Northern skywatchers have passed the midpoint of winter, but there's still some time left to catch a glimpse of some of the best celestial sights the season has to offer.

So make the most of the remaining weeks of winter, I thought I'd compile what I’d consider to be the "Top 10" list of objects that are available during the early evening hours from now through early March. In fact … there are actually eleven objects on this wintertime list, with two double stars in a tie for ninth place!

Under a clear, crisp (and cold) winter sky, there are many objects that can be enjoyed with your unaided eye or binoculars or a small telescope. We'll assume that you're gazing skyward as soon as evening twilight has ended and complete darkness has fallen — roughly 90 minutes or so after sunset. Putting together a list of the best is, of course, very subjective. From your own nights of sky watching you may try compiling your own list and see if we agree on anything.

One other note: I'm not going to talk about any of the currently visible planets on this list, but for good reason: During February and March the five brightest ones will be readily visible during convenient evening hours and are highlighted separately in other SPACE.com skywatching features.

With that said, here's my take on the best skywatching targets for the winter season:

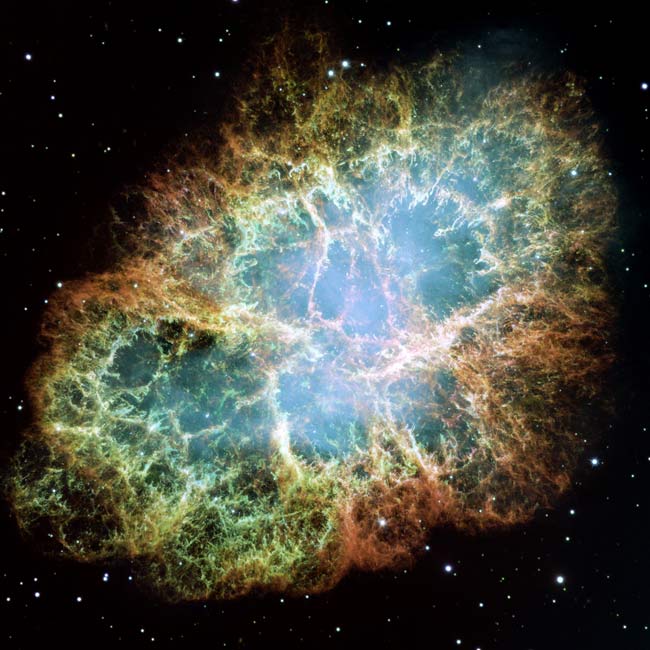

10) The Crab Nebula

In the year 1054 A.D. a brilliant new star suddenly appeared in the sky. Located within the horns of Taurus, the Bull, it initially seemed at least several times brighter than Venus and for 23 days was readily visible against a clear, blue daytime sky before it slowly began to fade. For a total of 653 days it could be seen with the naked eye, before it finally faded completely out of sight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Chinese called such a star a "guest star," because it visited for a while and then left. But this was an object that was far from being a new star. Rather it was a massive star that blew completely apart, leaving behind an expanding cloud of gaseous debris that we have come to know as the Crab nebula.

This object is now nearly overhead during the early evening hours, but a word of caution: you should also have access to a dark, clear sky, for at magnitude +8.4, the Crab unfortunately has a tendency to get lost in the background illumination in light polluted locations. It may be just barely visible as a dim patch of light in good binoculars. [Photos: 50 Amazing Deep-Space Nebulas]

The Crab nebula is more readily detectable in a 3-inch telescopeand begins to appear as irregularly oval-shaped with telescopes of 6-inch aperture or greater. It was, in fact, the Crab nebula's resemblance to a telescopic comet that prompted Messier to compile his celebrated catalogue of such fuzzy objects so that they might not deceive other comet hunters. The Crab nebula is first on his list and is therefore known as M (Messier) 1.

The moniker "Crab nebula" came about from an 1844 sketch of it made by the English astronomer, the third Earl of Rosse.

9) (Tie): Algeiba (The Lion’s Mane)

Now fully in view in the east-northeast sky is a harbinger of spring: the zodiacal constellation of Leo, the Lion. Especially noticeable is the backward question mark pattern of stars or "Sickle" that marks the head of the Lion.

Algeiba, also known as Gamma Leonis, is a second magnitude star in the curve or the blade of the Sickle of Leo. The name is derived from the Arabic Al Jabbah, meaning the mane of the Lion. It appears as a single star to the naked eye, however, as a telescope of only moderate size will clearly show; it is really one of the most beautiful double stars in the sky.

The magnitudes of the components are 2.3 and 3.5 and it should really be observed in twilight or bright moonlight to reveal the contrasting colors — one star has been said to be greenish, the other a delicate yellow. Others, however, have described different hues such as pale yellow and orange; reddish and golden yellow and even pale red and white! What do you see? Check them out in tonight's sky.

