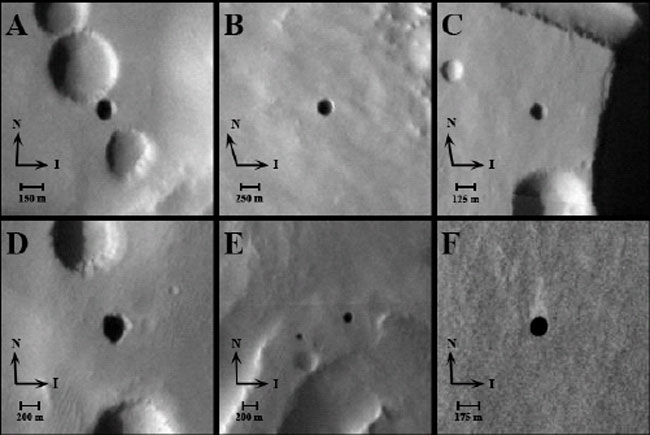

A Mars-orbiting satellite recently spotted seven dark spots near the planet's equator that scientists think could be entrances to underground caves.

The football-field sized holes were observed by Mars Odyssey's Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) and have been dubbed the seven sisters --Dena, Chloe, Wendy, Annie, Abbey, Nikki and Jeanne--after loved ones of the researchers who found them. The potential caves were spotted near a massive Martian volcano, Arisa Mons. Their openings range from about 330 to 820 feet (100 to 250 meters) wide, and one of them, Dena, is thought to extend nearly 430 feet (130 meters) beneath the planet's surface.

The researchers hope the discovery will lead to more focused spelunking on Mars.

"Caves on Mars could become habitats for future explorers or could be the only structures that preserve evidence of past or present microbial life ," said Glenn Cushing of Northern Arizona University, who first spotted the black areas in the photographs.

A project here on Earth aims to refine the visual and infrared techniques THEMIS used to find the Martian caves and to also develop robots that can one day enter the caverns and explore them.

Practicing on Earth

Called the Earth-Mars Cave Detection Program, the project is preparing to enter phase 2, during which scientists will test their approach in "Mars analogue" sites, terrestrial environments with similarities to Martian landscapes. These sites will include dry, blistering deserts, such as the Mojave in California and the Atacama in Chile, as well as frigid environments like Iceland and Antarctica.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During the first phase of the project, the researchers acquired the thermal signatures of a dozen caves in Arizona and New Mexico using an experimental infrared detector flown aboard an airplane, called the Quantum Well Infrared Photodetector (QWIP), as well as data collected on the ground using a handheld thermal camera.

