Noah's Cosmic Ark: Preserving DNA on the Moon

The complexity of life took billions of years to push and stretch and reshape the biological niche that is Earth. It would seem prudent - if one had the means - to save some portion of the blueprints of this majesty, so that the process would not have to start over from scratch in the event of a global cataclysm.

Morbid, for sure, yet still prudent. But where to put this valuable backup so that it is both safe and handy? And what form should it take?

Last week the head of Europe's lunar missions said a DNA library might belong on the Moon.

"It would act as a mini Noah's Ark for repopulating the Earth after a catastrophe," explained Bernard Foing, chief scientist with the European Space Agency, in a telephone interview with SPACE.com. "It would be a second chance."

The notion echoes one that has been slowly developing over the past few years in the United States. The Alliance to Rescue Civilization (ARC) advocates a "lunar sanctuary" to preserve Earth's whole record in case the planet is destroyed.

Interestingly, Foing had never heard of ARC, and ARC leaders did not know of Foing. The fact that the idea sprang up in separate intellectual circles may boost interest in the plan.

"It's wonderful," said Bill Burrows on learning of Foing's comments. "The more the merrier."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Burrows, who teaches journalism at New York University (NYU), said that he first heard of reseeding a decimated Earth from a lunar base in Robert Shapiro's 1999 book, Planetary Dreams: The Quest to Discover Life Beyond Earth. Burrows and Shapiro, a chemist at NYU, founded ARC to get the word out about planetary protection.

Global Killer

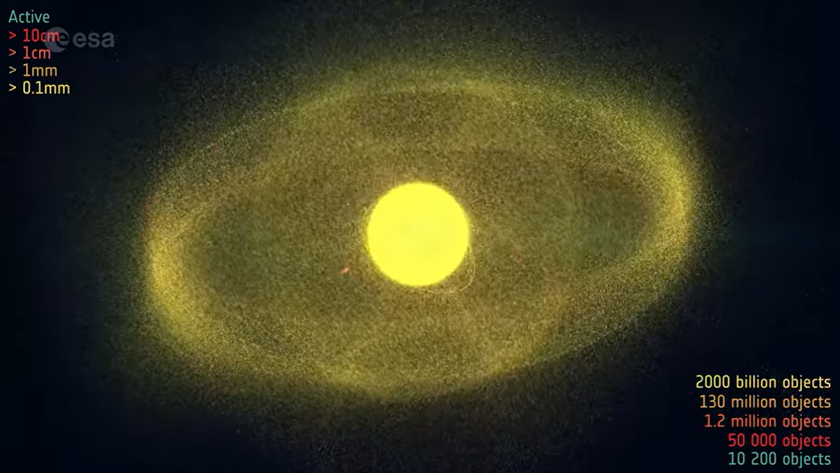

There are several known threats to life on Earth, and perhaps some that no one has yet imagined.

"Everybody tends to think of it in terms of a big dirty rock," Burrows said. Scientists estimate that a kilometer-sized boulder could cause planetary-wide devastation. There are hundreds of these large asteroids that astronomers are keeping an eye on. And a significant fraction of the estimated population of potentially deadly large asteroids -- those whose orbits cross in the vicinity of Earth's path around the Sun -- have yet to be found, other experts agree.

Burrows said there are "rogues" - asteroids outside the plane of the solar system - that are harder to spot.

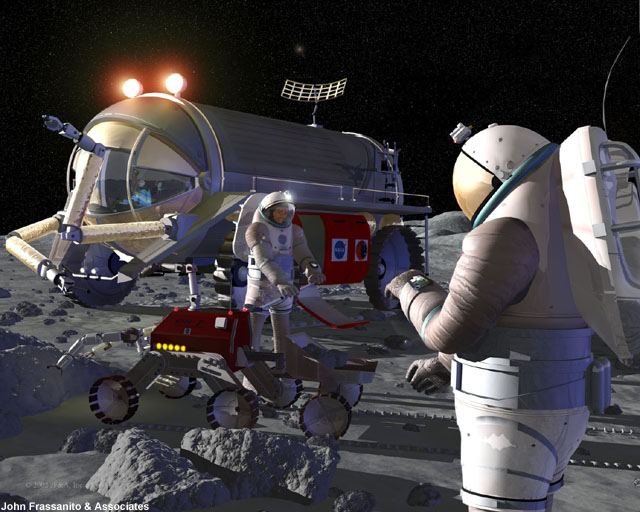

Besides the Armageddon that a large impact would unleash, there are nuclear wars and pandemic viruses to worry about. Foing, the European proponent of lunar living, believes there needs to be a self-sufficient colony on the Moon that can wait for the fallout of the disaster to subside. "It would need to be able to survive independent of Earth for many years," he said.

Foing thinks that a biosphere on the Moon would be the primary function of a lunar base, and only then could a DNA library be worth contemplating.

Burrows agreed: "You need to have people [on the Moon] to rescue Earth."

Storage and Retrieval

But the details of this rescue have yet to be worked out.

"The classic Noah's Ark would be living species," said Foing.

But keeping a zoo on the Moon that represents the diversity of life is not exactly practical. Besides all the room necessary for whales and elephants, Foing admits that the partial gravity of the Moon may not be suitable for the development of many organisms.

The alternative would be a much-more compact archive of DNA that could be "downloaded" when necessary.

