Europa: A guide to Jupiter's icy moon

Europa is one of the most intriguing moons of the solar system.

Europa is one of the Galilean moons of Jupiter, along with Io, Ganymede and Callisto.

Astronomer Galileo Galilei gets the credit for discovering these Galilean moons, among the largest in the solar system. Europa is the smallest of the four but it is one of the more intriguing satellites.

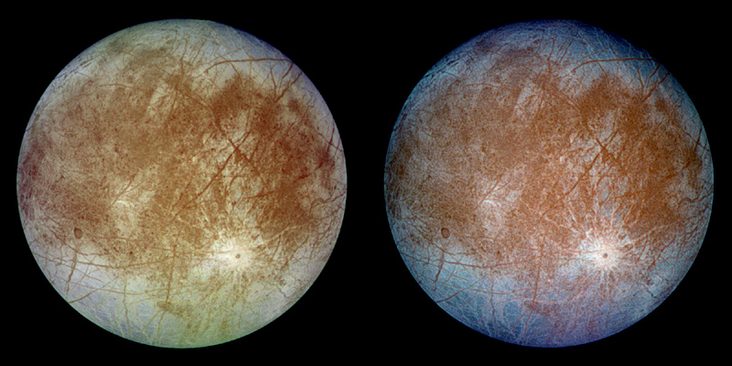

The surface of Europa is frozen, covered with a layer of ice, but scientists think there is an ocean beneath the surface. The icy surface also makes the moon one of the most reflective in the solar system.

Related: The 10 weirdest moons in the solar system

Researchers using the Hubble Space Telescope spotted a possible water plume jetting from Europa's south polar region in 2012. A different research team, after repeated attempts to confirm the observations, saw apparent plumes in 2014 and 2016. The researchers cautioned that the plumes haven't yet been fully confirmed, but they do provide a suggestion that there is water in Europa's ocean jetting to the surface.

Several spacecraft have conducted flybys of Europa (including Pioneers 10 and 11 and Voyagers 1 and 2 in the 1970s). The Galileo spacecraft carried out a long-term mission in the Jovian neighborhood between 1995 and 2003.

Two missions are planned to visit Europa and other Jovian moons within the next decade, ESA's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission and NASA's Europa Clipper.

Europa facts

Age: Europa is estimated to be about 4.5 billion years old, about the same age of Jupiter.

Distance from the sun: On average, Europa's distance from the sun is about 485 million miles (or 780 million kilometers).

Distance from Jupiter: Europa is Jupiter's sixth satellite. Its orbital distance from Jupiter is 414,000 miles (670,900 km). It takes Europa three and a half Earth days to orbit Jupiter. Europa is tidally locked, so the same side faces Jupiter at all times.

Size: Europa is 1,900 miles (3,100 km) in diameter, making it smaller than Earth's moon, but larger than Pluto. It is the smallest of the Galilean moons.

Temperature: Europa's surface temperature at the equator never rises above minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 160 degrees Celsius). At the poles of the moon, the temperature never rises above minus 370 F (minus 220 C).

Missions to Europa

- Pioneer 10 (1973 flyby of Jupiter system). This passed too far away from Europa to get a detailed picture, but the mission did note some variations in albedo (brightness) on the moon's surface.

- Pioneer 11 (1974 flyby of Jupiter system). The spacecraft made a flyby of Europa at nearly 375,000 miles (600,000 km) away, only allowing it to see some variation on the surface.

- Voyager 1 (1979 flyby of Jupiter system). Made a distant flyby of Europa, and also yielded insights about how the gravity of one moon in Jupiter's system influences the gravity of others. For example, Io's volcanism was traced in part to interaction of Io with the moons, as well as with massive Jupiter.

- Voyager 2 (1979 flyby of Jupiter system). One of its major discoveries was confirming brown stripes across the surface of Europa, suggesting cracks in the icy surface.

- Galileo (orbited Jupiter between 1995-2003). Its most famous discovery at Europa was finding strong evidence of an ocean beneath the icy crust at the moon's surface.

- Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) launched on April 14, 2023, and is currently embarking on its 8-year journey to the Jovian neighborhood where it is expected to arrive in 2031. JUICE will look for molecules, such as organic molecules, that are associated with life-giving processes. (Organics are common in the solar system, but the molecules themselves do not always indicate life.)

- Europa Clipper (proposed to launch in 2024). Will fly by Europa dozens of times. One of its major goals is to seek out evidence of the apparent plumes that Hubble researchers spotted several times.

Who discovered Europa?

Galileo Galilei discovered Europa on Jan. 8, 1610.

It is possible that German astronomer Simon Marius (1573-1624) also discovered the moon at the same time. However, he did not publish his observations, so it is Galileo who is most often credited with the discovery. For this reason, Europa and Jupiter's other three largest moons are often called the Galilean moons. Galileo, however, called the moons the Medicean planets in honor of the Medici family.

It is possible Galileo actually observed Europa a day earlier, on Jan. 7, 1610. However, because he was using a low-powered telescope, he couldn't differentiate Europa from Io, another of Jupiter's moons. It wasn't until later that Galileo realized they were two separate bodies.

The discovery not only had astronomical, but also religious implications. At the time, the Catholic Church supported the idea that everything orbited the Earth, an idea supported in ancient times by Aristotle and Ptolemy. Galileo's observations of Jupiter's moons — as well as noticing that Venus went through "phases" similar to our own moon — gave compelling evidence that not everything revolved around the Earth.

