Forty years ago this week, one of the brightest and most spectacular comets ever seen was putting on a memorable show in the morning twilight sky. It came out of nowhere and was described by some as being 10 times brighter than the full Moon.

On the morning of September 19, 1965 (Tokyo Time), two Japanese amateur astronomers, Kaoru Ikeya and Tsutomu Seki, independently discovered a nearly naked-eye comet that somehow managed to escape detection until it was less than 100 million miles from the Sun. The first dispatch stated that:

"Dr. H. Hirose, Tokyo Astronomical Observatory, announces the discovery of a comet by Ikeya and Seki."

Both of these young men had made other comet discoveries, but this one would soon catapult them to fame. In the days that followed their initial sighting, additional observations were reported and preliminary orbits were computed, but these gave no hint that this new comet was anything out of the ordinary.

The surprise came on October 1 when it was announced that Comet Ikeya-Seki was going to literally graze the Sun. According to calculations by Dr. Leland E. Cunningham of the Leuschner Observatory (Berkeley, California), Comet Ikeya-Seki would swing around the Sun on October 21, passing a mere 291,000 miles from the solar surface, probably becoming at least as bright as magnitude -7 (about eight times brighter than Venus)! Dr. Cunningham also cited Ikeya-Seki's "very close resemblance to that of the Great Sun-Grazing Comet of 1882 and its family."

The sungrazing family of comets

In the year 1888 astronomer Heinrich Kreutz (1854-1907) noted that sungrazing comets, all followed along approximately the same orbit.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Apparently, they were all fragments of a single giant comet, which had fragmented in the distant past. And it's quite probable that these fragments, have themselves broken up repeatedly as they've orbited the sun, resulting in periods ranging from about 500 to 800 years. In honor of his work, this special group of comets is named the Kreutz Sungrazers. Two of these sungrazers, (in 1843 and 1882) not only developed very long tails but also achieved the rare distinction of having been bright enough to be seen in broad daylight with the unaided eye.

With this as a background, Ikeya-Seki suddenly broke onto the scene, and with it, public interest in viewing it increased almost exponentially overnight.

As a youngster, growing up in the Bronx, I can still recall the increasing excitement of watching local and national television news reports on the approaching comet, as well as reading full-page feature articles about it in the local newspapers. Prospective comet viewers were told to look for the brightening comet, low in the east-southeast sky about an hour before sunrise.

Desparately seeking Ikeya-Seki

Unfortunately, in the week leading up to its solar rendezvous, the weather across much of the United States was persistently cloudy, hazy or foggy. East of the Mississippi, literally hundreds of thousands if not millions of people maintained a cold and fruitless vigil each morning at dawn and saw nothing.

I know. I was one of them.

