For the first time ever, astronomers have directly observed planets in the process of being born.

Scientists have photographed a gas-giant exoplanet forming around a young star called LkCa 15, which lies about 450 light-years from Earth.

"It's exciting, because it's the first time that we've been able to image forming planets directly," study lead author Stephanie Sallum, a graduate student at the University of Arizona, told Space.com. "It gives us a system to follow up in the future, in depth, to really understand the details of how planets form." [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

The LkCa 15 system features a large disk of dust and gas surrounding a sunlike star that's just 2 million years old. Such circumstellar disks commonly surround newborn stars, providing the raw materials from which planets form.

Indeed, previous studies have spotted large gaps in some disks that newly accreting alien worlds likely cleared out. Scientists have even detected disk asymmetries and heat signatures that have been interpreted as evidence of planets inside these gaps.

Such a gap exists in LkCa 15's disk, and one giant protoplanet candidate, known as LkCa 15b, was detected in the system in 2012, at a distance of about 16 astronomical units (AU) from the star. (One AU is the distance from Earth to the sun, about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers.)

To learn more, Sallum and her colleagues zeroed in on the LkCA 15 system using the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT), an observatory in southeastern Arizona that boasts two 27-foot-wide (8.4 meters) primary mirrors.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

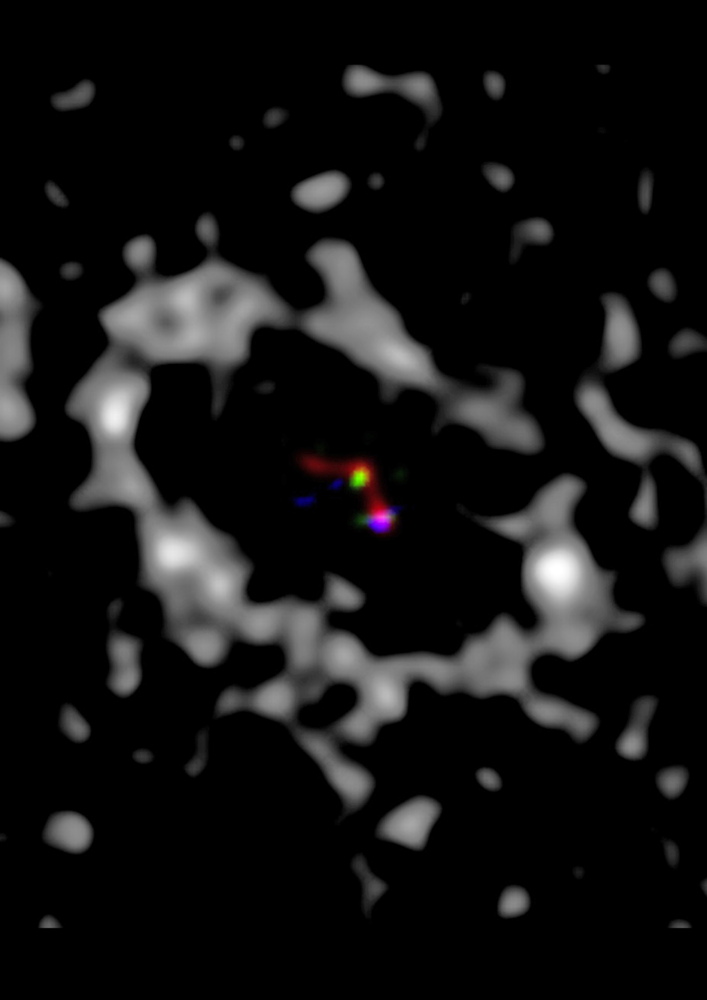

The team confirmed the existence of LkCA 15b, imaging it directly in hydrogen-alpha photons, a type of light that's emitted when superheated material accretes onto a newly forming world. (Like newborn stars, newborn planets are surrounded by disks of feeder material.)

Other LBT observations revealed the presence of another newborn planet, LkCA 15c, inside the gap and suggested that a third (LkCA 15d) exists there as well, study team members report online today (Nov. 18) in the journal Nature.

"We're seeing sources in the clearing," Sallum said. "This is the first time that we've been able to connect a forming planet to a gap in a protoplanetary disk."

"The researchers' discovery provides stringent constraints on planet-formation theories," Zhaohuan Zhu of Princeton University, who was not affiliated with the new study, wrote in an accompanying "News & Views" piece in the same issue of Nature. "For example, such theories now have to explain how a giant planet can form 15-16 AU from its star within 2 million years, and still be growing after this time."

The new technique demonstrated by Sallum and her team could lead to the discovery of many other newly forming exoplanets, allowing astronomers to learn much more about the distribution of young worlds, Zhu added.

"Such an understanding of the young planet population will shed light on the decades-old problem of planet formation, and reveal how young planetary systems can evolve into older ones such as our solar system, billions of years after they were born," Zhu wrote.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.