Scientists have learned some key characteristics of a gigantic asteroid and its two moons, with a bit of help from sharp-eyed amateur astronomers.

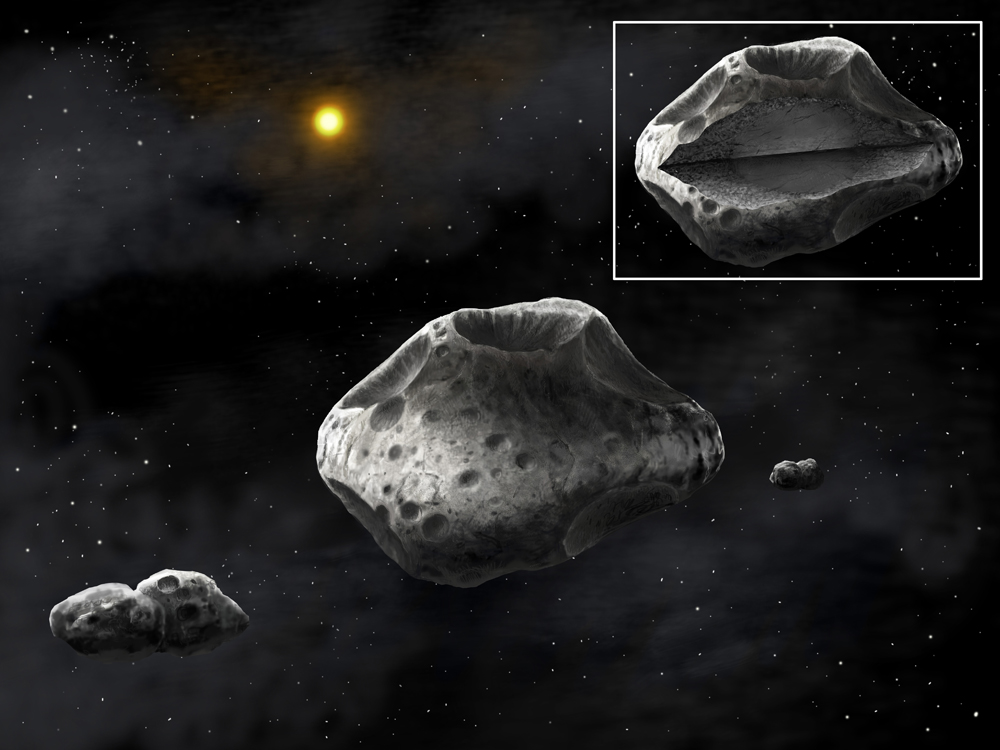

Observations by amateurs helped researchers determine that asteroid (87) Sylvia, a space rock 168 miles wide (270 kilometers), appears to have an irregular shape and a dense, spherical core surrounded by a layer of relatively fluffy material. Further, the asteroid's larger moon, Romulus, is about 15 miles (24 km) wide, scientists said.

"Combined observations from small and large telescopes provide a unique opportunity to understand the nature of this complex and enigmatic triple asteroid system," study lead author Franck Marchis, of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif., said in a statement. [Photos: Asteroids in Deep Space]

"Thanks to the presence of these moons, we can constrain the density and interior of an asteroid, without the need for a spacecraft’s visit," he added. "Knowledge of the internal structure of asteroids is key to understanding how the planets of our solar system formed."

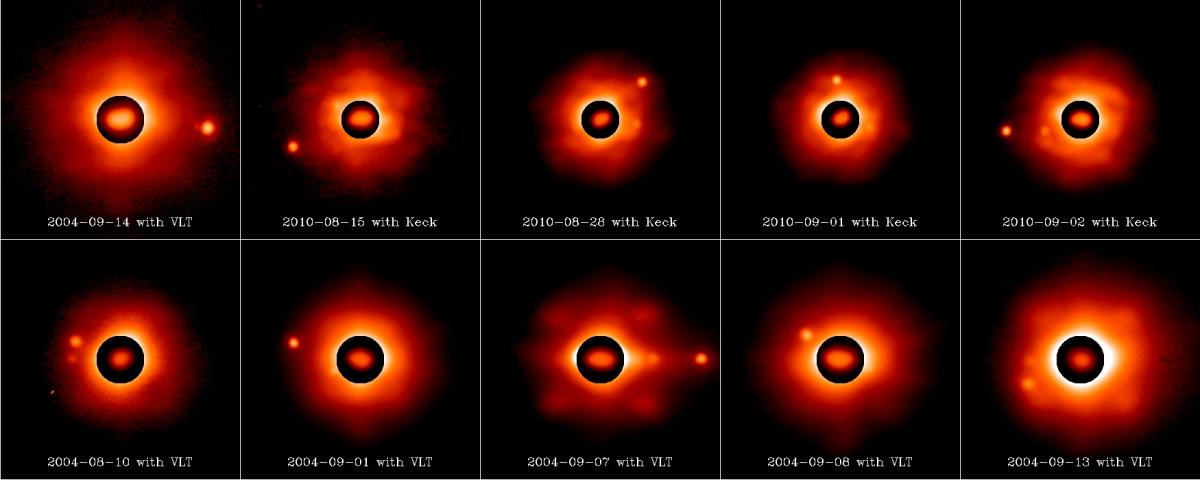

Marchis and his team conducted a long-term observing campaign of (87) Sylvia, which lies in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. They used big telescopes equipped with sophisticated adaptive-optics systems, such as the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and European Southern Observatory instruments in Chile.

These observations helped the scientists devise accurate models of the triple-asteroid system, allowing them to predict the position of the two moons around the big "primary" space rock at any time.

These models were put to the test on Jan. 6, 2013, when (87) Sylvia passed in front of a distant bright star, an event known as an occultation.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research team collaborated with EURASTER, a group of amateur and professional astronomers, to observe this occultation, which was visible across a narrow stretch of Europe from France to Greece. About 50 people turned their telescopes to the skies, and a dozen managed to spot the occultation, which lasted between four and 10 seconds depending on the observing location.

"Additionally, four observers detected a two-second eclipse of the star caused by Romulus, the outermost satellite, at a relative position close to our prediction," study team member Jérôme Berthier, an astronomer at the Paris Observatory, said in a statement. "This result confirmed the accuracy of our model and provided a rare opportunity to directly measure the size and shape of the satellite."

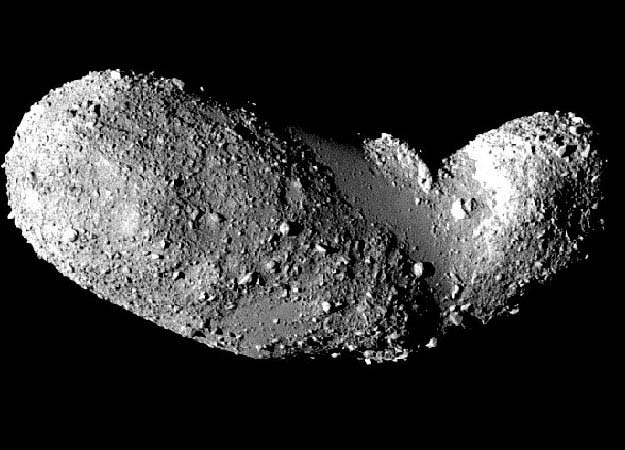

That shape resembles a dumbbell, suggesting that Romulus may have formed from the debris shed by a proto-Sylvia after a massive impact billions of years ago, researchers said.

Marchis presented the results today (Oct. 7) at the 45th annual Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Denver.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.