9) (Tie) Almach: Another Beautiful Double Star

While Leo, the Lion leads the retinue of spring stars emerging in the eastern sky, there are still some stars left over from the autumn season hovering over in the west.

Low in the west-northwest is the Great Square of Pegasus, the Flying Horse and extending upwards from the Square's upper left corner to a point roughly halfway from the horizon to the overhead point is a bright chain of stars representing Andromeda, the Princess. The end star of the chain (or the one farthest out from the Square) is called Almach. [12 Must-See Skywatching Events in 2012]

Also known as Gamma Andromedae, here is yet another beautifully colored double star — in fact, one of the finest — that can be easily separated with a small telescope. The brighter star (magnitude 2.3) appears golden yellow in color, perhaps ever so slightly tinged with orange, while the fainter companion (magnitude 5.4) appears distinctly bluish-green or aquamarine. The resulting contrast in colors is striking. Norton’s Star Atlas describes them as "Gold and blue; a magnificent object."

Interestingly, in the year 1842, astronomer Otto Struve discovered that the fainter companion star is itself a very close double, resolved only in large telescopes. Meanwhile, spectroscopic analysis has revealed that the brighter star is itself a binary star, thus making Almach a quadruple-star system!

8) Messier 35: A Superb Star Cluster

Soaring high in the east — almost to a point directly overhead — are the Gemini Twins, Pollux and Castor. They appear in the sky as two matchstick men holding hands.

Astronomer Henry Neeley (1879-1963), who was a popular lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium during the 1940s and 50s would often refer to the "long wedge" of Gemini, composed of the stars Pollux and Castor (the heads of the Twins) and Alhena which marks one of Pollux's feet. If you have binoculars, it is worthwhile to sweep the region of the sky from Alhena and points west to around the fainter stars Meboula and Propus.

Just above and to the right of Propus lies number 35 in Charles Messier's catalogue. Located just off the trailing foot of Castor, M35 can just be seen with the unaided eye on dark transparent nights. In low-power binoculars it may look like a dim, fairly large unresolved interstellar cloud, but look again.

Even through light-polluted suburban skies, 7x glasses reveal at least a half dozen of the cluster's brightest stars against the whitish glow of about 200 fainter ones. M35 has been described as a "splendid specimen" whose stars appear in curving rows, reminding one of the bursting of a skyrocket.

Walter Scott Houston (1912-1993) who wrote the Deep-Sky Wonders column in Sky & Telescope magazine for nearly half a century called M35: "… one of the greatest objects in the heavens. A superb object that appears as big as the moon and fills the eyepiece with a glitter of bright stars from center to edge."

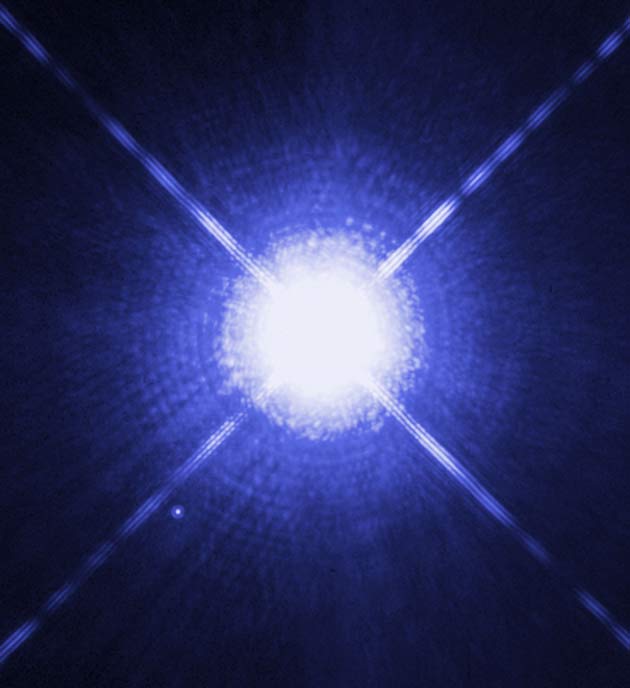

7) Sirius: The Winter Sparkler

Sirius, the Dog Star, is the brightest star of the constellation Canis Major, the "Greater Dog" in Latin. You simply can’t miss it: just cast a gaze toward the southeast part of the sky. According to Burnham’s Celestial Handbook other names for it include "The Sparkling One" or "The Scorching One."

The star appears a brilliant white with a tinge of blue, but when the air is unsteady, or when it is low to the horizon it seems to flicker and splinter with all the colors of the rainbow. At a distance of just 8.7 light-years, Sirius is the fifth-nearest known star. Among the naked-eye stars, it is the nearest of all, with the sole exception of Alpha Centauri.

