See it Now: New Comet Brightens Rapidly

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

During the next couple of weeks skywatchers will be turning their attention to a newly discovered comet that has just swept past the Sun and will soon cruise past Earth on its way back out toward the depths of the outer solar system.

Astronomers, who attempt to forecast the future characteristics and behavior of these cosmic vagabonds, have found this new object to be a better-than-average performer.

The comet is now visible with a simple pair of binoculars, and it's also dimly visible to the naked eye if you know precisely where to look.

The discovery

The first word about this new comet (catalogued as C/2006 A1) came from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Cambridge, Massachusetts, which serves as the clearinghouse in the United States for astronomical discoveries. The SAO also serves in that capacity as an agency of the International Astronomical Union.

On Jan. 2, Grzegorz Pojmanski at the Warsaw University Astronomical Observatory discovered a faint comet on a photograph that was taken on New Year's Day from the Las Campanas Observatory in La Serena, Chile, as part of the All Sky Automated Survey (ASAS). A confirmation photograph was taken on Jan. 4. Later a prediscovery image of the comet dating back to Dec. 29, 2005 was also found.

Interestingly, about seven hours after Pojmanski detected the comet, another astronomer, Dr. Kazimieras Cernis at the Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astronomy at Vilnius, Lithuania, spotted it on ultraviolet images taken a few days earlier from the SOHO satellite. Despite this, however, the comet bears only Pojmanski's name.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Getting closer

A preliminary orbit for the new comet was quickly calculated. At the time of its discovery, the comet was about 113 million miles (181 million kilometers) from the Sun. But orbital elements indicated that on Feb. 22 it would be passing closest to the Sun (called "perihelion") at a distance of 51.6 million miles-not quite half the Earth's average distance from the Sun.

At the time of its discovery, the comet shone at a feeble magnitude of roughly 11 to 12, which is about 100 times dimmer than the faintest stars that can be perceived with the unaided eye. In addition, Comet Pojmanski was buried in the deep southern part of the sky, among the stars of the constellation of Indus (the Indian), and accessible only to observers in the Southern Hemisphere.

But since its discovery, the comet has steadily been progressing on a northward path.

Finally, the comet is becoming poised for visibility for Northern Hemisphere skywatchers, and it is expected to put on its best showing during the last days of February and the first week of March in the dawn morning sky.

What to expect

Preliminary predictions indicated that the comet would dutifully brighten as it approached the Sun. At perihelion, the most optimistic forecasts had Comet Pojmanski attaining a magnitude of +6.5 (generally considered the threshold of naked-eye visibility).

The comet had other plans, however, and has been increasing in brightness at a much faster pace.

On Feb. 7, Andrew Pearce, observing from Nedlands in Western Australia, caught the comet already shining at magnitude +6.4. "This comet appears to be brightening rapidly," noted Mr. Pearce, adding that a faint tail was also becoming visible. Twelve days later, the comet had brightened nearly a full magnitude, according to Mr. Pearce, reaching +5.4. On February 20, Luis Mansilla at the Canopus Observatory in Rosario, Argentina was able to see the comet in 7x50 binoculars despite interference from the Moon and haze near the horizon. He estimated its brightness at +5.3.

Currently, Comet Pojmanski is shining at around magnitude 5, which is roughly about the same brightness as the faintest star in the bowl of the Little Dipper. Sharp-eyed observers in a dark, clear sky can actually glimpse it without any optical aid.

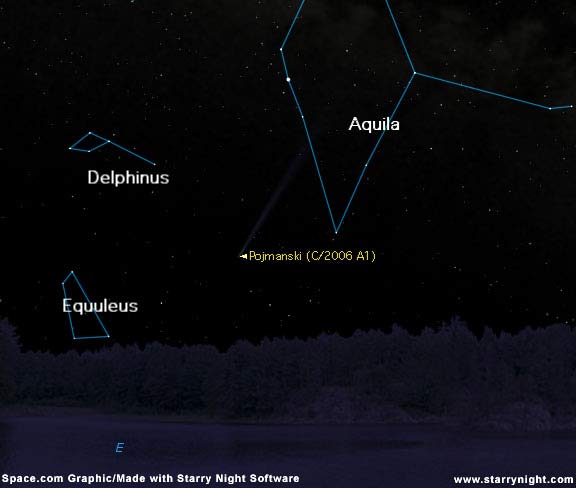

The comet is located in the zodiacal constellation of Capricornus, the Sea Goat. Beginning Feb. 27, skywatchers in the Northern Hemisphere can try locating it, very low above the horizon, somewhat south of due east about 90 minutes before sunrise. You can use Venus as a guide on this morning: the comet will be situated roughly 7 degrees to the left and slightly below the brilliant planet (the width of your fist held at arm's length and projected against the sky is roughly equal to 10 degrees).

As viewed from midnorthern latitudes, Comet Pojmanski will be positioned a little higher above the horizon each morning at the start of morning twilight. While it's only 5 degrees high on Feb. 27, this quickly improves to 10 degrees by March 2; 16 degrees by March 5 and 22 degrees (more than "two fists" up from the horizon) by March 9.

What you can see

In the early morning sky it can be readily picked up in binoculars looking like a small, circular patch of light with a bluish-white hue and an almost star-like center.

The comet will passing closest to Earth on March 5, when it be 71.7 million miles (115.4 million kilometers) away.

In small telescopes the comet's gaseous head or "coma" should appear roughly 1/6 of the Moon's apparent diameter as seen from Earth (an actual linear diameter of 209,000 miles or 335,000 kilometers). It will also likely display a short, faint narrow tail composed chiefly of ionized gases.

Well-known comet expert, John E. Bortle of Stormville, New York compares the view of Comet Pojmanski to that of an "apple on a stick; typical of dust-poor comets."

After March 5, the comet will be receding from both the Sun and Earth and rapidly fade as it heads back out into space, beyond the limits of the outer solar system.

Basic Sky Guides

- Full Moon Fever

- Astrophotography 101

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- 10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

- Understanding the Ecliptic and the Zodiac

- False Dawn: All about the Zodiacal Light

- Reading Weather in the Sun, Moon and Stars

- How and Why the Night Sky Changes with the Seasons

- Night Sky Main Page: More Skywatching News & Features

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

| DEFINITIONS |

1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance from the Sun to Earth, or about 93 million miles. Magnitude is the standard by which astronomers measure the apparent brightness of objects that appear in the sky. The lower the number, the brighter the object. The brightest stars in the sky are categorized as zero or first magnitude. Negative magnitudes are reserved for the most brilliant objects: the brightest star is Sirius (-1.4); the full Moon is -12.7; the Sun is -26.7. The faintest stars visible under dark skies are around +6. Degrees measure apparent sizes of objects or distances in the sky, as seen from our vantage point. The Moon is one-half degree in width. The width of your fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees. The distance from the horizon to the overhead point (called the zenith) is equal to 90 degrees. Declination is the angular distance measured in degrees, of a celestial body north or south of the celestial equator. If, for an example, a certain star is said to have a declination of +20 degrees, it is located 20 degrees north of the celestial equator. Declination is to a celestial globe as latitude is to a terrestrial globe. Arc seconds are sometimes used to define the measurement of a sky object's angular diameter. One degree is equal to 60 arc minutes. One arc minute is equal to 60 arc seconds. The Moon appears (on average), one half-degree across, or 30 arc minutes, or 1800 arc seconds. If the disk of Mars is 20 arc seconds across, we can also say that it is 1/90 the apparent width of the Moon (since 1800 divided by 20 equals 90). |

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.