Small World Beyond Neptune Covered in Ice

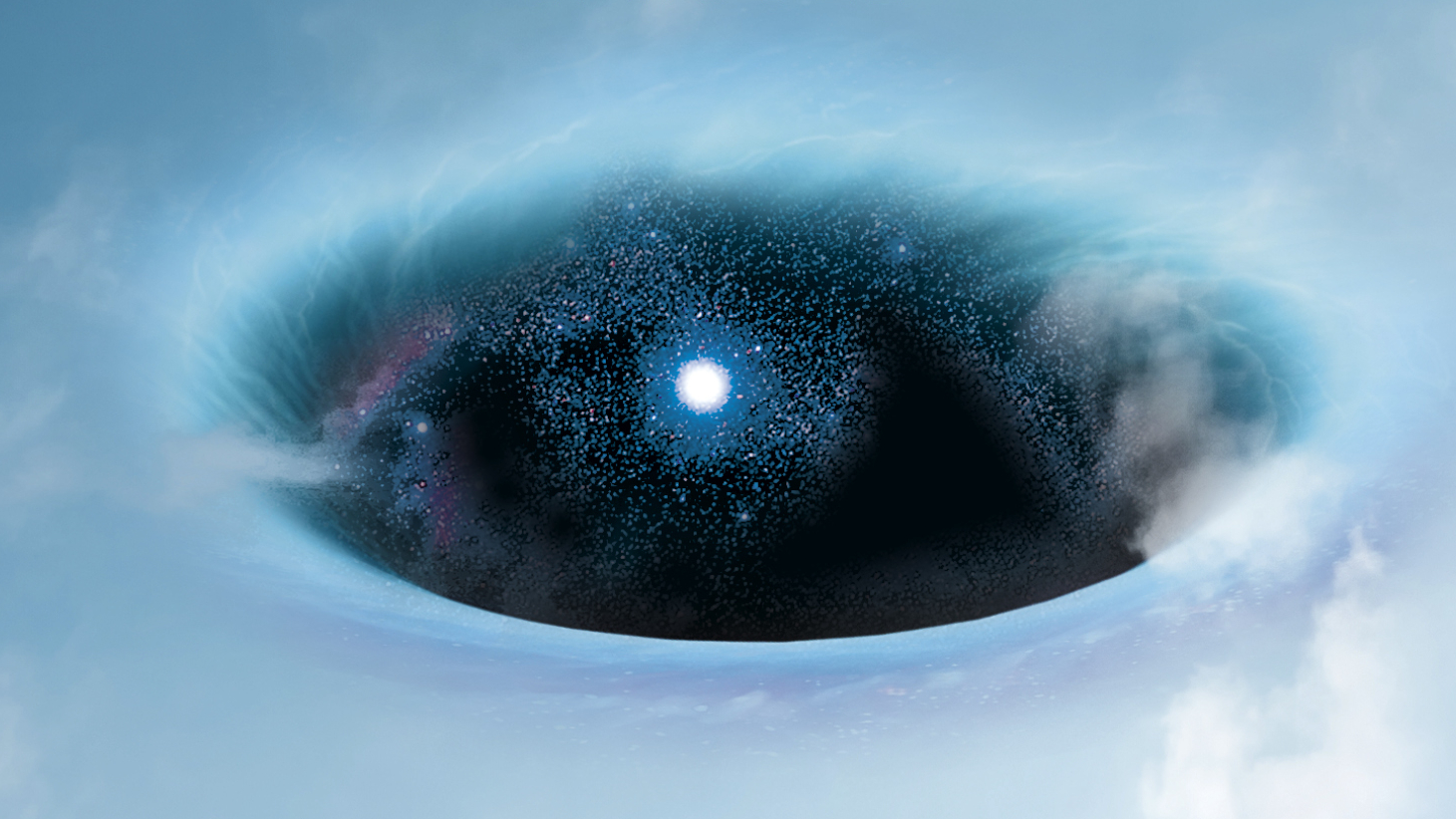

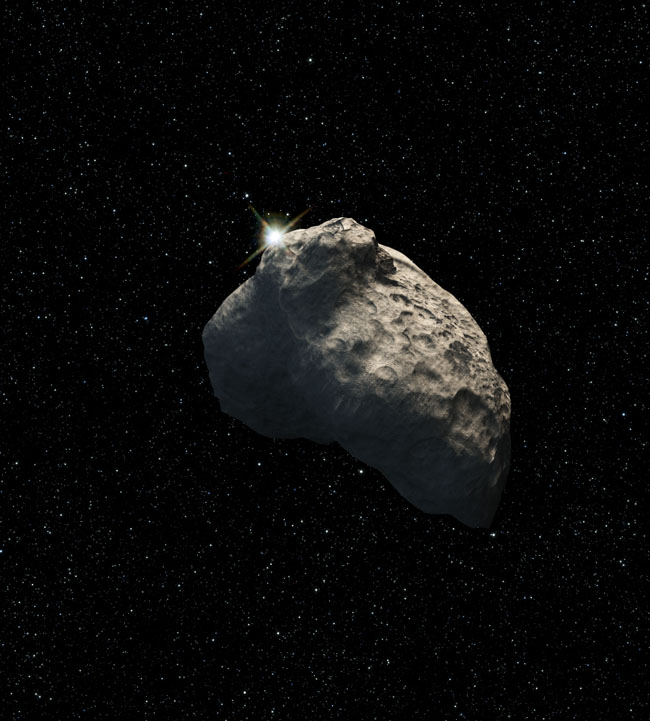

A small space rock that orbits the sun from out beyondNeptune is almost completely coated in water ice, according to a new study thatallowed astronomers ?to estimate the object's size by watching it pass in frontof a star.

The icy, rock body ? dubbed KBO 55636 ? lies in an outerregion of our solar system called the Kuiper Belt, which contains at least 70,000small bodies orbiting farther than Neptune. The region extends out to roughly70 times the distance between the sun and Earth. (The former planetPluto ? now categorized as a dwarf planet ? is also a Kuiper Belt object).

Learning details about these objects is generally difficultbecause they are relatively small, distant and dim.

Bright, small and covered in ice

The researchers decided to try a new method of estimatingone body's size by tracking it as it passed in front of a distant star ? anoccurrence known as a stellar occultation. The astronomers measured the amountof time it took the body to pass in front of the star by watching as the starblinked out and its light was obscured.

This time measurement, combined with already-known velocityof the object, allowed the scientists to estimate that KBO 55636 is about 89miles (143 km) wide.

The astronomers then used the size of the body in concertwith a measure of its brightness to estimate its albedo, which is a measure ofhow strongly it reflects light.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