Train a telescope on Sirius tonight and enjoy the beauty of this blue-white gem. Over thousands of years, Sirius appears to move in a wavy line across the sky. In 1862, Alvan G. Clark first saw Sirius B, also known as "the Pup," the companion star responsible for the wiggle. The Pup is a star of magnitude 8.5; only one ten-thousandth as bright as Sirius A.

The Pup pursues a 50-year orbit around Sirius A and is always a challenging object for amateur astronomers to see. The Pup is a strangely dense star known as a white dwarf. In fact, it packs 98 percent of one solar mass into a body just 2 percent of the sun’s diameter.

To do that, Sirius B must have a density 90,000 times that of the sun. A teaspoon of this star material would weigh about 2 tons.

6) The Beehive: Celestial Weather Forecaster

About halfway up in the eastern sky is the faintest of all the zodiacal constellations: Cancer, the Crab. For most sky watchers, this region of the sky seems nothing more than a dark and empty part of the sky. Sadly, the plague of light pollution is robbing us of our celestial heritage, and poor Cancer is one of the victims. Because it contains no star brighter than 4th magnitude, the crab is difficult, if not impossible to see under a light-polluted sky. [Photos: Light Pollution Hits Skywatching]

Cancer does have one significant attraction: appearing to the eye as merely a misty patch of light, binoculars will quickly reveal it as a beautiful open star cluster, containing hundreds of tiny stars. It is known to some as "Praesepe, the Manger." A manger is defined as “a trough in which feed for donkeys is placed." The cluster was apparently first called Praesepe 20 centuries ago. Indeed, two nearby stars, Gamma and Delta Cancri are also known as Asellus Borealis and Asellus Australis – the northern and southern ass colts – feeding from a manger.

The cluster also goes by the name "Beehive," a moniker that apparently evolved almost four centuries ago, when some anonymous person, upon seeing so many stars revealed in one of the first crude telescopes exclaimed: "It looks just like a swarm of bees!" Hence, the reason some astronomy books call it the Beehive cluster while others still call it Praesepe."

Interestingly, Praesepe was also used in medieval times as a weather forecaster. It was one of the very few clusters that were mentioned in antiquity. Aratus (around 260 B.C.) and Hipparchus (about 130 B.C.) called it the "Little Mist" or "Little Cloud."

But Aratus also noted that on those occasions when the sky was seemingly clear, but Praesepe was invisible, that this meant that a storm was approaching. Of course, we know today that prior to the arrival of any unsettled weather maker, high, thin cirrus clouds (composed of ice crystals) begin to appear in the sky.

Such clouds are thin enough to only slightly dim the sun, moon and brighter stars, but apparently just opaque enough to hide a dim patch of light like Praesepe.

5) The Double Cluster of Perseus

If you look high in the northwest, you’ll be able to see the zigzag row of five bright stars forming the constellation of Cassiopeia, the Queen.

If you extend an imaginary line roughly one and a half times the distance from the star Gamma to Delta Cass (also known as Ruchbah) and beyond, you'll come across a faint blur of light which binoculars will readily reveal as two magnificent clusters of stars. Popularly known simply as "The Double Cluster," it supposedly marks the location of the Sword Handle of Perseus, and one of the most brilliant telescopic sights in the sky.

NGC 869 and 884 (h Persei and Chi Persei respectively) are magnificent through binoculars or the low-power field of a small telescope; a pair of glorious open clusters, each of which would be beautiful by itself. The overall diameter of each cluster is about 45 arc minutes, or about one-third larger than the apparent diameter of the moon. So you should use very low powers to get both clusters together in the same field of view. Much higher powers will cause the star field to be spread-out and not as impressive. Close inspection with a good telescope will reveal a fine ruby-colored star near the center of 884.

Wrote Walter Scott Houston: "One can look for a long time at the many doubles, the colors, the winding patterns, as the dense cores of the cluster thin out slowly to merge finally in the star-rich background of the galaxy itself. Gazing at these clusters produces a succession of feelings too subtle and too complex to be captured by words alone."

4) The Hyades: The Angry Bull's Face

Due south and located nearly overhead is Taurus, the Bull. The Bull’s face is plainly marked by the fine V-shaped cluster of the Hyades.

Notice the bright red star at the end of the lower arm of the V, which represents the Bull’s fiery eye. That’s Aldebaran, "the follower." It rises soon after the Pleiades star cluster and pursues them across the sky.

The Hyades are among the nearest of star clusters, which explains why so many of the separate stars can be seen. At a distance of 130 light-years, the Hyades are moving in the general direction of the star Betelgeuse in Orion, while receding from us at the rate of 100,000 miles per hour.

Aldebaran, by the way, is not part of the Hyades but merely an "innocent bystander" because just happens to accidentally line up with the cluster to complete this perfect V in the sky.