As telescopic observations improved, however, a new view of the universe emerged. The moons and the planets were not unchanging and perfect; for example, mountains seen on the moon showed that geological processes happened elsewhere. Also, all planets revolved around the sun. Over time, moons around other planets were discovered — and additional moons found around Jupiter.

Marius, the other "discoverer," first proposed that the four moons be given their current names, from Greek mythology. But it wasn't until the 19th century that the moons were officially given the so-called Galilean names we know them by today. All of Jupiter's moons are named for the god's lovers (or victims, depending on your point of view). In Greek mythology, Europa was abducted by Zeus (the counterpart of the Roman god Jupiter), who had taken the form of a spotless white bull to seduce her. She decorated the "bull" with flowers and rode on its back to Crete. Once in Crete, Zeus transformed back to his original form and seduced her. Europa was the queen of Crete and bore Zeus many children.

Europa FAQs answered by an expert

We asked Lorenz Roth, a planetary astronomer at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, who specializes in the study of solar system moons including the large moons of Jupiter, also known as the Galilean moons, some questions about Europa.

Lorenz Roth is a planetary astronomer at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, who specializes in the study of solar system moons.

How big is Europa?

Europa is very similar to our Earth's moon in size. Its diameter is 1/4 of the Earth's diameter.

What is Europa made of?

Europa is mostly made of silicate rock (chemical formula SiO_x). The outermost layer is yet made of water ice — H2O.

Does Europa have water?

Indeed, there are huge amounts of H2O and there is evidence that below the ice crust H2O exists in liquid form in a global subsurface ocean.

Could Europa support life?

Europa is one of the most promising candidates. There is the water ocean under the ice crust which likely has a real ocean floor, so it is in contact with the silicate rock at the bottom.

Europa characteristics

A prominent feature of Europa is its high degree of reflectivity. Europa's icy crust gives it an albedo — light reflectivity — of 0.64, one of the highest of all of the moons in the entire solar system.

Scientists estimate that Europa's surface is about 20 million to 180 million years old, which makes it fairly young.

Pictures and data from the Galileo spacecraft suggest Europa is made of silicate rock, and has an iron core and rocky mantle, much like Earth does. Unlike the interior of Earth, however, the rocky interior of Europa is surrounded by a layer of water and/or ice that is between 50 and 105 miles (80 and 170 km) thick, according to NASA.

From fluctuations in Europa's magnetic field that suggests a conductor of some sort, scientists also think there is an ocean deep beneath the surface of the moon. This ocean could contain some form of life. This possibility of extraterrestrial life is one of the reasons interest in Europa remains high. In fact, recent studies have given new life to the theory that Europa can support life.

The surface of Europa is covered with cracks. Many believe these cracks are the result of tidal forces on the ocean beneath the surface. It's possible that, when Europa's orbit takes it close to Jupiter, the tide of the sea beneath the ice rises higher than normal. If this is so, the constant raising and lowering of the sea caused many of the cracks observed on the surface of the moon.

Obtaining samples of the ocean may not require drilling through the icy crust, should the repeated observations of possible plumes turn out to be actual jets of water. While researchers spotted evidence in 2012, 2014 and 2016, the true nature of the plumes — and why they appear sporadically — requires more observations.

In 2014, scientists found that Europa may host a form of plate tectonics. Previously, Earth was the only known body in the solar system with a dynamic crust, which is considered helpful in the evolution of life on the planet.

Could there be life on Europa?

The presence of water beneath the moon's frozen crust makes scientists rank it as one of the best spots in the solar system with the potential for life to evolve.

The icy depths of the moons are thought to contain vents to the mantle much as oceans on Earth do. These vents could provide the necessary thermal environment to help life evolve.

If life exists on the moon, it may have gotten a kick from deposits from comets. Early in the life of the solar system, the icy bodies may have delivered organic material to the moon.

In 2016, a study suggested that Europa produces 10 times more oxygen than hydrogen, which is similar to Earth. This could make its probable ocean friendlier for life — and the moon may not need to rely on tidal heating to generate enough energy. Instead, chemical reactions would be enough to drive the cycle.

Upcoming missions to Europa

Two upcoming missions to Europa are the European Space Agency's (ESA) JUICE mission which launched in April 2023, and NASA's Europa Clipper mission due to launch in 2024.

Despite launching after JUICE, the Europa Clipper mission will Europa Clipper will reach Jupiter before JUICE, on April 11, 2030. The spacecraft will contain nine scientific instruments on board including cameras, radar to peer beneath the ice and try to figure out its thickness, a magnetometer to measure the magnetic field (and by extension, how salty the ocean is), and a thermal instrument to search for signs of eruptions. The flybys would range in height between 16 miles (25 km) and 1,700 miles (2,700 km). This brings the flybys well into the radiation-heavy zone of Europa, which is tough for a spacecraft to survive. Bringing the spacecraft in and out of the zone will extend its lifetime and make it easier to transmit data back to Earth.

One of Europa Clipper's priorities will be to follow up on the Hubble observations of plumes. "If the plumes' existence is confirmed, and they're linked to a subsurface ocean, studying their composition would help scientists investigate the chemical makeup of Europa's potentially habitable environment while minimizing the need to drill through layers of ice," NASA said in a statement.

ESA's JUICE mission will visit Jupiter and three of its icy moons: Europa, Callisto and Ganymede. A single orbital spacecraft with no lander, JUICE will orbit Ganymede, the solar system's largest moon, becoming the first probe to orbit a planetary moon other than Earth's. Once it gets to Europa, the mission will look at organic molecules and other components that could make the moon friendly to life. Also, the spacecraft will probe how thick the crust is, particularly over any active regions it finds.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor