Week-Long Meteor Shower to Dazzle

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The annual Geminid meteor shower is expected to produce a reliable shooting star show that will get going Sunday and peak the middle of next week.

The Geminid event is known for producing one or two meteors every minute during the peak for viewers with dark skies willing to brave chilly nights.

If the Geminid Meteor Shower occurred during a warmer month, it would be as familiar to most people as the famous August Perseids. Indeed, a night all snuggled-up in a sleeping bag under the stars is an attractive proposition in summer. But it's hard to imagine anything more bone chilling than lying on the ground in mid-December for several hours at night.

But if you are willing to bundle up, late next Wednesday night into early Thursday morning will be when the Geminids are predicted to be at their peak.

Most satisfying shower

The Geminids are a very fine winter shower, and usually the most satisfying of all the annual showers, even surpassing the Perseids. Studies of past displays show that this shower has a reputation for being rich both in slow, bright, graceful meteors and fireballs as well as faint meteors, with relatively fewer objects of medium brightness. Many appear yellowish in hue. Some even appear to form jagged or divided paths.

Unfortunately, as was the case this year with its summertime counterpart, this year's December Geminids will be hindered somewhat by moonlight, although to a much lesser degree than the brilliant gibbous Moon that wreaked havoc with the Perseids.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Thursday morning, the Moon-a fat waning crescent, two days past last quarter-will come up over the east-southeast horizon by 1:30 a.m. for most locations and will light up the sky in its general vicinity through the rest of the overnight hours. On Friday morning, the Moon will come up about an hour later and will be less of a factor for meteor watching.

Where to look

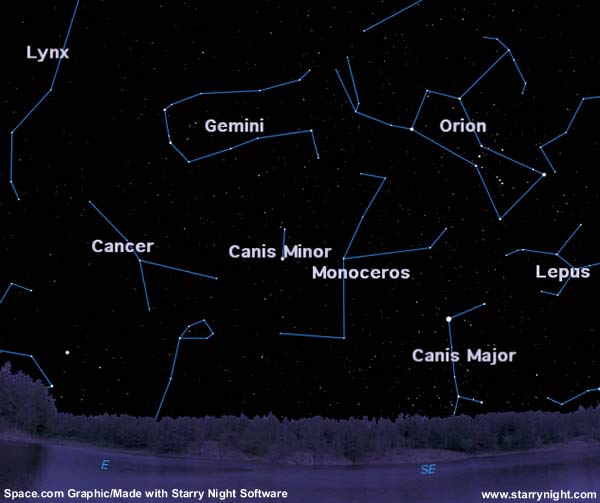

These medium speed meteors appear to emanate from near the bright star Castor, in the constellation of Gemini, the Twins, hence the name "Geminid."

The track of each one does not necessarily begin near Castor, nor even in the constellation Gemini, but it always turns out that the path of a Geminid extended backward passes through a tiny region of sky about 0.2-degree in diameter (an effect of perspective). In apparent size, that's less than half the width of the Moon. As such, this is a rather sharply defined radiant as most meteor showers go; suggesting the stream is "young"-perhaps only several thousand years old.

Generally speaking, depending on your location, Castor begins to come up above the east-northeast horizon right around the time evening twilight is coming to an end [sky map].

As Gemini is beginning to climb the eastern sky just after darkness falls, there is a fair chance of perhaps catching sight of some "Earth-grazing" meteors. Earthgrazers are long, bright shooting stars that streak overhead from a point near to even just below the horizon. Such meteors are so distinctive because they follow long paths nearly parallel to our atmosphere. By around 9 p.m., Gemini will have climbed more than one-third of the way up from the horizon. Meteor sightings should begin to increase noticeably thereafter. By around 2 a.m., Gemini will stand high overhead.

Because Geminid meteoroids are several times denser than the cometary dust flakes that supply most meteor showers and because of their relatively slow speed with which they encounter Earth (22 miles/35 kilometers per second), Geminid Meteors appear to linger a bit longer in view than most. As compared to an Orionid or Leonid meteor that can whiz across your line of sight in less than a second, a Geminid meteor moves only about half as fast.

On a personal note, their movement reminds me of field mice scooting from one part of the sky to another.

When to watch

The Earth moves quickly through this meteor stream producing a somewhat broad, lopsided activity profile. Hourly rates will start increasing on Sunday night (Dec. 10), appearing roughly above one-quarter peak strength.

Late Wednesday night up until early Thursday morning when the Moon rises, a single observer might average as many as 60 to 120 meteors per hour.

After Wednesday night, the rates are expected to drop off more sharply: The rates on Thursday night/Friday morning will have diminished to about 30 to 60 per hour. Yet, there is good reason to keep watching for Geminids even after their peak has passed, for those "late" Geminids, tend to be especially bright. And renegade late stragglers might be seen for a week or more after the night of maximum activity.

I brought this up this point earlier, but certainly it should be addressed again: Make sure you're warm and comfortable. Likely your local weather will be more appropriate for taking in a hot bath as opposed to a meteor shower! Warm cocoa or coffee can take the edge off the chill, as well as provide a slight stimulus.

A final point to note are that Geminids stand apart from the other meteor showers in that they seem to have been spawned not by a comet, but by 3200 Phaeton, an Earth-crossing asteroid. Then again, the Geminids may be comet debris after all, for some astronomers consider Phaeton to really be the dead nucleus of a burned-out comet that somehow got trapped into an unusually tight orbit.

- 2006 Leonid Meteor Shower Was a Bust

- Meteors and Meteor Showers: How They Work

- Does Anyone Ever Get Hit by Meteors?

- Tips on Meteor Shower Photography

- All About Meteors

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.