For skywatchers looking up after nightfall on Sunday or Monday (Jan. 9 or 10), you'll be able to see a thickening crescent moon pass well to the north of the brilliant planet Jupiter.

On Sunday evening, look toward the western sky and you'll see the moon with Jupiter shining about 7 degrees to its upper left. Your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees, so the distance separating Jupiter and the moon will measure almost three-quarters of a fist.

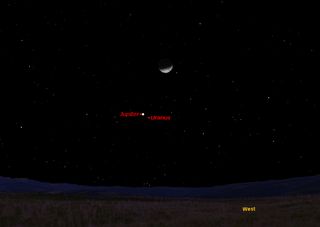

This sky map shows how Jupiter, the moon and Uranus will appear in the western sky on Sunday. A small telescope or binoculars are recommended when trying to observe Uranus, but Jupiter and the moon should be easily visible to the unaided eye, weather permitting

On Monday night, the moon will have moved to a position high above and to the right of Jupiter as shown in this sky map for Jan 10.

Both the moon and Jupiter will be in a fine position to look at with binoculars or a telescope during the early evening hours, but as the evening wears on, Jupiter will descend the western sky, ultimately setting at around 10:30 p.m. local time. Your best views of it will probably be between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m. local time.

The fat crescent moon might show signs of Earthshine – sunlight reflected off the Earth and directed toward the moon.

That sunlight reflected off of our planet causes the part of the moon not illuminated by the sun to glow a dim grayish-blue color and imparts an almost three-dimensional effect. The sight is especially striking in binoculars or through a low-power telescope.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If you train binoculars or a telescope on Jupiter, you'll get a view of the famous Galilean satellites, discovered by Galileo with his crude spyglass in 1610.

On Sunday, two of the moons (Ganymede and Io) will be on one side of Jupiter, while a third satellite (Callisto) will be on the other side. A fourth satellite (Europa) will be crossing in front of Jupiter.

On Monday night, all four satellites will be gathered on one side of Jupiter, with Ganymede and Europa appearing rather close to each other, while Io will be closest to Jupiter and Callisto farthest.

And if you look a short distance to the west (right) of Jupiter with binoculars, you might notice a bluish-green "star" which in reality is another planet – Uranus.

But seeing Uranus without a telescope is extremely difficult. Only skywatchers with sharp eyes, pristine weather conditions and ultra-dark skies in rural locations would have a slim chance to spot Uranus with the unaided eye.

Jupiter and Uranus recently completed an unusual triple conjunction on Jan. 2, in which the two planets appeared to pass each other three times over the past six months. They are still relatively close to each other and you still have a chance to use Jupiter to guide you to the much dimmer Uranus, which is barely visible to the unaided eye and is about 1/2,000 as bright as Jupiter.

Keep in mind that Jupiter is currently 487 million miles from Earth, while Uranus is 1.9 billion miles away.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.