Overlooked gravitational wave signals point to 'exotic' black hole scenarios

Revisiting their initial data, LIGO-Virgo Collaboration scientists discover 10 new black-hole mergers.

In a new analysis of their gravitational wave data, scientists with the international LIGO-Virgo Collaboration (LVC) have discovered 10 new examples of merging binary black holes.

Over the past seven years, the researchers have observed 90 gravitational wave signals — ripples in the space-time continuum that indicate "cataclysmic events" such as black hole mergers, the research team said in a statement. They originally detected 44 such mergers during a six-month observational period in 2019, but a second look at the data using a different methodology revealed 10 additional ones.

These newly detected black hole mergers suggest "exotic astrophysical scenarios" that can be studied only through the gravitational waves that emanate from them, the scientists behind the new detections argue.

Related: 8 ways we know that black holes really do exist

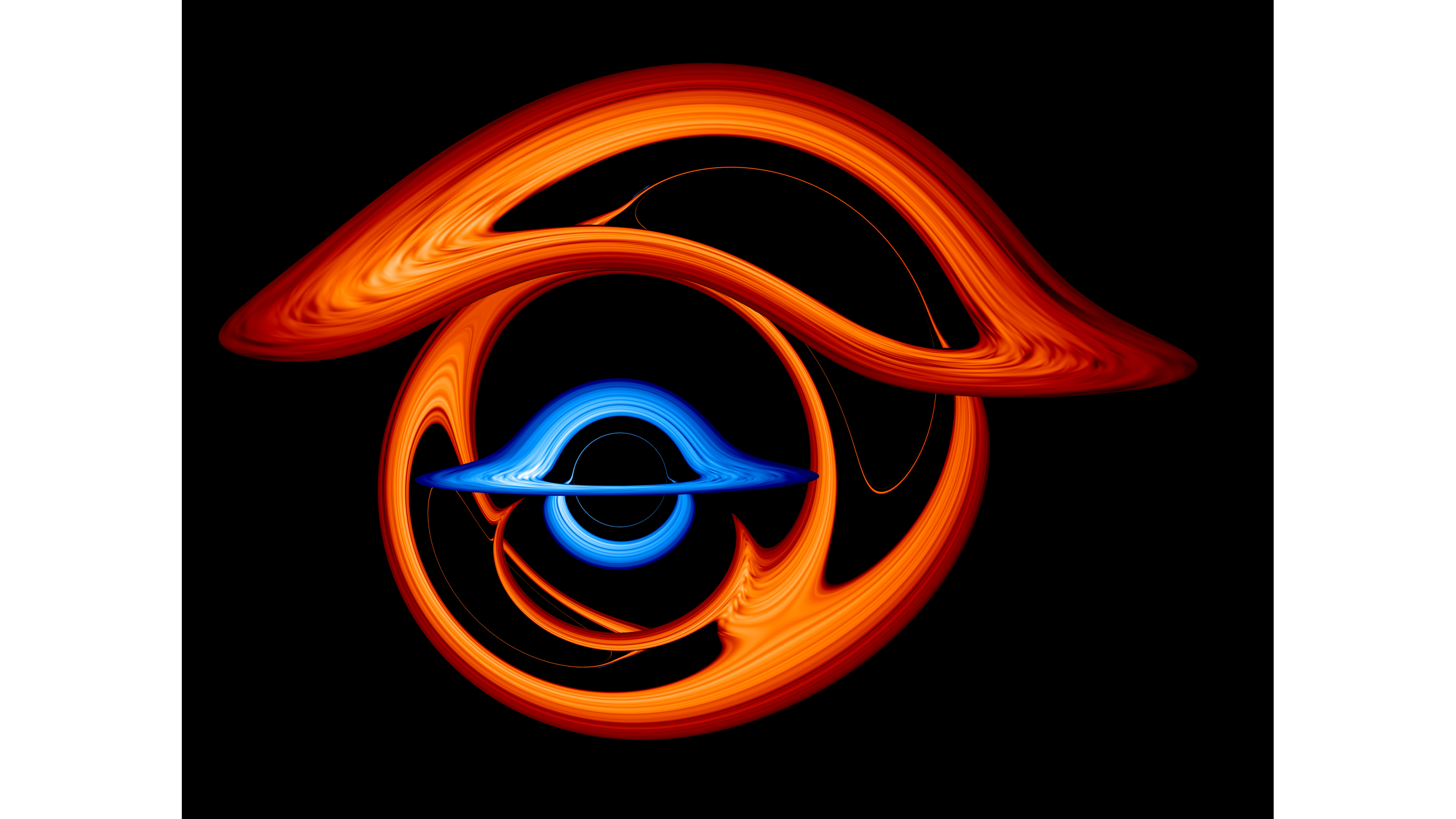

For instance, one of the mergers appears to be a never-before-observed type of system in which a heavy black hole is consuming a smaller black hole that had been orbiting it in the opposite direction of its own spin.

"The heavier black hole's spin isn't exactly anti-aligned with the orbit, but rather tilted somewhere between sideways and upside down, which tells us that this system may come from an interesting subpopulation of BBH [binary black hole] mergers where the angles between BBH orbits and the black hole spins are all random," Seth Olsen, a doctoral candidate in physics at Princeton University who led the reanalysis of the original observations, said in the statement.

The discovery of the new mergers fills gaps in existing black hole data, as some of the black holes have higher or lower masses than are predicted by widely accepted nuclear physics models, the researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When we find a black hole in this mass range, it tells us there's more to the story of how the system formed, since there is a good chance that an upper-mass-gap black hole is the product of a previous merger," Olsen said.

Olsen presented his team's findings at the American Physical Society's April meeting.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.