"A 'DNA library' could consist of actual DNA samples, which might last for many thousands of years if stored dry, in the cold, and protected from radiation," Robert Shapiro, the NYU chemist, told SPACE.com.

These samples would be in the form of cells or tissues. "They contain the DNA, but would be more useful than raw DNA for recreating an individual of the species," Shapiro said.

DNA banks of this sort are already being set up on Earth. One of them, called the Frozen Ark, is cataloguing species on the verge of extinction. "If you can save the DNA, it still exists for future generations of research," said Bill Holt from the Zoological Society of London, who sits on the Frozen Ark steering committee.

But Holt said that the prime motivation of Frozen Ark is not for regenerating species that have disappeared. He says an operation like that is at an "entirely different scale."

Say, for instance, the idea would be to clone new organisms from tissues or blood. Besides a DNA sample, Holt explained, you would like to have an unfertilized egg, or oocyte, from the same species. This ensures that the DNA to be cloned matches the mitochondria and other cellular machinery of the egg host. But gathering and storing oocytes (or embryos for that matter) is often more complicated than for other cells.

And even if you can obtain an embryo by some means, "you need to know the reproductive biology of that particular species," Holt said. There would essentially have to be a separate nursery on the lunar base for every type of organism.

50 by 50

Another complication is the fact that a species needs a certain amount of genetic diversity to be viable.

"You can't have just one or two DNA samples, but you need hundreds," Holt said. Biologists debate over the exact numbers, but Holt thinks 50 females and 50 males is a bare minimum to fill in the gene pool.

The task becomes even more daunting when one thinks of the thousands of species we would likely deem necessary on a resurrected Earth, each needing a hundred or so samples to be stored indefinitely. Although he has never considered a project of this magnitude, Holt estimates that storing a single species for future seeding could cost a million dollars if not more.

"This is much more complicated than a DNA bank," he said.

It would certainly be simpler if a genetic code saved in a computer could be used to recreate a living organism, but this is currently not feasible, expert say. And yet, Holt could not discount the possibility. "You can never predict what people will be able to do in the future," he said.

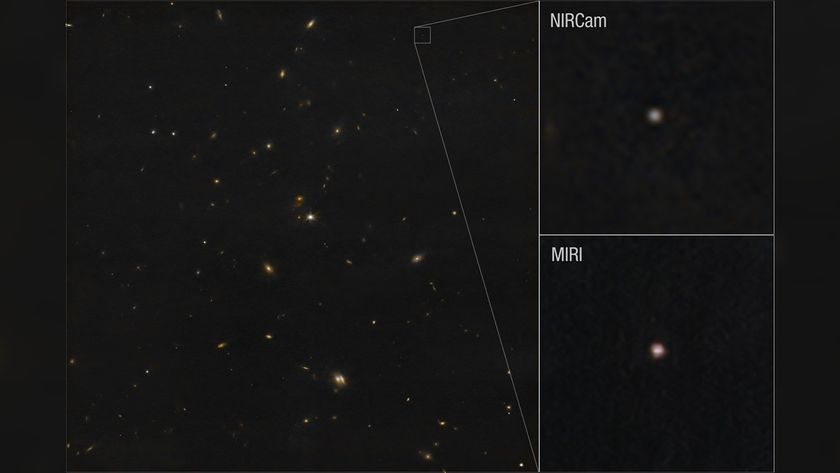

Regardless, Shapiro believes that it would be "prudent to store all of the DNA sequence data presently being collected by the Human Genome Project" safely on the Moon, "so that we never have to repeat it all, come what may."

Why the Moon?

Shapiro also emphasizes that there is more than DNA to be saved. Our cultural and scientific heritage is something we would hate to have to reproduce if calamity struck.

But would it not be easier to transfer this information to, say, a bunker deep underground?

Foing, who first raised the idea to a BBC reporter at the British Association Festival of Science last week, said this would defeat the purpose of having a self-sustaining support colony, since there would be no sunlight in a bunker for growing food. Burrows added that an underground archive would still be vulnerable to a large enough collision. He suggests that we do it on the Moon and on the Earth.

"The more you spread it out, the better," Burrows said.

Burrows does think it would be ridiculous to put an ark on Mars, where others hope to set up a colony. A rescue mission would take six months to a year from Mars, but only a few days from the Moon.

Foing notes that Mars may not be an entirely dead planet. "The Moon does not have any life, but at Mars we could end up erasing the indigenous life."

International Enterprise

Both Foing and the ARC proponents realize that backing up the planetary hard-drive is a long-term vision. "We're talking 100 years time scale," Foing said.

But they think the motivation in defending Earth might help focus all the other reasons to explore the Moon and beyond.

"This is the compelling reason to get off Earth," Burrows said.

Burrows is realistic, however, about the average citizen's interest in colonizing space. "Not all of Spain turned out to wave to Columbus," he said.

Burrows said the effort will require government backing, and he thinks it should be an international effort. The goal for ARC right now, though, is just to get people thinking about the future of space exploration and the fate of our planet.

"Our strategy is to write about it," Burrows said. And he has a new book coming out next year, "The Survival Imperative: Using Space to Protect Earth." He wants to make it clear to his readers that none of this will be easy. "Get Star Trek out of your head," he warned.

- More on the ARC project

- Top 3 Reasons to Colonize Space

- Top 10 Reasons to Inhabit Outer Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.