Moonlight Meteor Shower Spawned By Halley's Comet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Ajunior version of the famous Perseid meteor shower thought to have originatedfrom the remains of Halley's Comet will hit its peak over the next week, butthe light of the moon may intrude on the sky show.

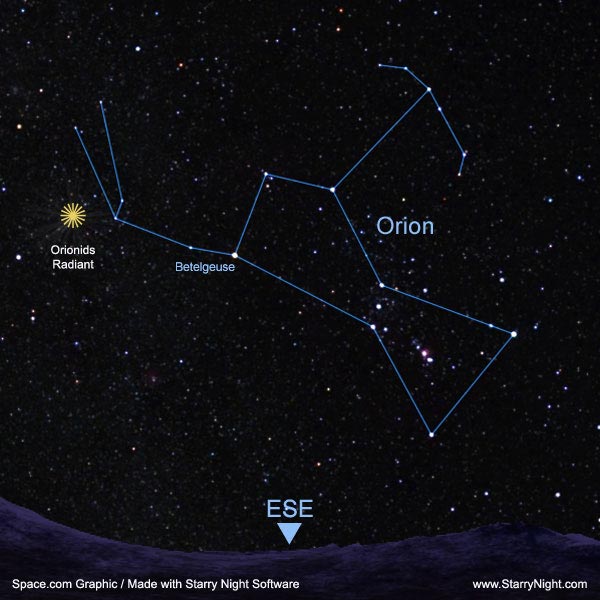

Thisupcoming meteor display is known as the Orionids because the meteors seem tofan out from a region to the north of the Orion constellation's secondbrightest star, ruddy Betelgeuse.

Theannual event peaks before sunrise on Thursday (Oct. 21) but several viewingopportunities arise before then for skywatchers in North America. [Where tolook to see the Orionids]

Theshooting stars are created by small bits of space dust— most no larger than sand grains — thought to be left overfrom the famed Halley's Comet, which orbits the sun once every 76 years.

Currently,Orion appears ahead of us in our journey around the sun, and has not completelyrisen above the eastern horizon until after 11 p.m. local daylight time.

Theconstellation is at its best several hours later. At around 5 a.m. –Orion will be highest in the sky toward the south – Orionids typicallyproduce around 20 to 30 meteors per hour under a clear, darksky.

But skywatchers beware: You will be facing a major obstaclein your attempt to observe this year’s Orionid performance. As bad luckwould have it, the moon will turn full on Oct. 23. Bright moonlight outshinesfainter meteors, seriously reducing the number anyone can see.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Thegradual build up to the full moon will hamper – if not outrightprevent – dark-sky observing during the Orionid meteor shower's peak onOct. 21.

TheOrionids are actually already underway, having been active only in a very weakand scattered form since about Oct. 2. But a noticeable upswing in activity isexpected to begin around Oct. 17, leading up to their peak night.

"Orionidmeteors are normally dim and not well seen from urban locations," notes meteor expert, Robert Lunsford, adding that "it is highlysuggested that you find a safe rural location to see the best Orionidactivity."

Damagecontrol for 2010

Withall this as a background, perhaps the best times to look this year will beduring the predawn hours several mornings before the night of full moon.That’s when the constellation Orion (from where the meteors get theirname) will stand high in the northeast sky.

Infact, three "windows" of dark skies will be available between moonsetand the first light of dawn on the mornings of Oct. 18, 19 and 20.

Generallyspeaking, there will be about 150 minutes of completely dark skies available onthe morning of the 18th.This shrinks to about 100 minutes on the 19th, and toabout 50 minutes by the morning of the 20th.

Thisskywatching tableshows prime Orionid meteor shower viewing times for some select U.S. cities.

In the table,all times are a.m. and are local daylight times. "Dawn" is thetime when morning (astronomical) twilight begins. A "Window" isthe number of minutes between the time of moonset and the start of twilight.

For example: When will the sky be dark and moonless for Orionid viewing on the morningof Oct. 20 from Houston?

Answer: There will be a 50-minute period of dark skies beginning at moonset (5:16a.m.) and continuing until dawn breaks (6:06 a.m.).

Perhapsup to a dozen forerunners of the main Orionid display might appear to steak bywithin an hour’s watch on these mornings, particularly on the 20th, themorning before the peak. It might even be worthwhile to try on Thursdaymorning, Oct. 21, although for most places, the moon will not set until justafter the first light of dawn.

Halley'slegacy

Instudying the orbits of many meteor swarms, astronomers have found that theycorrespond closely to the orbits of known comets.

TheOrionids are thought to result from the orbit of Halley's Comet, as some of thedust that has been shed by this famous object intersect earth’s orbitaround the sun during October.

Thereare actually two points along Halley’s path, where it comes relativelynear to our orbit. Another one of these points occurs in early May causing ameteor display from the constellation Aquarius, the Water Carrier.

Thetiny particles that are responsible for the Orionid and Aquarid meteors are– like Halley itself – moving through space in a direction oppositeto that the earth. This results in meteors that ram through ouratmosphere very swiftly at 41 miles (66 km) per second. Of all the meteordisplays, only the November Leonids movefaster.

Orionidpostmortem

Afterthe peak, activity will begin to slowly descend, although most of the meteorswill be squelched by the light of the moon. Rates drop back to around five perhour around Oct. 26. The last stragglers usually appear sometime around Nov. 7.

Itis indeed unfortunate that the Moon will likely obliterate most of the Orionidsin the nights following the peak, but the viewing odds will be much betterbefore the break of dawn on those mornings leading up to the peak. Almostcertainly, you should sight at least a few of these offspring of Halley's Cometas they streak across the sky.

Inthe absence of moonlight a single observer might see at least a couple of dozenmeteors per hour on the morning of the peak, a number that sadly can not behoped to be approached in 2010. In fact, it appears that this year, fans of theOrionids will be uttering the same lament that the old Dodger fans in Brooklynused to: "Wait till next year!"

- Images - The Best of Leonid Meteor Shower

- Video: Brilliant Fireball Over New Mexico Caught on Camera

- Lackluster Meteor Shower Sets Stage for Big Show in 2011

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.