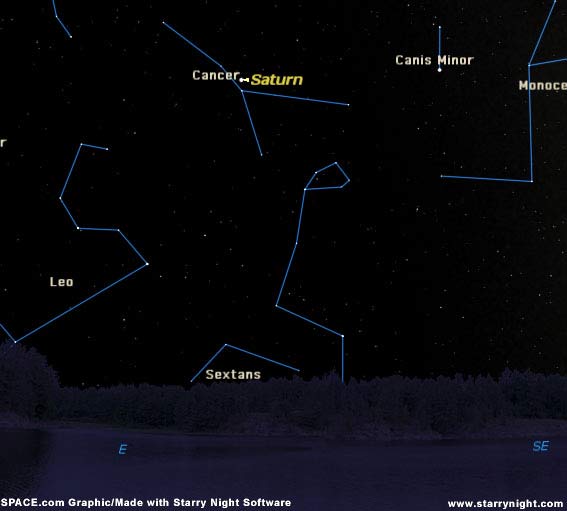

About halfway up in the east-southeast sky around 9 p.m. local time these frosty winter nights is the brilliant planet Saturn. This week, the ringed world is at its brightest for 2006, reaching a magnitude of -0.2.

Among the stars, only Sirius and Canopus are brighter.

Jan. 27 marks the night that Saturn arrives at opposition to the Sun; rising in the east as the Sun sets, peaking high in the south at midnight and setting in the west at sunrise.

Without a question Saturn's famous rings make it the telescopic showpiece of the night sky. In small telescopes, they always surprise observers, both novice and veteran alike, with their striking beauty. Any telescope magnifying more than 30-power will show them quite well.

Although visually they appear solid, the rings actually consist of countless billions of particles-chiefly consisting of water ice-ranging in size from icebergs to microscopic flecks. The rings are currently tilted at an inclination of 19 degrees toward the Earth. This will slowly increase in the coming weeks, ultimately reaching a maximum inclination of 20.2 degrees by the beginning of April.

You should take full advantage of this circumstance, because we won't see the rings tipped 20 degrees or more to our line of sight again until the year 2014!

Saturn is currently shining within the dim constellation of Cancer, the Crab. Cancer is the least conspicuous of the 12 zodiacal constellations. Aside from being in the Zodiac, it is probably only noteworthy because it contains one of the brightest galactic star clusters in the sky. Currently it appears only about a degree to the upper right of Saturn, appearing to the eye as a misty patch of light. But binoculars will quickly reveal its stellar nature. It is Praesepe, better known as the Beehive Star Cluster, containing hundreds of small stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This week, Saturn will appear to be passing through the southern extremities of the cluster, and will be just 0.9 degrees south of it on Feb. 2.

Interestingly, the Beehive was also used in medieval times as a weather forecaster. It was one of the very few clusters that were mentioned in antiquity. Aratus (around 260 BC) and Hipparchus (about 130 BC) called it the "Little Mist" or "Little Cloud." But Aratus also noted that on those occasions when the sky was seemingly clear, but the Beehive was invisible, that this meant that a storm was approaching. Of course, we know today that prior to the arrival of any unsettled weather maker, high, thin cirrus clouds (composed of ice crystals) begin to appear in the sky. Such clouds are thin enough to only slightly dim the Sun, Moon and brighter stars, but apparently just opaque enough to hide a dim patch of light like the Beehive.

Now, however, it might be difficult to see the Beehive with the unaided eye whether the sky is clear or not because of its close proximity to Saturn.

Currently, Saturn appears to be looping backward or to the west among the background stars. This is known as retrograde motion and is an artifact of the Earth overtaking Saturn as both planets move in their respective orbits around the Sun. Eventually, this backward motion will be cancelled out and Saturn will appear to come to halt and resume its normal eastward course. When its retrograde motion ends on April 5, Saturn will be poised a few degrees to the west of the cluster. Then, on June 5, Saturn will pass the Beehive again, slipping about 0.8º to the south of the cluster.

But anyone who trains binoculars on Saturn during the balance of the winter and on into the spring, will be able to get a fine view of both the solar systems' ringed wonder and this celestial weather forecaster.

Basic Sky Guides

- Full Moon Fever

- Astrophotography 101

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- 10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

- Understanding the Ecliptic and the Zodiac

- False Dawn: All about the Zodiacal Light

- Reading Weather in the Sun, Moon and Stars

- How and Why the Night Sky Changes with the Seasons

- Night Sky Main Page: More Skywatching News & Features

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

| DEFINITIONS |

1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance from the Sun to Earth, or about 93 million miles. Magnitude is the standard by which astronomers measure the apparent brightness of objects that appear in the sky. The lower the number, the brighter the object. The brightest stars in the sky are categorized as zero or first magnitude. Negative magnitudes are reserved for the most brilliant objects: the brightest star is Sirius (-1.4); the full Moon is -12.7; the Sun is -26.7. The faintest stars visible under dark skies are around +6. Degrees measure apparent sizes of objects or distances in the sky, as seen from our vantage point. The Moon is one-half degree in width. The width of your fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees. The distance from the horizon to the overhead point (called the zenith) is equal to 90 degrees. Declination is the angular distance measured in degrees, of a celestial body north or south of the celestial equator. If, for an example, a certain star is said to have a declination of +20 degrees, it is located 20 degrees north of the celestial equator. Declination is to a celestial globe as latitude is to a terrestrial globe. Arc seconds are sometimes used to define the measurement of a sky object's angular diameter. One degree is equal to 60 arc minutes. One arc minute is equal to 60 arc seconds. The Moon appears (on average), one half-degree across, or 30 arc minutes, or 1800 arc seconds. If the disk of Mars is 20 arc seconds across, we can also say that it is 1/90 the apparent width of the Moon (since 1800 divided by 20 equals 90). |

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.