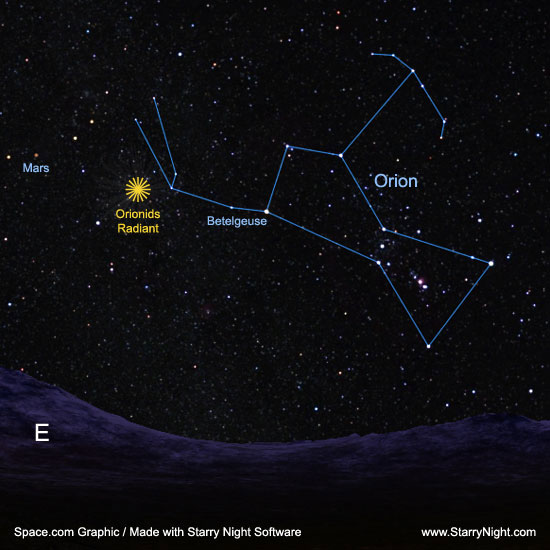

A junior version of the famous Perseid meteor shower isscheduled to reach its maximum before sunrise on Sunday morning, Oct. 21. Thismeteor display is known as the Orionids because the meteors seem to fan outfrom a region to the north of Orion's second brightest star, ruddy Betelgeuse.

Weather permitting and under very dark skies away from lightpollution, skywatchers could see several meteorsper hour. Rates will be significantly lower in cities and suburban areas.

Interestingly, this year, brilliant Mars is nearby and theapparent source of these meteors, called the radiant, will be positionedroughly between Mars and Betelgeuse.

When and where to watch

Currently, Orion appears ahead of us in our journey aroundthe Sun, and has not completely risen above the eastern horizon until after11:00 p.m. local daylight time. Expect to see few, if any Orionids beforemidnight – especially this year, with a bright waxing gibbous Moon glaring highin the western sky.

But moonset is around 1:30 a.m. local daylight time onSunday, and that's a good time to begin preparing for your meteor vigil. At itsbest several hours later, at around 5:00 a.m. when Orion is highest in the sky towardthe south, Orionids typically produce around 20 to 25 meteors per hour under aclear, dark sky.

"Orionid meteors are normally dim and not well seenfrom urban locations," said meteor expert Robert Lunsford, adding, ".. . it is highly suggested that you find a safe rural location to see the bestOrionid activity."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

According to Lunsford, Orionid activity has been increasingnoticeably since Oct. 17 when they were appearing at roughly five per hour indark-sky conditions. After peaking on Sunday morning, activity will begin toslowly descend, dropping back to around five per hour around Oct. 26. The laststragglers usually appear sometime in early to mid Nov.

Halley's Legacy

In studying the orbits of many meteor swarms, astronomershave found that they correspond closely to the orbits of known comets. TheOrionids are thought to result from the orbit of Halley's Comet;some of the dust which has shaken loose from this famous object as it runs itsgigantic loop from the Sun out to Neptune, ram our atmosphere to create theeffect of these "shooting stars."

There are actually two points along Halley's path where itcomes relatively near to our orbit.

One of these points corresponds to early May and causes ameteor display that emanates from the constellation Aquarius, the WaterCarrier. The other point lies near the late October part of our orbit andproduces the Orionids. In May we meet the "river of rubble" shed bythe comet on their way outward from their nearest approach to the Sun, while inOctober we encounter the part of the meteor stream moving inward toward theSun. The meteors are moving through space opposite or contrary to our orbitaldirection of motion. That explains why both the Aquarids and the Orionids hitour atmosphere very swiftly at 41 miles (66 kilometers) per second – only theNovember Leonids move faster.

Another distinguishing characteristic that the OctoberOrionids share with the May Aquarids is that they start burning up very high inour atmosphere, possibly because they are composed of lightweight material.This means they likely come from Halley's diffuse surface and not its core.

What to expect

Last year,there was an unexpected surprise when the Orionids put on a display more worthyof the Perseids. Observers saw meteors falling at double the normal rate, or 40to 50 per hour. In addition, many Orionids were much brighter than normal; afew even rivaled Venus in brilliance.

Two meteor researchers, MikayaSato and Jun-ichi Watanabe of Japan's National Astronomical Observatory,recently announced in a paper released by the Astronomical Society of Japanthat the unusual concentration of large particles that produced last yearsOrionids, were probably ejected from Halley's Comet almost 3,000 years ago andare being held together by interactions with Jupiter about every 71-years.

Apparently, there may also havebeen unusual Orionid activity during the years 1933 through 1938, so perhapsafter an absence of seven decades this concentration of comet material hasreturned, implying another rich Orionid display might be in offing this year.

The only way to know is to step outside just before thebreak of dawn on the morning of Oct. 21 (try the mornings of Oct. 20 and 22 aswell). Almost certainly, you should sight at least a few of these offspring ofHalley's Comet as they streak across the sky.

- Online Sky Maps and More

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- Astrophotography 101

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and otherpublications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.