This story was updated at 2:28 p.m. ET.

SEATTLE – Researchers have mapped out mysterious dark matter in a sample of huge galaxies, determining where the strange stuff resides and how much of it there is.

Dark matter is thought to make up much of the universe but remains invisible to astronomers. Its existence is inferred by its gravitational effects, which can be measured.

Astronomers assembled the new map by studying how the faraway galaxies bend light thrown off from even more distant objects. The results could yield insights about galaxy formation as well as the nature of dark matter, researchers said.

"We don't know very much about [dark matter] at all," lead author David Pooley, of Eureka Scientific, Inc., told reporters here today (Jan. 13) at the 217th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. "To get any new information on dark matter, new information of any kind, is exciting."

Peering through a gravitational lens

Pooley and his team used NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory to study 14 massive elliptical galaxies, which are about 6 billion light-years from Earth on average. Each one sits almost directly in front of an even more distant galaxy, nearly three times farther away.

"These types of systems are relatively rare," Pooley told reporters today. "It takes a special configuration."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Each of the more distant galaxies harbors a quasar at its core. Quasars — active supermassive black holes that exude huge amounts of radiation — are some of the brightest objects in the universe.

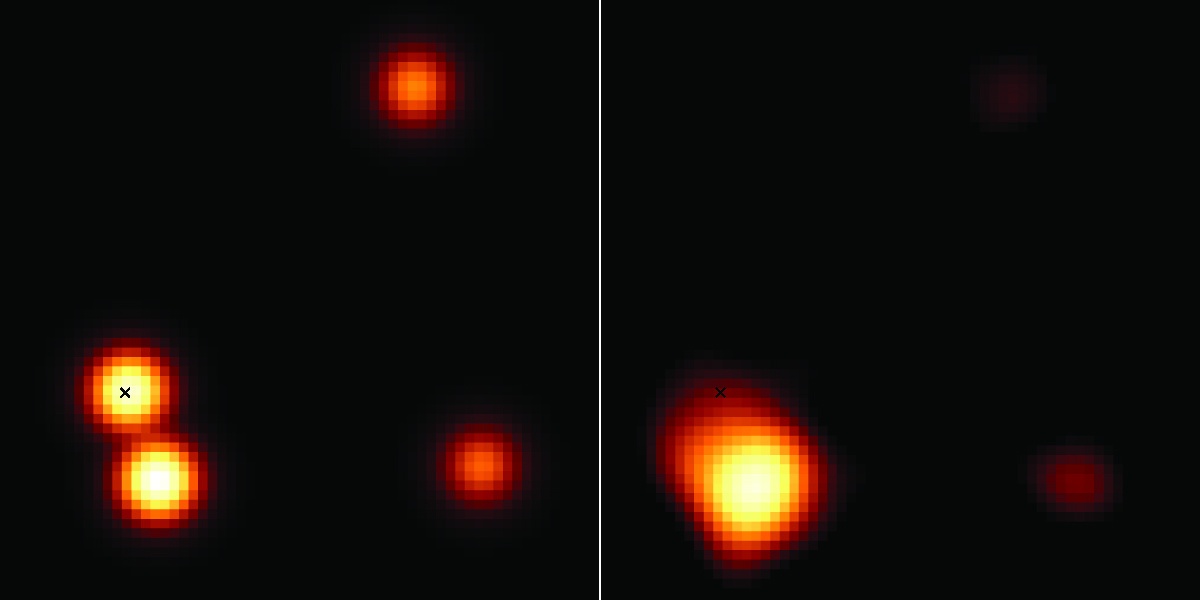

The huge gravity of the closer-in galaxies bends the quasars' light significantly. These intervening "gravitational lenses" thus produce four images of the background quasar as seen from Chandra's vantage point.

"We compared what those four images were supposed to look like according to lensing theory to what we actually saw with Chandra," Pooley said. "We found some major differences."

These differences are likely due to the makeup of the matter in the lensing galaxies, Pooley added.

Mapping out dark matter

Details of the lensing galaxies' composition — such as how many stars they possess, and how much dark matter is found in the locations where the light passes through — can affect the quasars' light, beyond simply generating four images.

Using modeling techniques, the researchers figured out that, to produce what Chandra saw, the lensing galaxies must consist of about 85 to 95 percent dark matter in the regions where the quasars' light passes through. [Video: Dark Matter in 3-D]

"This is definitely, by far, the most likely composition of these galaxies, to give us what we observe," Pooley said.

In general, those regions are located about 15,000 to 25,000 light-years from the centers of the lensing galaxies, similar to the distance of our solar system from the core of the Milky Way, researchers said.

Other studies have determined the amount of dark matter in clusters of galaxies, but the dark matter being studied has mostly been in the vast spaces between the galaxies, researchers said. The new study, on the other hand, takes a much finer view..

"We really are probing well inside these galaxies," Pooley said.

The researchers will refine their results further, as more gravitationally lensed quasars are discovered and then observed with Chandra. Such discoveries will be aided by large-area surveys by ground-based observatories, such as the Panoramic Survey Telescope & Rapid Response System project and the future Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, researchers said.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.