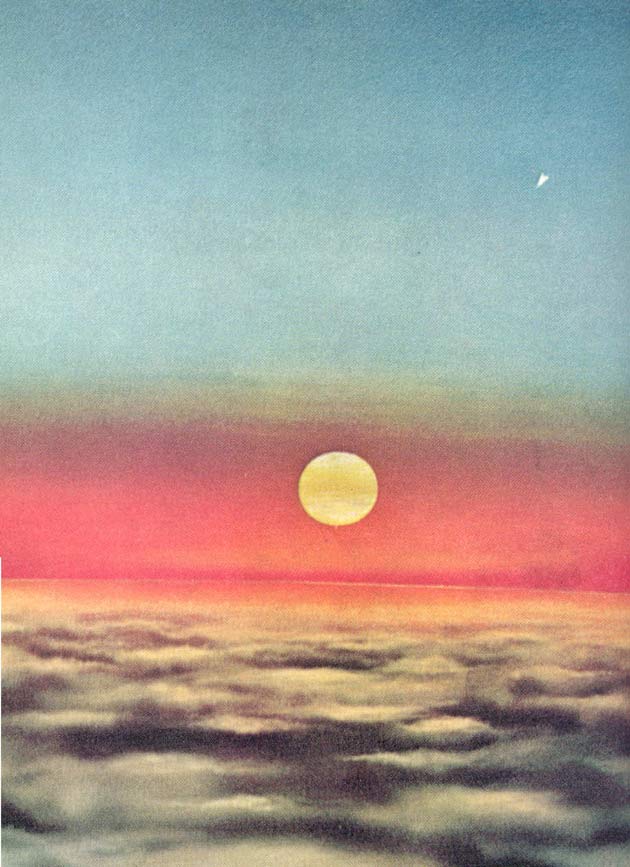

One of the very few easterners lucky enough to catch a naked-eye glimpse of Ikeya-Seki in the broad daylight was astronomer Kenneth Franklin, of New York's Hayden Planetarium who went aloft in a small plane 12,000 feet over West Point, New York. There, just above low-lying clouds and haze, Dr. Franklin was able to view the pale, white, slightly elongated head of the comet above and to the right of the rising Sun. Later that morning, Hayden's in-house artist, Helmut K. Wimmer rendered a painting of this scene based on Franklin's description, which is reproduced here courtesy of Natural History magazine.

Conversely, the weather was clearer over the far western United States so that on October 21, many were treated to an amazing spectacle of a comet so brilliant that it could be easily seen if the Sun was hidden behind the side of a house or just an outstretched hand. "The most splendid thing I have ever seen," noted astronomer Stephen Maran, who observed Ikeya-Seki with 16 x 50 binoculars from Kitt Peak National Observatory, in Arizona.

Many others remarked on the striking curvature of the comet's stubby 2º tail as it whirled in a hairpin curve around the Sun at over a million miles per hour. In Japan the comet was described as appearing "10 times brighter than the full Moon." In addition, a "disruption" of the comet was observed, its nucleus apparently fracturing into two or three pieces.

Curtain falls . . . But the show wasn't over!

After October 21, public interest in Ikeya-Seki dropped off dramatically. This was most unfortunate, because once it pulled far enough away from the Sun and could again be seen against a deep twilit morning sky, the poor weather that plagued many, suddenly changed for the better.

During the final week of October 1965, the morning skies were exceptionally clear for most localities allowing Ikeya-Seki to be readily seen. An incredibly brilliant, twisted tail stretched up from the east-southeast horizon an hour or two before the Sun, appearing like a slender searchlight beam, about as long as the length of the Big Dipper. So bright was this tail, that on Halloween morning, veteran New York comet observer, John Bortle was able to see it despite being enveloped in a heavy local ground fog.

At its maximum length, Ikeya-Seki's tail extended for 70 million miles, ranking it as the fourth largest ever recorded. Only the Great Comets of 1680, 1811 and 1843 had tails stretching farther out into space. While the comet's head faded rapidly, the tail continued to be visible well into November even as the comet moved rapidly away from the Sun.

When will we see the next one?

Comet Ikeya-Seki is moving in an extremely long, narrow elliptical orbit, whose period roughly corresponds to 600-years. But that doesn't mean that our descendants around the year 2565 will be treated to a repeat performance, since the comet essentially departed the scene with its nucleus in shambles.

But that also doesn't necessarily mean that we will never see another bright comet moving in the same orbit. Recall that Ikeya-Seki was identified as a member of the Kruetz Sungrazing group of comets. Until 1978, only about a dozen sungrazing comets had been positively identified.

Beginning in 1979, orbiting space observatories began to detect sungrazing comets using instruments called coronagraphs. A coronagraph is designed to look at the solar atmosphere by blocking out the bright disk of the sun. Tiny sungrazing comets, which normally would be too faint and too near to the glare of the Sun, can be picked up using a coronagraph.

In fact, sungrazers are now routinely being discovered using the Large Angle Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) satellite. Hundreds of SOHO comet discoveries have been made by amateurs using SOHO images on the Internet, and SOHO comet hunters come from all over the world. Toni Scarmato, a high school teacher from Italy, recently discovered SOHO's 999th and 1000th comet August 5 when two tiny comets appeared in the same SOHO image. Nearly 800 SOHO comets have been identified as Kreutz sungrazers. Some are probably just a few meters across; none have survived their sweep around the Sun.

But just when will another large and spectacular member of the Kreutz group, like Ikeya-Seki, appear? No one can say for sure. The last Kreutz Sungrazer to become bright was Comet White-Ortiz-Bolelli in 1970. It's not possible to estimate the chances of another very bright Kreutz comet arriving in the near future. But given that at least 10 have reached naked eye visibility over the last 200 years, another great comet from the Kreutz family almost seems destined to arrive at some point in the future.

Indeed, these comets are like trains of all sizes moving along the same railroad track while passing our station (Earth) in space.

And like an impatient commuter we can only watch and wonder what awaits us up the track!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.