It's a giant star, about 40 times the diameter of our sun, 125 times as luminous and 65 light-years away. Aldebaran is moving toward the south almost at right angles to the cluster’s motion and twice as fast. Taurus’s V-shaped face is, therefore, going to pieces. For 25,000 years more it will pass for a V, but after 50,000 years it will be quite out of shape.

3) The Pleiades: The Seven Sisters

Few star figures are as familiar as the Pleiades, also known as the Seven Sisters. Without a question of doubt, they are the most famous galactic star cluster in the entire sky. If you have any difficulty in recognizing various stars and constellations then you start with the Pleiades.

This group looks at first glance like a shimmering little cloud of light. But further examination will reveal a tight knot of 6 or 7 stars, though some with very acute eyesight have been able to see 11 or more under excellent sky conditions.

But for the very best effect, examine the Pleiades either through 7-power binoculars, or better yet, a small telescope magnifying 15 to 20-power with a wide field of view. In this manner, they will offer an almost indescribable sight.

About 250 stars have been identified as members of this cluster. Several stars in the cluster seem to be enveloped in clouds of dust, perhaps left over from the stuff which they were formed. About 410 light-years away and some 20 light-years across, the group may be no older than 20 million years.

The brightest stars glitter like an array of icy blue diamonds on black velvet. Or, as Tennyson wrote, in the opening passage of Locksley Hall, they "… glitter like a swarm of fireflies tangled in a silver braid."

2) The Great Andromeda Galaxy

During the 10th century, the Persian astronomer Al Sufi drew attention amidst the stars, which we now call Andromeda, the Princess to a "Little Cloud." Even today, binoculars and telescopes reveal that "cloud" as little more than an elongated fuzzy patch, which gradually brightens in the center to a star-like nucleus.

Andromeda is still about halfway up in the west-northwest sky, where you can seek out Al Sufi’s little cloud: a small hazy spot if the night is perfectly clear and moonless. It is, in fact, the most distant object that the human eye can see without any optical aid.

Please forgive this patch of light for being so faint and tired looking. You will when you realize that, as you see it now, this light has been traveling at least 2.2 million years to reach you, traveling all that time at the tremendous velocity of 671 million miles per hour. The light you are seeing is around 22,000 centuries old and began its journey around the time of the dawn of human consciousness.

When it began its nearly 13-quintillion-mile journey earthward, mastodons and saber-toothed tigers roamed over much of pre-ice-age North America and prehistoric man struggled for existence in what is now the Olduvai Gorge of East Africa. When you have finally located this "little cloud," it is hard to believe that it is actually made up of over 300 billion suns like the one we see every day: The Great Andromeda Galaxy.

It is so distant that only the telescope and camera combined can show its true nature. Long exposure photographs reveal it to be a whole universe of stars like our own galaxy.

1) The Great Orion Nebula

Orion, the mighty Hunter is now high toward the south by nightfall. Below Orion’s famous three-star belt is undoubtedly one of the most wonderfully beautiful objects in the sky: Messier 42, The Great Orion Nebula. [Photos: The Splendor of the Orion Nebula]

It appears to surround the middle star of a fainter trio of stars in a line that marks the hunter’s sword. It’s invisible to the unaided eye, though the star itself appears a bit fuzzy. It is resolved in good binoculars and small telescopes as a bright gray-green mist enveloping the star.

In larger telescopes it appears as a great glowing irregular, translucent fan-shaped cloud. A sort of auroral glow is induced in this nebula by fluorescence from the strong ultraviolet radiation of four hot stars entangled within it: Theta-one Orionis, better known as the Trapezium.

About a decade ago, at a star party held on a September night at Colbrook, Conn., I remember most of the participants waiting until nearly 3 a.m., when Orion finally cleared a local tree line to the east. Soon, long lines began assembling behind several large Dobsonian telescopes, all pointing toward the Great Nebula. As I patiently waited for my turn at the eyepiece, I heard this comment made from out of the darkness: "I would have packed it in an hour ago, but I wasn’t going to miss a view of M42!"

Edward Emerson Barnard (1857-1923), for many years an astronomer at Yerkes Observatory, once remarked that it reminded him of a great ghostly bat and that he always experienced a feeling of surprise when he saw it. William T. Olcott called it a "A glorious and wonderful sight … words fail utterly to describe its beauty."

The Great Orion Nebula is a vast cloud of extremely tenuous glowing gas and dust, approximately 1,600 light years away and about 30 light-years across (or more than 20,000 times the diameter of the entire Solar System). Astrophysicists now believe that this nebulous stuff is a stellar incubator; the primeval chaos from which star formation is presently underway.

Certainly, all you need do is take one look through a good telescope and you will see for yourself why this interstellar nursery is our choice as the number one sky object to look for on a clear, dark winter's night.

If you have an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.