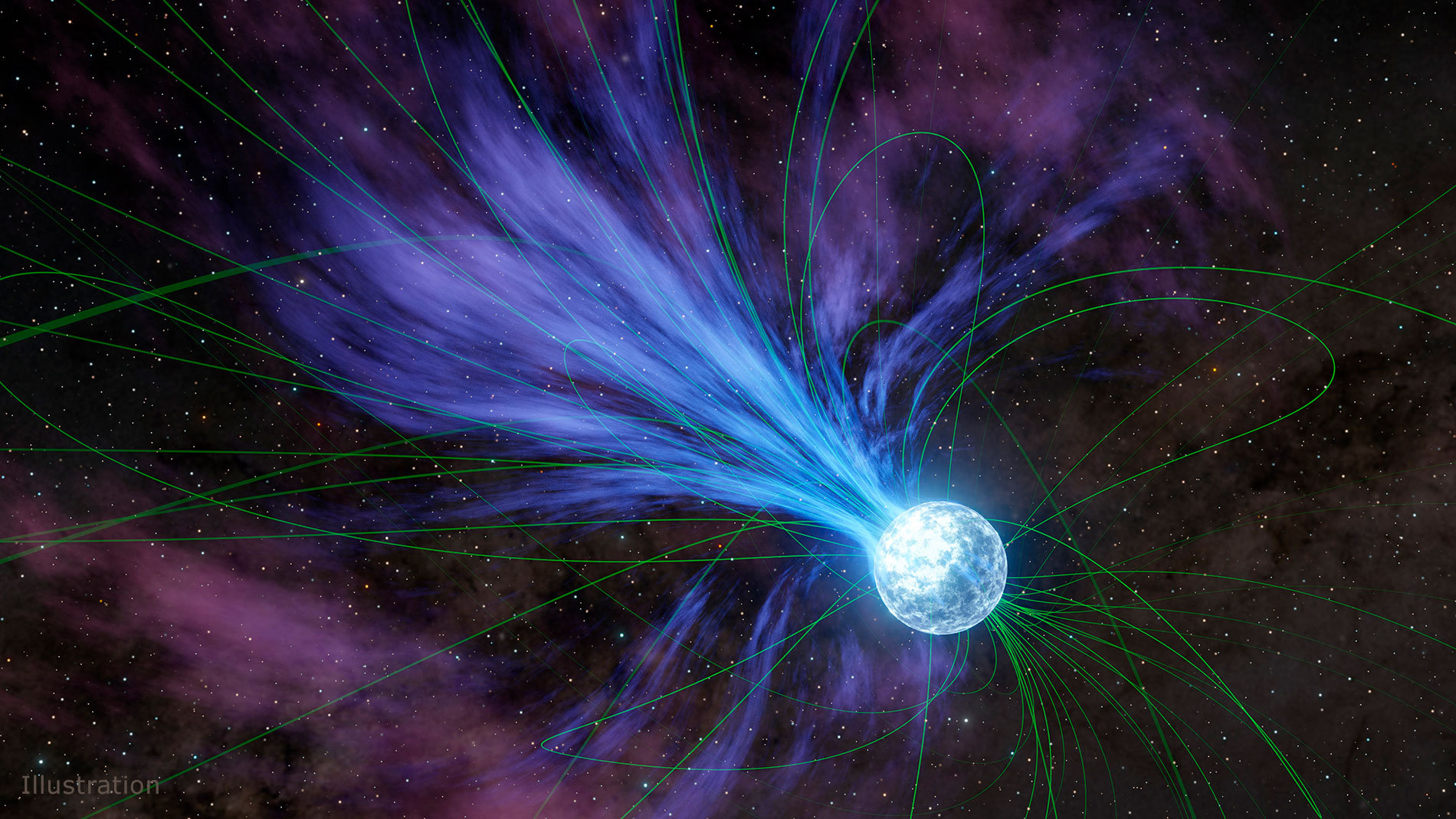

"That turned out to be very high, almost 90 percent,"said lead researcher James Elliot, an astronomer at MIT in Cambridge, Mass."That?s consistent with it having a very highly reflective surface like waterice."

The finding was surprising because such old, distant bodiestend to have weathered, dull surfaces.

"Objects orbiting that far out in space get generallydarkened by accumulating dust," Elliot told SPACE.com. "We don?t havean explanation for how it could stay so pristine."

Shards of something larger

The researchers think KBO 55636 might have broken off alarger KuiperBelt object, the dwarf planet Haumea,when that body was impacted by a smaller space rock and pieces of its icysurface were broken off.

Astronomers have tried using the stellar occultation methodbefore to study Kuiper Belt objects, but no group has succeed until now becauseit's very difficult to catch the transit at precisely the right moment and fromthe right spot.

In order to hedge their bets, Elliot and colleagues had 18different telescopes positioned in various locations around the Earth to makesure that at least one got a perfect view.

"The idea was to counteract the error in orbit predictionwith blanket coverage on the Earth so that the chances of missing it were verylow," Elliot said.

The plan succeeded, and the researchers managed to catch atleast one spot-on view.

Because these Kuiper Belt objects are thought to date fromsome of the earliest epochs of our solar system, the discovery helps scientistsbuild up a better idea of its history over time.

"By studying these and what they're made of, we caninfer what the early conditions were like in the solar system when the planetswere formed," Elliot said.

The astronomers detail their findings in the June 17 issueof the journal Nature.

- New Solar System Guide: The Latest Lingo

- OutThere: Water, Water Everywhere

- Images: Our New Solar System

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.