Is Mercury the Incredible Shrinking Planet? MESSENGER Spacecraft May Find Out

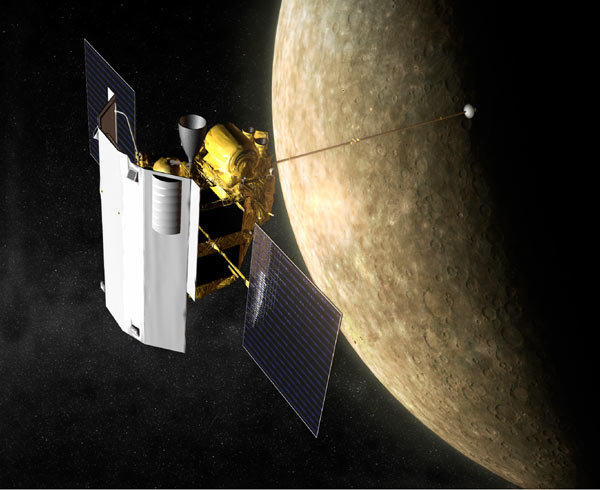

With a new spacecraft bound for Mercury, that tiny planet near the heart of the solar system, researchers are hoping to solve a slew of riddles about the small world.

Among the odder Mercurian attributes scientists hope to test is a theory that the planet is shrinking, contracting in on itself as its core slowly freezes.

"It's a pretty cool thing," said Mark Robinson, a Northwestern University researcher, of Mercury's slow contraction. "When I first heard it, I thought it was weird."

But the theory is based on images from NASA's Mariner 10 mission in the 1970s that show randomly strewn scarps across half of Mercury, where the surface appears to have buckled from within. Scientists hope that a new spacecraft -- MESSENGER -- will shed new light on both Mercury's surface as well as its metallic core.

Robinson, a science team member with the MESSENGER mission, said the spacecraft will give researchers a chance to look for signs of surface buckling on Mercury's hidden hemisphere, as well as collect surface composition data on material that may have once spewed out of the planet's interior.

The MESSENGER, or MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging, mission launched on Aug. 3 this year and is expected to reach Mercury in March of 2011. The spacecraft will make three successive passes around the planet before it finally enters orbit.

The incredible shrinking planet

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The idea that Mercury's surface was somehow shrinking arose when Mariner 10 returned images of great scarps biting deep into the planet's surface. One such scarp, Discovery Rupes, cuts a mile (1.6-kilometer) into Mercury's crust as it snakes across the surface.

On Earth, such scarps could resemble tectonic features like the fault lines running parallel to the coastal U.S., researchers said. But on Mercury, the formations are randomly distributed. The scarps also don't appear to have formed by the in-filling processes that led to similar features on Earth's moon due to their length, which can stretch hundreds of kilometers across the surface.

Under the shrinking surface theory, researchers believe that Mercury's crust first formed over a gigantic molten core. As that core cooled, it led to a volume change causing the surface to buckle and break.

Unlike water, which actually expands as it cools, most materials tend to contract and the same goes for Mercury's rocky crust, Robinson said. Based on observations of the planet's known hemisphere, scientists estimate the planet's surface has shrunk inward between less than one kilometer and three kilometers in all, he added.

"It's not something insignificant," Robinson said.

But since much of the mystery surrounding Mercury's surface stems from its poorly understood core, researchers have their work cut out for them.

"Our understanding [of the core] is very rudimentary," Robinson said. "It's just based on the fact that Mercury has this very high uncompressed density."

Because Mercury is extremely dense for its size -- it's comparable to Earth -- researchers believe it has a large metallic, most likely iron core. But exactly how large the core is, whether its outer regions are molten, and whether it rotates to power the planet's strong magnetic field, are still unknown.

"Mercury is a small enough planet that its core should have frozen about 2.2 billion years ago," said MESSENGER payload manager Robert Gold, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

Mercury is 3,031 miles (4,878 kilometers) in diameter, a bit larger than Earth's moon.

A better view with MESSENGER

MESSENGER should give scientists the view they need to at least strengthen their shrinking Mercury theory, if not confirm it outright.

Not only will the spacecraft spend an entire year mapping the entire planet, as opposed to the Mariner 10's 45 percent scan, it will also do so with unprecedented detail. The cameras onboard MESSENGER can resolve surface features down to just 60 feet across (18 meters) compared to the one-mile (1.6-kilometer) resolution offered by Mariner 10.

The spacecraft's Mercury Laser Altimeter instrument will track how the planet wobbles on its axis to help researchers determine the state of its core. Surface-scanning tools, meanwhile, will study the composition of ancient lava flows providing a window into Mercury's mantle.

"I would be very surprised if [Mercury's] unseen hemisphere has features we don't have hints about on the side we've seen," Robinson said.

This article is part of SPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.