How Planets Form: 'It's a Mess Out There'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

New observations of dust around young stars suggests collisions of large asteroid-like objects and fledgling planets are frequent. But that doesn't likely stop the formation of rocky planets like Earth, a process that may well be common, the results suggest.

Based on the violent past of our own solar system, many astronomers had assumed planet formation was a chaotic process involving a lot of smash-ups. The new observations of 266 stars confirm that view and provide new details about just how wild things are.

"It's a mess out there," said George Rieke of the University of Arizona. "We are seeing that planets have a long, rocky road to go down before they become full grown."

Like night-vision goggles, NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope sees infrared light. In this case, it spotted rings of dust around the stars by recording the heat emitted by dust grains lit by the star. In many cases, there is so much dust that it had to have been recently replenished by collisions between large objects, explained Rieke, who led the investigation.

Rocky planets like Earth are thought to form when dust motes around a nascent star gather to form rocks. Rocks collide, and some stick and grow.

"The dust bunnies under your bed grow in a similar way," said Scott Kenyon, a planet-formation theorist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "And after a million years, a dust bunny can get pretty big."

The process is not always smooth. Our Moon is thought to have formed when a Mars-sized object hit Earth shortly after our planet gathered itself together. For a few hundred million years thereafter, impacts of huge asteroids rocked all the worlds of the inner solar system. Craters on the Moon serve as a record of that chaotic time.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

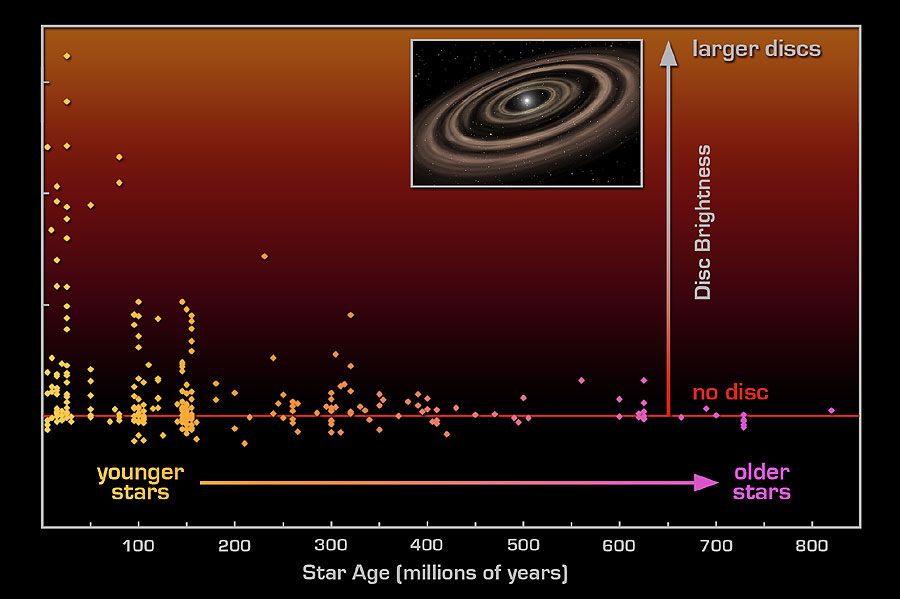

The stars in the new study ranged in age from newborn to about 800 million years old, covering a time frame corresponding to the Moon's formation here and on into the emergence of life on Earth. Earth is now about 4.5 billion years old, with the Sun about 100 million years older.

According to Rieke, some theorists had not expected collisions to be so frequent as the Spitzer observations suggest. The study also showed intriguing variations among some stars.

"We thought young stars, about one million years old, would have larger, brighter discs, and older stars from 10 to 100 million years old would have fainter ones," Rieke said. "But we found some young stars missing discs and some old stars with massive discs."

In general, however, the data from most dust disks in the study reveal a gradual reduction in brightness related to a steady decline in significant collisions.

Kenyon, who was not involved in the study, said it provides a movie of sorts about planet formation. Astronomers previously had perhaps a half-dozen snapshots of dust disks around young stars -- "an astronomical freak show," as Rieke put it.

"Now with several hundred frames we can see the plot," Kenyon said in a teleconference with reporters, set up Monday by NASA.

Importantly, the new set of observations detail dust disks that are relatively close to the stars, the region analogous to where Venus, Earth and Mars reside. In previous work, researchers have mostly witnessed dust farther from stars, equivalent to the region of our solar system near and beyond the outermost planets.

The stars in the new study are all within 500 light-years of Earth. Most are about 2.5 times the mass of the Sun, similar enough that the processes around them ought to be similar to what occurred around the young Sun, Rieke said.

Archive data from the Infrared Astronomical Satellite and the Infrared Space Observatory contributed to the study. The results will be detailed in the Astrophysical Journal.

- The Moon's Formation

- Building Gas Giant Planets

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.