believe Neptune Trojans outnumber the Jupiter Trojans and the main-belt asteroids between Mars and Jupiter," Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C., told SPACE.com. "If Neptune was where the main-belt was, we'd know thousands of these objects."

He added that thousands of Trojan asteroids are associated with Jupiter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stable regions

At Neptune, the L4 and L5 regions are 60 degrees along the planet’s 360-degree orbital path, ahead and behind the planet respectively. In this configuration, dust grains and other small bodies are able to collect and remain there.

Neptune Trojans are very faint because they are so far away from the Earth and the sun, making them difficult to detect. Astronomers Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C., and Chad Trujillo of the Gemini Observatory in Hilo, Hawaii, discovered the Trojan asteroid, 2008 LC18, through an innovative observational strategy.

Using images from the digitized all-sky survey, the astronomers identified pockets of space in the stable regions where dust clouds in our galaxy blocked out the background starlight that crowds the galaxy's plane. This gave the researchers an observational window to observe asteroids in the foreground.

The L5 Neptune Trojan was found using the 8.2-meter Japanese Subaru Telescope in Hawaii. They then used the Carnegie 6.5 meter Magellan Telescope to observe and determine the object's orbit.

Sheppard and Trujillo had previously discovered three of the six known Neptune Trojans in the L4 region in the last several years. The L5 region is much more difficult to observe.

"You're looking at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, so there are a lot of stars and dust clouds there" [in the background], Sheppard told SPACE.com.

The astronomers' discovery proves that at least one Trojan asteroid exists in the L5 region of Neptune. And while the asteroid is too faint to be able to determine its composition, Sheppard and Trujillo were able to gather other details about the mysterious object.

"We estimate that the new Neptune Trojan has a diameter of about 62 miles (100 km), and that there are about 150 Neptune Trojans of similar size at L5," Sheppard said. "It matches the population estimates for the L4 Neptune stability regions."

A window to the past

The 2008 LC18 Trojan asteroid always trails behind Neptune and takes the same amount of time to circle the sun as the gas giant planet, but there is one key difference between the orbits of the objects, Sheppard said.

The asteroid has a highly inclined orbit, meaning for half of its orbit the asteroid swings north of Neptune and for the other half it sits south relative to the plane of the solar system. Even though it swings above and below this plane, the angle between the asteroid and Neptune relative to the sun remains at 60 degrees.

This is similar to several asteroids found in the L4 region, which suggests that the objects were captured into these stable regions in the early years of the solar system.

During this time, Neptune was moving on a different orbit than it is now, said Sheppard.

"This is a high-inclination object, as it would be if Neptune was on a much more eccentric orbit in the past," Sheppard said. "This supports the idea that the solar system was much more chaotic, and that giant planets didn't form where they are now, but migrated there."

Planets likely captured Trojan asteroids through a slow, smooth process of planetary migration, or, as giant planets like Neptune and Jupiter settled into their obits, their gravitational attraction may have trapped these objects in their current locations.

"In the distant past, Neptune likely migrated out several AU (astronomical units) and had a much more eccentric and chaotic orbit than it has now," Sheppard said.

The research from this study will be published in the Aug. 13 issue of the journal Science.

- Images - Asteroids Up Close

- 5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids

- NASA's New Asteroid Mission Could Save the Planet

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.