People in the eastern United States will get a great opportunity, weather permitting, to see the Space Shuttle Discovery launched into orbit Wednesday evening.

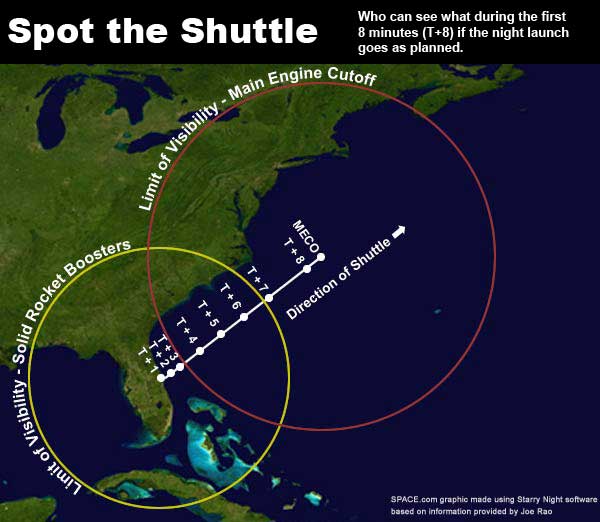

The shuttle flight (STS-119) will be the 28th to rendezvous and dock with the International Space Station (ISS), and the glow of its engines will be visible along much of the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. A SPACE.com map shows the area of visibility.

To reach the ISS, Discovery must be launched when Earth's rotation carries the launch pad into the plane of the station's orbit. For mission STS-119, that will happen at 9:20:10 p.m. ET on Wednesday, resulting in NASA's second consecutive nighttime launch (the most recent coming on Nov. 14).

As has been the case with other launches to the ISS, this upcoming launch will bring the shuttle's path nearly parallel to the U.S. East Coast.

What to expect

In the Southeast United States, depending on a viewer's distance from Cape Canaveral, the "stack" (shuttle orbiter, external tank and solid rocket boosters) can be easily followed thanks to the fiery output of the solid rocket boosters. The brilliant light emitted by the two solid rocket boosters will be visible for the first 2 minutes and 4 seconds of the launch out to a radius of some 520 statute miles from the Kennedy Space Center.

Depending on where you are located relative to Cape Canaveral, Discovery will become visible anywhere from a few seconds to just over 2 minutes after it leaves Pad 39-A.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For an example of what all this looks like from Florida, see video of a night launch made by Rob Haas from Titusville, FL, on Dec. 9, 2006 (the STS-116 mission).

After the solid rocket boosters are jettisoned, Discovery will be visible for most locations by virtue of the light emanating from its three main engines. It should appear as a very bright, pulsating, fast-moving star, shining with a yellowish-orange glow. Based on previous night missions, the brightness should be at least equal to magnitude -2; rivaling Sirius, the brightest star in brilliance. Observers who train binoculars on the shuttle should be able to see its tiny V-shaped contrail.

James E. Byrd shot video of the shuttle from Virginia after a November 2000 night launch. The bright star Sirius briefly streaks through the scene giving a sense of scale and brightness to the shuttle's glow.

For most viewers, the shuttle will appear to literally skim the horizon, so be sure there are no buildings or trees to obstruct your view.

Depending upon your distance from the coastline, the shuttle will be relatively low on the horizon (5 to 15 degrees; your fist on an outstretched arm covers about 10 degrees of sky). If you're positioned near the edge of a viewing circle, the shuttle will barely come above the horizon and could be obscured by low clouds or haze.

If the weather is clear the shuttle should be easy to see. It will appear to move very fast; much faster than an orbiting satellite due to its near orbital velocity at low altitudes (30-60 mi). It basically travels across 90 degrees of azimuth in less than a minute.

Discovery will seem to "flicker," then abruptly wink-out 8 minutes and 23 seconds after launch as the main engines shut-down and the huge, orange, external tank (ET) is jettisoned over the Atlantic at a point about 870 statute miles uprange (to the northeast) of Cape Canaveral and some 430 statute miles southeast of New York City. At that moment, Discovery will have risen to an altitude of 341,600 feet (64.7 statute miles), while moving at 17,579 mph and should be visible for a radius of about 770 statute miles from the point of Main Engine Cut Off (MECO).

Following MECO and ET separation, faint bursts of light caused by reaction control system (RCS) burns might be glimpsed along the now-invisible shuttle trajectory; they are fired to build up the separation distance of the orbiter from the ET and to correct Discovery's flight attitude and direction.

Lastly: before hoping to see the shuttle streak across your local sky, make sure it has left the launch pad!

What happens in case of a scrub?

Because Russia plans to launch a Soyuz spacecraft carrying the next space station commander and flight engineer on Mar. 26, the docked phase of the shuttle mission must be done by then to avoid a conflict. To get in a full-duration four-spacewalk mission, Discovery must take off by Mar. 13. Should the launch be postponed to Mar. 12, liftoff would come at 8:54 p.m. EDT; on Mar. 13, it would come at 8:32 p.m.

By giving up one or two of the mission's planned spacewalks, along with off-duty time, Discovery could launch as late as Mar 16 or 17 in a worst-case scenario. But that would coincide with bright twilight or sunset for parts of the Eastern Seaboard.

After that, the flight would slip to April 7, which would make it a daytime launch.

- Video: Night Shuttle Launch

- Gallery: 20 Great Rocket Launches

- Space Shuttle: Complete Launch Coverage

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.