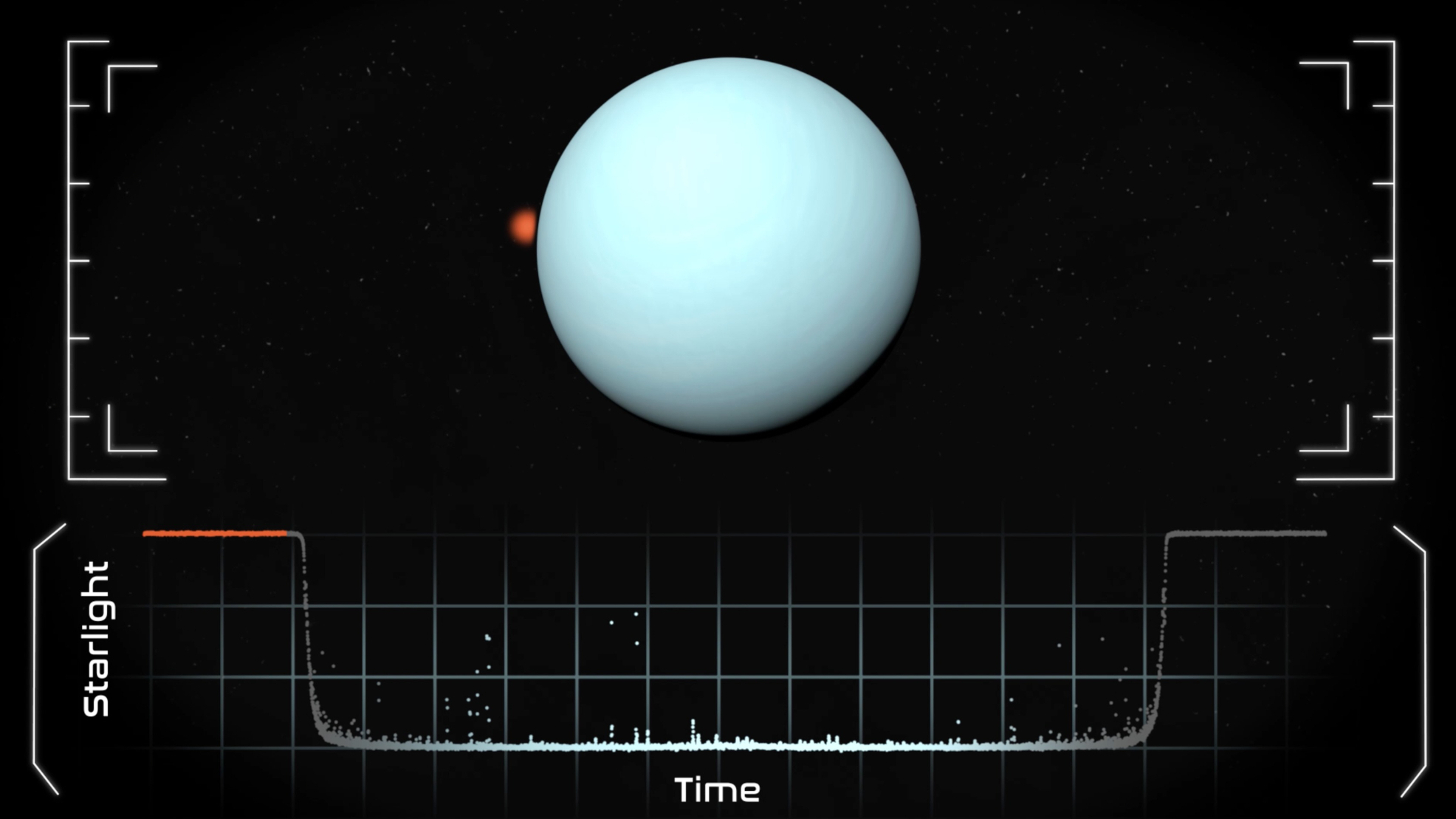

Cave detection using QWIP works by spotting regions in the landscape where temperatures are different from the surroundings. Inside a cave, temperatures are nearly constant due to lack of sunlight. Outside, temperatures fluctuate with the rising and setting of the Sun. At a cave entrance, these two temperature regimes mix together to create a unique thermal signature that, depending on the time of day, can be either warmer or cooler than the surrounding environment.

"The caves show up as hotspots in a sea of cold, or as cold spots in a sea of warmth," said study team member Murzy Jhabvala, chief engineer of the Instrument Systems and Technology Center at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

The data, still being analyzed, look promising. In one series of images, the researchers snapped thermal images of Xenolith Cave in New Mexico over a 24-hour period. The cave opening can be seen clearly in some of the images.

"It jumps out at you," said Jut Wynne, a biospeleologist (cave biologist) with the U.S. Geological Survey and Northern Arizona University. "It lights up like a Christmas tree in the predawn and in the late-night shots. It's a bit more ephemeral during the day shots."

In Phase 2, the researchers will tweak their technique to figure out the best wavelengths to use and optimal times during the day for cave hunting. "In so doing, we're going to take these applications and then apply them to an orbiter platform for Mars," said Wynne, who is also the Earth-Mars Cave Detection Program project leader.

Robotic cave explorers

The project team also aims to design robots that can explore caves on Mars after they have been spotted. Natalie Cabrol, a planetary geologist with NASA Ames and the SETI Institute, will be integral to this part of the project.

Cabrol is a Mars robot veteran. Before Spirit and Opportunity were sent to Mars, she helped engineers perfect their designs by field-testing the robotic rovers in the Atacama Desert in Chile.

The researchers may have to design more than one type of robotic cave explorer. "There are many types of caves," Cabrol said in a telephone interview. "It may be that we come up with one very versatile design ... or we might end up with several designs."

If the caves have a relatively simple structure--like lava tubes, which are caves carved by flowing magma and are relatively simple and straight--a rover-type robot might work, Cabrol said. "I would doubt that a rover, equipped as they are now, would do a good job in a cave" with a more complicated geometry, she said.

Open to ideas

The researchers are also considering other robotic design possibilities, including the deployment of several miniature robots together into a cave.

"You could throw out an array of microbots in a birdshot approach over an area where you think there is a cave," Wynne told SPACE.com . The microbots could then use sonar or some other method to confirm the presence of a cave and pinpoint its location.

Whatever form the team's robotic explorer ultimately takes, it will have to be agile, have some basic sense of self-awareness, sport excellent night vision and have the ability to communicate with one other in some innovative way, since conventional radio communication might not work well in caves, Cabrol said.

"We are very much on the starting line on this," she added. "This is very exciting. This is really the time when ideas are flitting all over the place."

- Future 'Martians' Could Live in Caves

- Microbot Madness: Hopping Toward Planetary Exploration

- Spelunking on Mars: Caves are Hot Spots in Search for Life

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.