Full Moon to Dance With Pleiades Star Cluster

This story was updated at 6:09 p.m. ET.

An odd thing is going to happen onSunday (Nov. 21): Justbefore sunrise, the full moon will appear on the western horizon justbeneaththe Pleiades, the brightest star cluster in the entire night sky.

The Pleiades is a cluster of brightstars located in theconstellation Taurus about 410 light-years from the sun. Asthe brightest starcluster, the Pleiades is a showpiece in both binoculars and smalltelescopes.

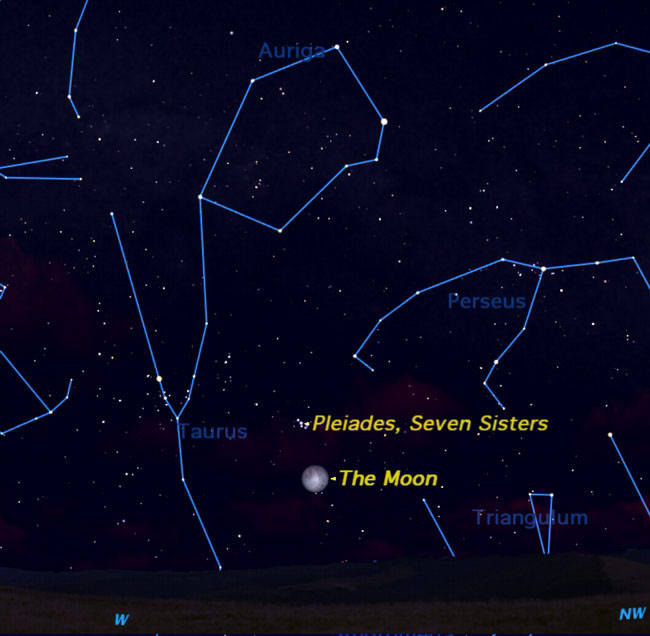

This sky mapshows how to spot the Pleiades alongwith the full moon on Sunday morning.

The morning sky show is just forstarters. The full moonand thePleiades will give an encore 12 hours later just aftersunset, when themoon will appear on the eastern horizon.

This is normal, and happens everymonth. But this time,the Pleiades is again immediately above the moon.

Thiswould seem to be impossible, because the moon moves steadily across thesky inits orbit around the Earth, and can?t be in the same place 12 hourslater. [Gallery- Full Moon Fever]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

How can it be?

Let's take a closer look at theimages of these two events:

First, look at the constellationsarrayed around the moonand the Pleiades, particularly Taurus, Auriga and Perseus. [Sky Maps: Nov.21 Moon at Sunrise, Moon at Sunset]

All three are present in bothimages, but theirorientation is completely different. Look closely at the Pleiadesthemselves,and you?ll see that they have flipped in 12 hours. So, what's going on?

There are two events that occurduring the day of Nov. 21that affect this month's full moon appearance.

First, full moon occurs at 12:27p.m. EST (1727 GMT).Technically, full moon is an instantaneous event:It happens at theprecise instant the sun, Earth and moon fall in a straight line.

At the time full moon occurs, theEarth is rotated so thatthe moon is below the horizon for observers in North America. So,neither ofthe moons in the two sky map images here is a truly full moon: thefirst is awaxing gibbous moon, about six hours short of full, and the second is awaninggibbous moon, six hours past full.

To the human eye, both look "full"so we tend tosay that both are full, even though this isn?t 100 percent accurate.

The other event that occurs is thatthe moon and thePleiades are in conjunction at 1 p.m. EST (1800 GMT). At this time, themoonand the Pleiades are as close as they can get this month, the moonbeing 1.3degrees south of the Pleiades.

This conjunction is not observablefrom the United States becausethe moon is below the horizon for North Americans.

Dancing with the Pleiades

Coming back to the sky maps, webegin to see what?s goingon. The moon has in fact moved from one side of the Pleiades to theother side,passing the Pleiades around just past noon while both moon and Pleiadesareunder our feet.

The radical change in theorientation of theconstellations is also a normal effect. If you watch any constellationover anentire night, you will see that it rises in the east in oneorientation, movesin a wide arc across the sky, and then sets about 12 hours later in acompletely different orientation.

Having the moon and the Pleiades asthe centerpiece inthis arrayof constellations gives us a point of reference, and itbecomes much easierto see how the constellations change their orientation from rising (asseen inthe sunrise sky map) to setting (as seen in the sunset sky map).

- Gallery- Full Moon Fever

- 10Coolest New Moon Discoveries

- BeginnerAstrophotography Telescopes

This article was providedto SPACE.com by StarryNight Education,the leader in space science curriculum solutions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.