Hints of Unseen Moons in Saturn's Rings

A trio of new observations suggests several tiny, unseen moons orbit Saturn and control the shape of its rings.

One study found strong evidence for a small moon, likely just a few miles wide, creating patterns at the edge of a gap that are identical to features at another ring boundary generated by a larger, known moon.

In other research, scientists spotted clumps the size of football fields embedded in the rings. Nothing so small has ever been seen before around Saturn, but the one-dimensional images don't reveal whether the clumps are solid objects or cloud-like gatherings of particles. This work also revealed that Saturn's myriad ringlets have surprisingly sharp edges, suggesting they are sculpted by tiny, undiscovered moons.

A third investigation found a halo of oxygen around Saturn, which the researchers think is caused by constant collisions between small objects -- referred to as "moonlets" -- embedded in the rings.

The studies were presented last week at the annual American Astronomical Society Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Louisville, Kentucky.

Hiding in a gap

A few relatively small moons are clearly visible in major gaps between Saturn's rings and had been discovered in Voyager data. With diameters as little as 12 miles (20 kilometers), these moons are known to gravitationally shepherd ring particles as well as maintain gaps between the rings.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But whether or not every one of the dozen or so gaps in Saturn's rings have embedded moons is an important question the Cassini spacecraft is designed to answer. Scientists also do not know how Saturn's rings originally formed or exactly what they're made of.

Carolyn Porco of the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado led a study of Cassini images suggesting one possible new moonlet.

Porco told SPACE.com she has "circumstantial evidence" for a small moon in the Keeler gap, near the outer edge of Saturn's main rings. The evidence is in the form of "spiky wisps" of material that protrude into the Keeler gap from its outer edge.

The features resemble those generated on the inner edge of the F ring by the shepherding moon Prometheus, Porco said.

The moon has not been seen yet, and Porco suspects it's no bigger than about 3 miles (5 kilometers) or so in diameter. She stressed that the size estimate is just a guess, based on the size of the gap -- just 22 miles (35 kilometers) wide -- the dynamics involved, and the fact that the moon has never been seen.

"It was exiting to see the fingerprints of this moon," she said. "We'll be looking closely for it in future observations."

More moon fingerprints

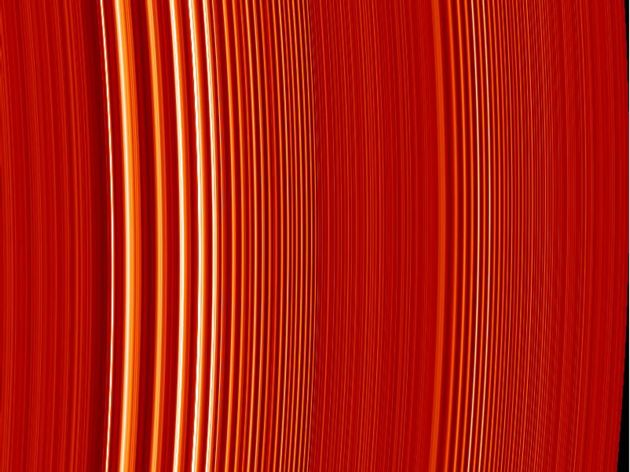

Another set of observations has helped scientists better understand the size of particles in the rings, also showing that the rings have stark cutoff points with glaring gaps between. This most detailed view ever obtained of Saturn's rings was made by watching light from a distant star flicker as it passed through the rings.

Particles are bunched very closely in individual ringlets, said Joshua Colwell of the University of Colorado at Boulder. At times, the starlight is completely blocked for stretches of 130 feet (40 meters). In other spots, the starlight shone right through. "We see rings go from completely transparent to completely opaque," Colwell said.

Future observations might reveal whether the structures are solid clumps -- essentially icy moonlets -- or fluffy agglomerations of particles that aren't stuck together.

What's potentially more telling is that the amount of material drops off to zero in as little as 160 feet (50 meters) from the edge of a ringlet.

"The very sharp transitions were not expected," Colwell said in a telephone interview.

It is likely that gravity from a nearby small moon, along with collisions between ring particles, confine the particles in a ringlet, he said.

The high-resolution observation also showed more than 30 density waves in the rings caused by gravitational interactions between moons and ring particles. Density waves have been spotted in the rings before, but not with this resolution.

"This can create a wave in the ring that looks like a ripple in a pond," Colwell said. "The shapes of these wave peaks and troughs help scientists understand whether the ring particles are hard and bouncy, like a golf ball, or soft and less bouncy, like a snowball."

Constant collisions

Another new set of observations shows an immense cloud of oxygen atoms surrounding Saturn.

Scientists think the cloud is replenished when moonlets within the ring system collide, shatter, and release ice particles. Radiation belts around the giant planet bathe the ice particles, which release the oxygen, said the University of Colorado's Larry Esposito, who heads up operation of Cassini's Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer.

The finding probably explains observations from earlier this year showing that ring particles are covered in gunk, and that the amount of gunk varies in different locations.

"The fluctuations we see can be explained by the recent destruction of small moons within the rings and by wave action in the rings that dredges fresh material onto the surfaces of the ring particles," Esposito said. "This indicates that the material in the rings is continually recycled from rings to moons and back."

Porco said the study of Saturn's rings and moons could pay off in an unexpected way.

The system is similar to the disk that is typically left orbiting a star after its formation, and out of which planets form. Determining how Saturn's moons and moonlets develop, collide, and sometimes end up in odd-shaped orbits could shed light on the formation of planetary systems.

- Cassini Full Coverage

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.