This week, while the moon is still not overly bright, you have a chance to see the death of a star: a supernova. Unfortunately, this stupendous event is taking place not in our own galaxy — where it would be readily visible to the naked eye — but in the galaxy M101.

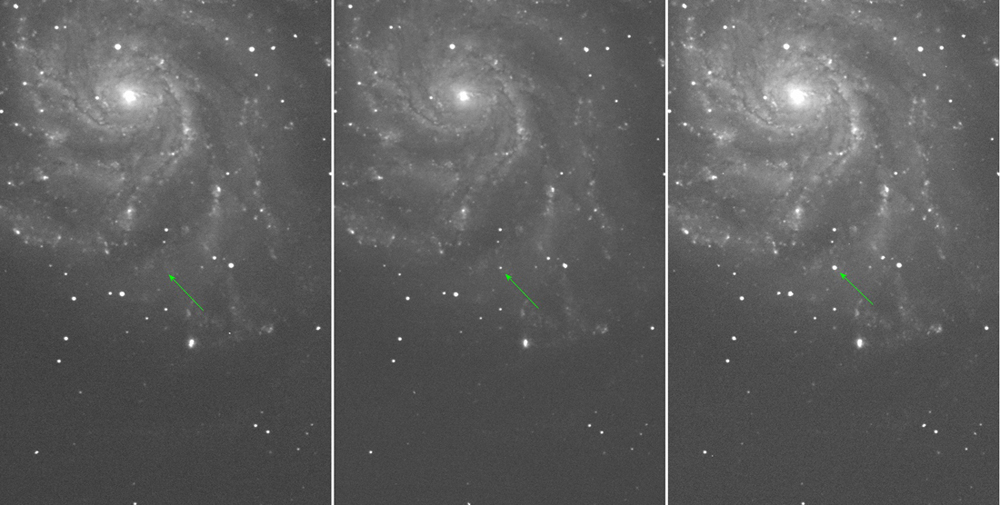

The bursting star was first seen on Aug. 23 with the 48-inch Oschin Schmidt telescope at Palomar Mountain Observatory in California. First called PTF 11kly and now designated SN2011fe, the supernova was discovered shining at a magnitude of +17.2, but has been brightening rapidly ever since.

Within the next week, it might reach 11th magnitude — appearing to shine some 300 times brighter than when it was first seen (remember, the lower the figure of magnitude, the brighter the object). The threshold of naked-eye visibility is magnitude 6.5.

Astronomers have categorized this catastrophic stellar explosion as a Type Ia supernova. A type Ia supernova occurs when a tiny white dwarf star acquires additional mass by siphoning matter away from a companion star. When it reaches a critical mass, the heat and pressure in the center of the star spark a runaway nuclear fusion reaction, and the white dwarf explodes.

Such explosions are spectacularly bright. For example: Placed beside the sun at a distance where the sun would appear as a star barely visible to the naked eye, a Type Ia supernova would appear to shine five times brighter than the full moon!

The galaxy in which this supernova is located, M101, has a linear diameter of more than 170,000 light-years, making it among the biggest disk galaxies known. And it is located at a distance of about 24 million light-years, meaning that the explosion actually took place 24 million years ago. It's taken that long for the light to get to us. [Photos of Great Supernova Explosions]

How to find it

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In his Celestial Handbook, Robert Burnham, Jr. describes M101 as "one of the finest examples of a large face-on Sc type spiral and a beautiful object on long-exposure photographs."

The Frenchman Pierre Mechain was the first to see this galaxy in 1781. Later that same year, it was observed by Charles Messier, who described it as appearing as "A nebula without star, very obscure and pretty large."

Messier would later include this galaxy as the 101st object in the final (1781) version of his famous catalog of comet masqueraders, hence "M" (for Messier) 101. It was one of the first "spiral nebulas" identified as such, in 1851 by William Parsons, the third Earl of Rosse.

Today, M101 sometimes goes by the popular moniker "The Pinwheel Galaxy." The name is quite appropriate, as observatory photographs show it as an impressive system with well-defined spiral arms. [Stunning Galaxy Photos from NASA's WISE Telescope]

It's also at a very convenient location, forming an equilateral triangle with the two end stars of the Big Dipper's handle, in the direction away from the Dipper's bowl. It's just 5 degrees east from the famous double star Mizar in the middle of the handle of the Big Dipper, and about the same distance east-northeast from Alkaid, the star that marks the end of the handle. Remember that your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees.

As darkness falls this week, the Big Dipper can be seen about halfway up in the northwest sky, with its handle pointing upward. By around 3 a.m. local daylight time, the handle is very low above the northern horizon. So if you want to see M101, your best bet is to try looking during the early evening hours while it's still reasonably high in the sky.

What to look for

M101's magnitude is listed as +7.7, which is only about three times dimmer than the threshold of naked-eye visibility. But while it may seem that this galaxy would be relatively easy to see in a telescope or even binoculars, it should be stressed that it's a rather challenging object to spot because of its great size and relatively low surface brightness. It is best seen under a very dark sky.

Inexperienced observers should be careful not to use too high a magnification with their telescopes. Faint and extended luminous objects are often evident only because of their contrast against the sky background.

In their book "Binocular Astronomy" (Willmann-Bell, Inc, 1992), authors Craig Crossen and Wil Tirion note that "as you look for M101, keep in mind that you are searching for an object with a diameter two-thirds the moon's, but with a surface brightness not much greater than the night sky itself."

Crossen and Tirion suggest using zoom binoculars at 12- to 15-power. A small telescope (4 to 6 inches at 30x) might show a smudge of light; a larger instrument (8 to 10 inches at 45x) may reveal a few brighter patches of light, while even larger scopes (12 to 16 inches at 60x) might start bringing out the galaxy's distinctive spiral structure. [Telescopes for Beginners]

And as for SN2011fe, it's located in the southwest (lower left) quadrant of M101. If you can find the galaxy's hazy patch, you just might also be able to discern the supernova as a tiny starlike speck of light within that area.

Are we overdue?

As a final note, three other supernovas have previously been seen in M101, in 1909, 1951 and 1970.

In contrast, in our own Milky Way galaxy, supernovas have been comparatively infrequent, the last three having been observed in 1054 (the remnants of which are the famous Crab Nebula), 1572 (extensively observed by Tycho Brahe and known as "Tycho's Star") and 1604 (extensively observed by Johannes Kepler and known as "Kepler's Star").

These three supernovas were dazzling objects, appearing for a time to rival Jupiter and even Venus. The fact that it has been more than 400 years since the last such flare-up in our own galaxy seems to suggest we are long overdue for another.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.