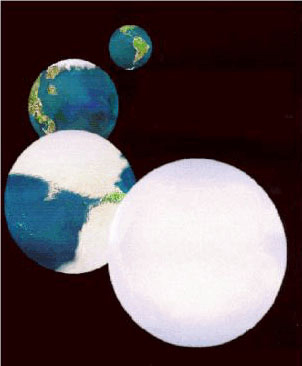

'Snowball Earth' Scenario Plunged Our Planet Into Million-Year Winters

Thesedays the climate news is all about global warming,but global freezing was the biggest climate worry in Earth's distantpast.

Longperiods of severe cold ? like Ice Ages on steroids ?brought glaciers down to the equator and froze much if not all of theoceans.

Scientistsstill debate what triggered these so-called SnowballEarths,but equally uncertain is how the Earth unfroze itself.One research group is studying the hyper-greenhouse warming that wouldbeneeded to end a million-year-long winter.

Theevidence for Snowball Earths comes from paleomagneticdatataken from ancient glacial deposits. From their magnetic properties,geologistscan tell that some of these ice-induced rocks originated from lowlatitudes.This surprising result implies a cold planet that only would get colderas theice reflected away more heat.

"Onceyou have ice cover in the tropics, it all'Snowballs' from there," says Alexander Pavlov of the University ofArizona.

Icereflects more than twice the sunlight of bare groundand more than five times that of water, so as the ice spread, less heatwasretained at the surface. The average global temperature is estimated tohavedropped to minus 50 degrees Celsius (minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit).

"Thisis why it is so hard to escape a Snowball,"Pavlov says. "There is much less radiation being absorbed to warm theplanet."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Butescape the Earth did. Pavlov and his colleagues are modeling thenecessaryconditions that would push the icy Snowball temperatures back to a morecomfortable level.

Aspart of NASA's Astrobiology: Exobiology and Evolutionary Biologyprogram, theyalso will be considering the implications in the search for habitableplanets.If breaking out of a Snowball event turns out to be very difficult,then otherworlds that we would expect to have liquid water instead may bepermanentlyfrozen.

Deepfreeze

Thegeologic record bears the signatures of three Snowball Earths, althoughtheremay have been more. The first event occurred around 2.3 billion yearsago andseems to roughly coincide with the riseof atmosphericoxygen.

Theother two happened more recently at 710 and 640 million years ago.Scientistshave proposed several theories for whatcaused theSnowball Earths.The most well-known of these involves a decrease in heat-trappingcarbondioxide when too many continents drifted near to the equator.

Itmight seem strange that atmospheric levels of CO2might be controlled by continental position, but the connection isthrough thechemical weathering of rocks. Carbon dioxide in the air dissolves intorainwater, creating carbonic acid that dissolves rock minerals likesilicate.Through the reaction, the carbon dioxide s transformed into carbonate,thusreducing the amount of this greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.

Typically,this weathering is faster where the climate iswarm, so having most of the continents along the equator shouldincreaseweathering and lead to a significant drop in CO2 that will chill theplanet.

Thereis some debate among scientists over just how muchof the Earth was covered in ice during Snowball episodes. Manybiologists do not think life on Earth could have survived being lockedunder akilometer-thick sheet of ice, so they argue that there was open watersomewherein the tropical seas.

However,Pavlov believes that it is very hard to preventice from going everywhere once it reaches around 35?latitude. Moreover, thereis geologic evidence that suggests the ocean was effectively cut-offfrom theatmosphere during the extended glacial periods.

Breakingthe ice

Assumingthat the planet did freeze over completely, howdid the temperature trend ever reverse?

Previously,researchers suggested that the Earth couldre-warm itself by turning back the dial on carbon dioxide. Volcanoeswould beconstantly releasing CO2, and there would be virtually no weathering onanice-covered planet to consume this greenhouse gas.

Calculationshave shown that once the atmosphere hasaccumulated 0.2 bars-worth of CO2 (over 600 times what we have now),thegreenhouse warming would be enough to start melting the ice.

However,there are some holes in this warming model.Carbon dioxide will condense into "dry ice" at around minus 80degrees Celsius (minus 112 F). The wintertime polar temperature shoulddropbelow this limit during a Snowball episode, so a large fraction of CO2couldend up being trapped in seasonal ice caps at the poles (similar to whathappenson Mars).

Pavlovand his colleagues are currently redoing themodels to account for CO2 condensation and evaporation. They also willbelooking at whether clouds of CO2 might form that could block some ofthesunlight from reaching the ground.

Itmay turn out that carbon dioxide from volcanoes won'tbe enough to thaw out the planet. His group will therefore consider theeffectof other greenhouse gases, such as methane released from ice deposits,orsulfur dioxide emitted from volcanoes.

Theteam also will be readdressing the reflection, or"albedo" of the ice. Often this is treated as a single parameter, butPaul Hoffman from Harvard University says that the buildup of dust orsalt onthe surface, as well as the daily melt cycles, can have a big effect onjusthow much of the Sun's heat gets reflected away rather than absorbed.

"Tropicalice albedo is the 'elephant in the room'in Snowball modeling," says Hoffman, who is not involved in thisproject.

Snowballselsewhere?

Ourplanet was able to escape its Snowball events, butwould other planets be so lucky?

"Themore landmass a planet has, the better it isprotected from runaway Snowball," Pavlov says. "It is much harder tobuild a glacier inside a large continent if it is not at the pole."

Soa watery planet with little or no dry land might getitself stuck in a Snowball and never escape. Astronomers eventually mayhave toconsider that too much water can be a bad thing when it comes to thehabitability of a planet.

"Iwould say that the main conclusion is that weshould not be focused so much on the water-rich planets," Pavlov says."Dry planets with some water can be habitable at farther distances fromtheir stars."

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.