Huge Asteroid Pallas Visible From Earth

This week, the huge asteroid Pallas reaches opposition,being opposite to the sun in Earth?s sky, making it a prime target for avidskywatchers with telescopes.

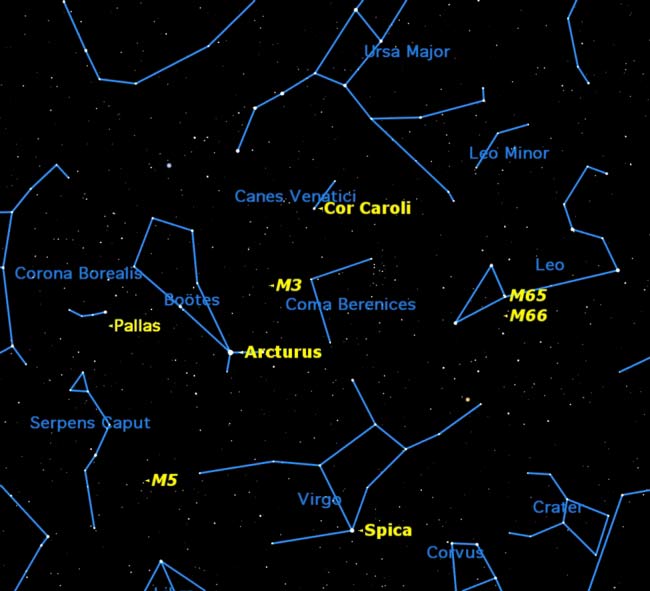

Asteroidsare not as well behaved as planets, and their orbits are often far from theplane of the ecliptic. This is clearly the case with Pallas, because it reachesopposition in the unlikely constellation of Serpens Caput, very close to CoronaBorealis, the Northern Crown. This is a pretty circlet of stars just to theleft of Arcturus in northern hemisphere skies.

To spot Pallas tonight, look for the brightest star, calledeither Alphecca or Gemma, in Corona Borealis. Pallas is an 8th magnitude objectjust south of this star. [How to spot Pallas.]

If you make a sketch of the star field with binocularstonight and repeat this over the next few nights, you?ll clearly see which?star? is moving: This is the best way to identify an asteroid. Alternatively,use planetarium software to make a chart of the area of Corona Borealis andidentify Pallas from that. Binoculars or a small telescope are essential forspotting this faint object.

Pallas is the second largest asteroid, 326 miles (524 km)in diameter. Or is it? Vesta might dispute this claim for, although it?sslightly smaller in diameter at 318 miles (512 km), it is much more massive dueto a much higher density.

Legacyof Pallas

Pallas' history is closely tied with the discovery of thefirst known asteroids centuries ago.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the year 1800, the solar system was a pretty simpleplace. There was the newly discovered planet Uranus, making a total of sevenplanets, plus the sun, moon, and a number of comets.

Within a few years, thesolar system became a much more complicated place. On the first day of thenew century, January 1, 1801, Giuseppe Piazzi discovered a new ?planet? whichhe named Ceres. A little over a year later, on March 28, 1802, Heinrich Olbersdiscovered another new ?planet? which he named Pallas after Pallas Athena,another name for the goddess Athena.

Olbers is most famous for his paradox, which states thatthe darkness of the night sky conflicts with the supposition of an infinite andeternal static universe.

These discoveries were followed by Juno in 1804 and Vestain 1807, the latter also being discovered by Olbers.

Astronomers were divided as to whether these tiny objectswere planets or something different, called ?asteroids? by some because theywere all so small that they appeared as stars in the telescopes of the day. Itwas nearly four decades before a fifth asteroid was found.

That find was almost totally overshadowed by the discoverya year later of the planetNeptune, and asteroids have been relegated to a minor role in the solarsystem ever since. We now know thousands of them, but the four discovered inthe first decade of the 19th century remain the largest and brightest.

Othertantalizing sky targets

While you?re out looking for Pallas, take the time to lookfor some deep sky objects. May and June are the months to hunt down galaxiesbut here are a couple of easier targets to start with, the globularclusters Messier 3 and Messier 5, both of which are well placed right nowand make fine sights in a small telescope.

Messier 3 is the easiest to find, about half way betweenthe bright star Arcturus and Cor Caroli, the smallish star all by itself tuckedunder the handle of the Big Dipper. Get your scope pointed at the right spotusing your finder, then sweep the area with your low power eyepiece until youspot a ball of fuzz. That's what it will look like at first, but when youswitch to a more powerful eyepiece, you'll see that it is actually a swarm oftiny stars.

Messier 5 is a bit trickier to find because it's in an areawithout many bright stars to guide you. Use Arcturus and Spica as your guides,the two brightest spring stars. You find them by extending the arc of thehandle of the Big Dipper: "Arc to Arcturus, then speed on to Spica."

Make an imaginary equilateral triangle with Arcturus andSpica as two of the corners, then imagine the third corner to their lower left,and sweep in that area with your low power eyepiece until you spot M5, whichlooks a lot like M3. These are two of the finest globular clusters in the sky,each with at least a hundred thousand stars in them.

Once you've located these two clusters, you might try for acouple of galaxies. Messier 65 and 66 in Leo are among the brightest galaxiesin the sky.

They are tucked just under the right angled triangle whichforms the left half of the constellation Leo. In fact they are just below thestar that marks the right angle. Look for two faint smudges of gray in your lowpower eyepiece.

Finding deep sky objects is much easier if you use a goodstar atlas and a pair of 7x50 or 10x50 binoculars to scout out the locationsfirst.

A dark clear sky is another essential: deep sky huntingcan't be done under suburban skies until you really know what you?re lookingfor. I recommend Sky & Telescope's Pocket Sky Atlas (Sky) and TerenceDickinson's book NightWatch (Firefly) as guidebooks.

- Images? Asteroids in Space

- StunningViews of Messier Objects

- More NightSky Features from Starry Night Education

This article was provided to SPACE.com by Starry Night Education, theleader in space science curriculum solutions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.