New Mars Missions to Focus on Search for Life

After more than four decades of humans sending robotic missions to the Red Planet, Mars science is entering a new phase, coinciding with the launch of NASA's Curiosity rover planned for this later this year, according to experts who spoke at a panel discussion last week.

"We are going to make this transition from following the water to seeking signs of life," Doug McCuistion, director of the Mars Exploration Program at NASA, told the audience at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Mars has gone through various geologic stages. In its first billion years, it is believed to have been wetter and more Earth-like. Then it experienced a period of volcanism, and today it is cold and dry, said panelist John Mustard of Brown University. It's not clear what happened to cause these changes, he said.

"If it was Earth-like, did life ever get a chance to get going and is there life there today?" he said.

Curiosity

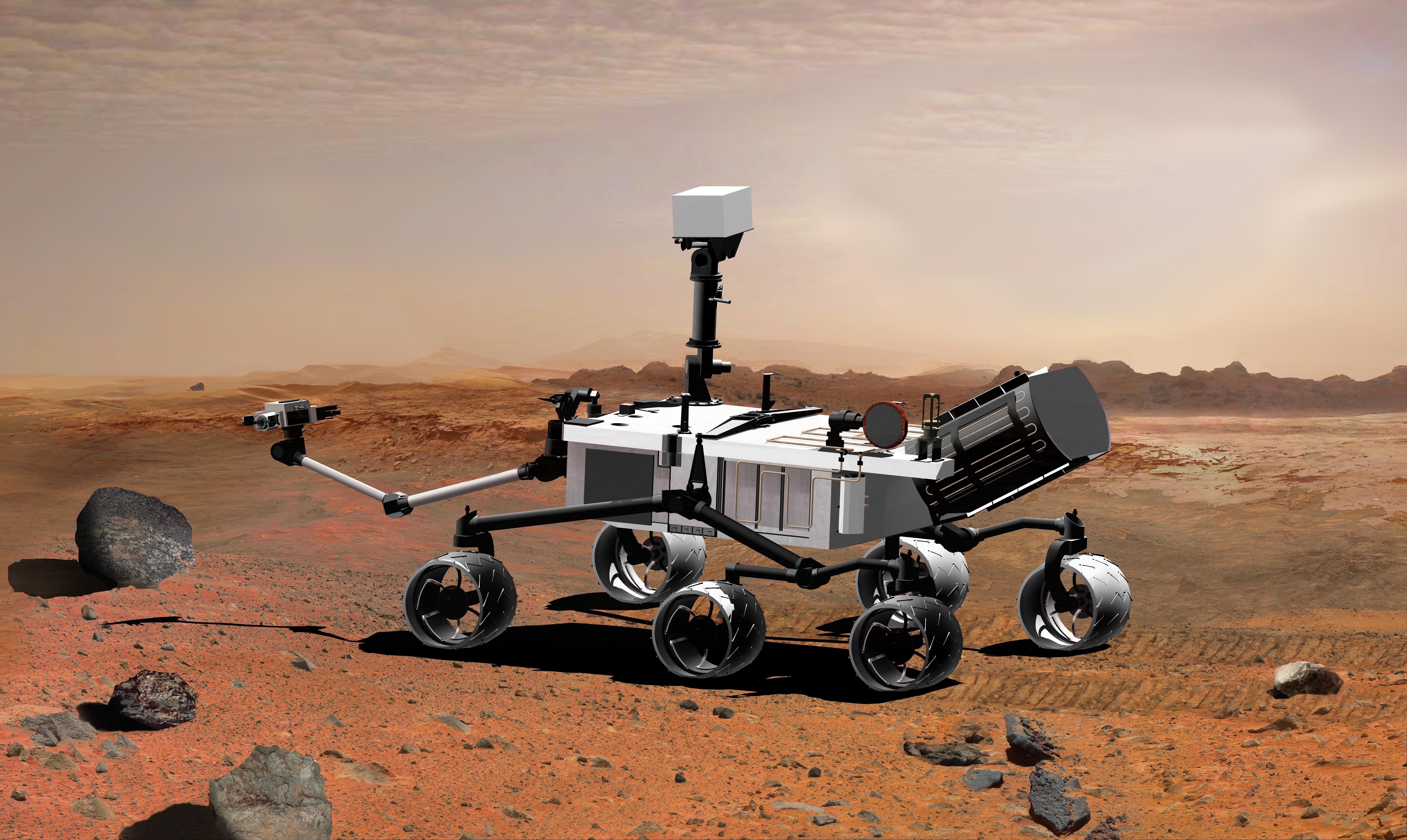

The upcoming Mars Science Laboratory mission is expected to deliver a new payload of scientific equipment to the surface of Mars in the form of the Curiosity rover. While NASA's two rovers currently on the surface, Spirit and Opportunity, each measure about five feet tall and six feet wide, Curiosity will be the size of a small car and carry more complex instrumentation, including an onboard chemistry lab, according to the panelists.

To determine if a particular area has samples worth collecting, Curiosity will have a "chemistry camera" which allows it to shoot a laser at a rock, creating plasma it can analyze before driving over, according to McCuistion.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"One of the key questions we are asking is, where are the organic molecules?" said Jennifer Eigenbrode, a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Just as larger organisms leave behind fossils, microorganisms can leave behind evidence of their existence. For instance, the lipids that make up membranes of a cell are complex molecules that contain carbon atoms bonded together, she said.

"Under certain conditions that carbon-carbon bond can be preserved," Eigenbrode said. "That's called a molecular fossil."

The instruments being taken to Mars include one tool that can detect molecular fossils from life as small as microorganisms, she said.

But finding organic molecules is not a sure sign of life. Organic molecules could have been deposited by meteorites, or created by geological processes. On top of that, the molecules may have been altered since being created, Eigenbrode said.

Curiosity will also study larger features in the rocks, including their appearance and structure, to create a complete package of information, she said.

What are we looking for?

Defining life is a tricky thing, and using a standard created to fit life on Earth has hazards, the scientists acknowledge. There are a common set of traits used to define life, according to Mary Voytek, who heads NASA's astrobiology program.

Life needs water, a particular set of elements, energy, a cell or structure to separate itself from its environment and a way to store and reproduce its blueprint and also convert those instructions into proteins. And the system as a whole must be able to respond to Darwinian evolution, she said.

Voytek said scientists have been thinking out of the box, asking, for instance, in what other solvents, besides water, could life grow?

The European Space Agency picked up evidence of one such potential solvent, methane, in 2003. Although it is produced by life on Earth, the gas can also be produced by geological processes.

In joint Mars missions beginning in 2016, the ESA and NASA plan to continue the search for methane, and to drill down a few meters into the Martian surface, looking for possible life forms, said Marcello Coradini, an ESA program coordinator.

Longer-term, the agencies hope to be able to bring rocks back from Mars for analysis on Earth, he said.

Beginning with NASA's Mariner 9 spacecraft in 1971, multiple orbiters have found evidence that liquid water once flowed on Mars.

"What we have been able to do is add layer upon layer of detail to our understanding of what the chemistry was like, what the environment was like," said Steven Squyres of Cornell University.

The four sites being considered as landing sites for Curiosity contain evidence that was water was present in them, including traces of ancient rivers.

Wynne Parry is a senior writer for LiveScience, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow her on Twitter @Wynne_Parry.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.