Best Time to See Moon Mountains in May Is Now

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It's time to spot some mountains on the moon.

When you look at the moon through binoculars or a small telescope, the first thing you notice is that the lunar surface is divided into two distinct forms of terrain: large dark flat plains and bright mountainous highlands. Both of these are pockmarked by an enormous number of craters of all sizes.

Early observers of the moon assumed that the large flat plains were seas, not knowing that liquid water was not available on the dry, airless surface of the moon, and so named them "maria," the Latin for "seas," singular "mare." [See 45 Apollo Moon Missions in Photos]

"Mare" is pronounced "mah-ray," not like a female horse. They named the lunar highlands for the mountains of Earth, not knowing that the mountains of the moon were formed by a totally different process.

On Earth, mountains are formed by two different processes. Most mountains, and mountain ranges, are formed by tectonic action: the plates that make up the surface of the Earth bump into each other, causing mountains to rise up. Other mountains on Earth are caused by volcanic action: hot magma welling up from the depths of the Earth to deposit itself on the surface as volcanoes.

The moon has neither tectonic plates nor volcanic action. Virtually all of its mountains are the result of impacts by asteroids in the distant past. Early in the moon’s history, there were many gigantic asteroids in the solar system.

When these impacted the moon and planets, they formed craters far larger than the ones we see today, forming the lunar maria and leaving their rims to form lunar mountain ranges. The enormous heat generated by these impacts melted the surface material of the moon and caused it to flow, swamping some craters and mountains, which stand out now as ruins on the surface of the maria.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

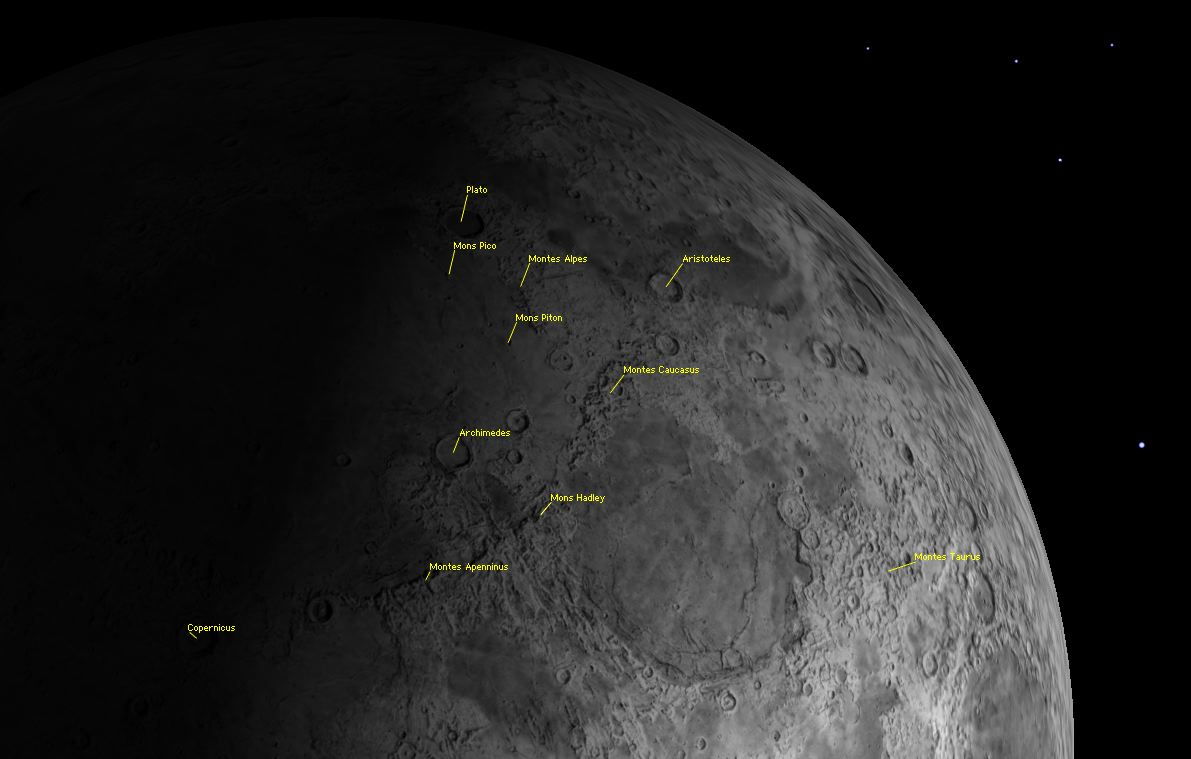

The chart shows some of the mountain features visible this week at the current phase of the moon, around first quarter. Several prominent craters are marked to help you get your bearings: Aristoteles, Plato, Archimedes and Copernicus.

The mountain ranges and individual mountains are labeled with their Latin names, "montes" for mountain ranges and "mons" for individual mountains. Far over to the east are the Taurus Mountains (Montes Taurus), the landing place of the last of the manned lunar explorers, Apollo 17.

Two major mountain ranges divide two other features of the lunar landscape.The Mare Serenitatis ("Sea of Serenity") is separated from the Mare Imbrium ("Sea of Showers") by the Montes Caucasus to the north and the Montes Apenninus to the south. Where these two meet is the prominent mountain Mons Hadley, named for British optician and instrument maker John Hadley (1682–1743). Apollo 15 landed here in July 1971. The lunar Alps, the Montes Alpes, sweep off to the northwest, enclosing the perfect oval crater, Plato.

On the barren floor of the Mare Imbrium are two of the most impressive single mountain peaks on the surface of the moon, Mons Piton and Mons Pico.

The Mons Piton has a base 16 miles (25 kilometers) in diameter and towers 7,380 feet (2,250 m) over the surrounding plain. The Mons Pico is even more impressive, with a base measuring 9 by 16 miles (15 by 25 km) and a height of 7,870 feet (2,400 m). Both of these are named after mountains on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

Although these mountains look impressive under the low light of a rising sun, they really are quite gentle when compared to the mountains of Earth. If you look again in a day or two, they will be practically invisible except for their whiter color.

Enjoy your lunar mountain-climbing expedition.

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, the leader in space science curriculum solutions. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.