Forget Big Asteroids: It's the Smaller Rocks That Sneak In and Blow Up

Put aside the vision of Bruce Willis wrestling with huge space rocks threatening to doom Earth "Armageddon"-style. It turns out that people should be more worried about smaller space rocks that explode in our atmosphere.

While smaller than Earth-busting asteroids, these "airbursters" ? like the space rock that exploded in 1908 high over Tunguska, Siberia ? are more immediate threats, scientists say. They can cause localized destruction and may intrude in our airspace with little warning time.

When an airbursting asteroid, called a bolide, exploded over an island region of Indonesia late last year, it rocked the residents' world with an estimated energy release of about 50 kilotons, equal to some 110,000 pounds of TNT.

Such objects are expected to impact the Earth on average every two to 12 years. [Brilliant Fireball Video]

Physics of airbursts

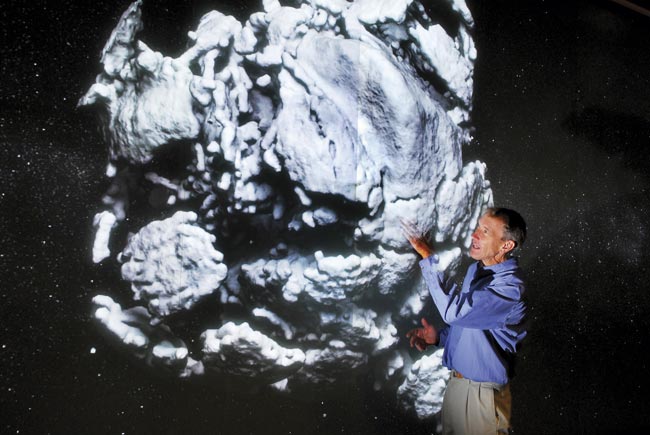

The risks of exploding asteroids and the need to keep watch for hazardous near-Earth objects took center stage at September's Space 2010 conference in California, ?sponsored by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

"We used to think that the only real threat was from impacts that hit the ground ? and that the atmosphere would protect us from the small ones,? said physicist Mark Boslough of Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, N.M. ?We never really thought about the physics of airbursts. ? There hasn't been that much research."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Given his modeling of airbursts, Boslough pointed out that smaller NEOs detonating in the atmosphere release intense heat and create very high blasts of wind that can reach the ground.

"So yes, you do have to sweat the small stuff," Boslough told SPACE.com.

Also, a space rock big enough to make it deeper into the Earth?s atmosphere before it explodes can result in a sizzling jet of gases that incinerates anything volatile on the ground. Vegetation would be vaporized. Rocks would melt to form glass ? in short, a hellish explosion.

A similar situation is thought to have occurred in the Libyan desert some 30 million years ago, Boslough said. The region was strewn with surface material fused into glass. Large deposits of shattered glass were discovered where there should be none.

"Just statistically, it?s almost certain that the next destructive impact will be an airburst," Boslough said.

More and more of the big NEOs are being found, he said, so the statistical probability of Earth getting slam-dunked by a large object is going down.

"But there are many, many more small ones," Boslough said, advocating a priority on spotting less hefty, imminent impactors. "If big dollars are to be spent, I think they should be spent on more telescopes."

If a small NEO were discovered, say, two weeks in advance, "we have no choice but to take the hit," Boslough said.

In terms of planetary defense and mitigation efforts, Boslough advised focusing more attention on small airbursting objects, with "mitigation being a form of civil defense."

Tunguska fallout

The classic asteroid event occurred 102 years ago in Tunguska, Boslough said. It involved an object that broke up in a cascading way, leading to a rapidly expanding fireball and subsequent blast wave.

"That blast wave hit the ground, and the wind associated with it was high enough to actually blow over trees," he said.

The downed trees covered at least 2,000 square kilometers (more than 770 square miles) ? with no crater associated with the explosion located.

Boslough said that, in his opinion, the Tunguska asteroid was probably a 40-meter (131-foot) object. "Tunguska wasn?t the lower threshold. You could imagine something 30 meters (98 feet) across," he said, and in that case, it would explode with a little bit less energy and a little higher in the atmosphere.

"But if you just happened to be directly under it, yes, it could be fatal," Boslough added.

Boslough stressed that the probability of a Tunguska is on the order of once every thousand years. ?But the next object that has the chance of killing somebody is almost certainly going to be an airburst like Tunguska ? maybe bigger, maybe smaller,? he said.

Continuing threat

Other panel members of the AIAA session, while highlighting varying aspects of NEO research, concurred about the troublesome issue of smaller incoming objects.

"We talk about the big ones all the time, and we?re getting rid of the threat for those," said Bill Ailor, director of the Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies.

"But the small ones are going to be a continuing threat. And the challenge is what do we do about that," said Ailor, also a leading planetary defense expert at The Aerospace Corp. in El Segundo, Calif. ?"We might not see them in time."

Similar in view was Don Yeomans, manager of NASA?s Near-Earth Object Program Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

"We?re doing very well with detecting the large ones. But we?ve got a long way to go for the small ones," Yeomans added.

His message regarding planetary defense:

"We need to find them before they find us."

- 5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids

- Images - Asteroids Up Close

- Brilliant Fireball Over New Mexico Caught in Video

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines and has written for SPACE.com since 1999.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.