From Shuttles to Rockets: Long History for Calif. Launch Pad

Space shuttle astronaut extraordinaire Bob Crippen, member of the first crew and commander of three more, was poised to lead the maiden West Coast mission into polar orbit from Space Launch Complex 6 at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

Scheduled for the summer of 1986, the flight would usher in the Air Force space shuttle era, enabling large and valuable spy satellites to be carried into orbits around Earth's poles by the winged space planes.

And it would bring the Navy captain's space career back to the place where he originally planned to leave the planet for space.

Two decades earlier, that very site was the launch pad for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, a high-flying military reconnaissance space station.

But, remarkably, both projects were mothballed before Crippen ever got to blast off from the famed SLC-6 pad.

"The first time I heard of the space shuttle was in 1969. I was just coming off a program that had been cancelled, called the Manned Orbiting Laboratory," he says.

"Some of us crew were trying to go to work for NASA. We were discouraged at first, but George Mueller, who was (associate administrator) for spaceflight, directed Deke Slayton, who was head of all the astronauts, that he would take some of us. Deke reluctantly said 'hey, I got lots of work for you, but I'm not going to have anything for you to fly until the space shuttle, which might be 1980.' The shuttle wasn't even an approved program at that juncture."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Origins of the pad

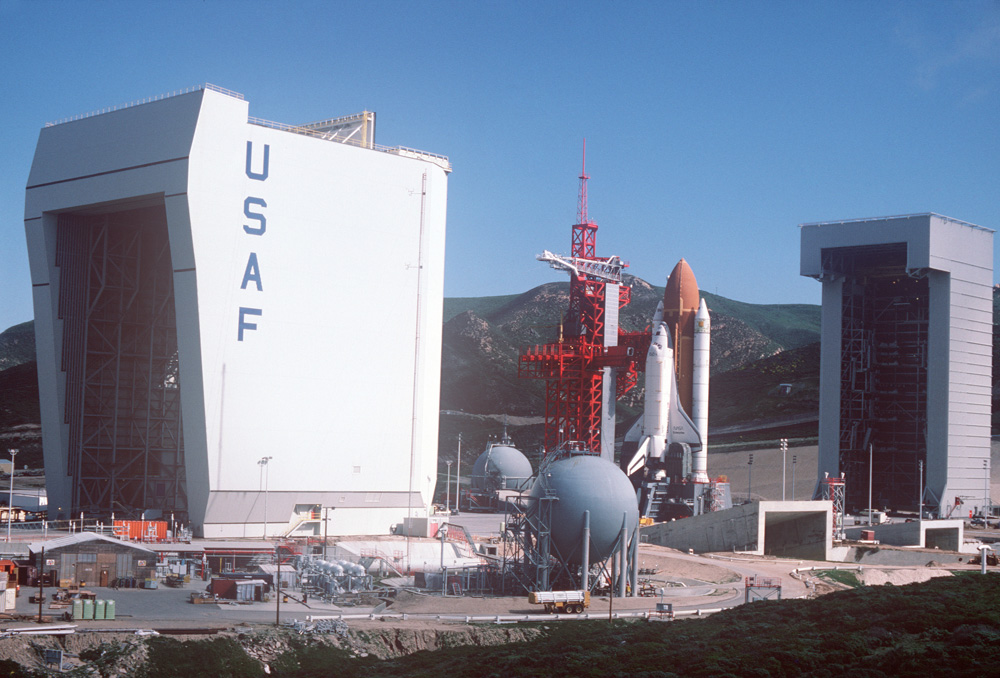

Space Launch Complex 6 had been built on the southern stretches of Vandenberg to fly Titan 3 boosters and modified Gemini B capsules with the Manned Orbiting Laboratory. Construction of the $3 billion pad started in March 1966.

But President Nixon would end the whole program three years later without fielding the MOL due to delays, cost overruns and the realization that unmanned satellites could better fulfill the nation's reconnaissance needs.

NASA picked up Crippen to join the civilian astronaut corps., pairing him with moonwalker John Young for the space shuttle's daring first mission. The Columbia roared into orbit on April 12, 1981 on a two-day shakedown cruise like no other.

Crippen would get to fly three times aboard the Challenger, launching in June 1983 with Sally Ride, America's first woman astronaut, overseeing the first rescue and repair of a satellite in space, the wayward Solar Max, in April 1984, and commanding a satellite-deploy and research mission in October 1984 that also featured spacewalking astronauts testing techniques for orbital refueling of spacecraft.

It was a distinguished spaceflight career, one that earned Crippen assignment as commander for the inaugural shuttle flight from the military's launch facility being constructed from the old mothballed SLC-6 pad at Vandenberg.

The Air Force base was perfect for launching shuttles southward over the open ocean to reach polar orbits, which are the destination for imaging and surveillance satellites. Getting to that type of orbit is impossible from Florida's Cape Canaveral because the shuttle would fly above populated land during ascent.

SLC-6 had been closed for a decade after MOL when machinery moved in and started a $4 billion overhaul that transformed the complex from the previous program to the new space shuttle's California home.

Enterprise, NASA's prototype orbiter, was brought to SLC-6 in early 1985 to check out the nearly-finished pad, offering a dramatic glimpse of what a space shuttle looked like standing atop the site.

Unlike shuttle infrastructure in Florida that stacked the vehicles at the Vehicle Assembly Building and rolled them three-and-a-half miles to the launch pad on Apollo-era transporters, the boosters, fuel tank and orbiter would be brought together on a stationary mount atop the California pad.

The payloads would be readied in ultra-clean rooms right at the pad and wheeled up to the shuttle bay. And the launch team would be stationed in a fortified control center inside the complex, too.

It was a twist on operations for the space shuttle, not to mention the aesthetics of the towering hillsides surrounding the pad and Vandenberg's trademark fog that were so different from Cape Canaveral's endless swamps and waterways.

Launching from the California base, Crippen's crew would become the first astronauts to experience the vantage point of polar orbit. They'd deploy the Teal Ruby experimental spacecraft and operate a package of sensors in the payload bay.

But as the West Coast shuttle site was being built, the program's overall viability as the nation's primary means of launching satellites was coming under serious doubt.

Questioning policy

The U.S. space policy since the time of the space shuttle's creation directed that all payloads, no matter whether they were commercial, civilian or military, go aboard the human-tended vehicles instead of unmanned rockets. Industrial production of the expendable boosters was being phased out as NASA promised frequent and affordable launches of payloads aboard the space shuttle.

However, the advertised capabilities used to build support for the space shuttle's development in the 1970s were not turning into reality once the vehicles actually entered service in the early 1980s.

Promises of flying 50 times per year were proving to be a laughable overestimation. The first years of flight revealed that there wouldn't be a simple ease of turning around a shuttle in between missions -- it would take months, not days.

Although construction continued at SLC-6, it was becoming obvious to the military that the winged machines would not live up to the hyped concepts.

The man calling the shots at the Pentagon was Edward "Pete" Aldridge, under secretary (later, the secretary) of the Air Force and director of the National Reconnaissance Office. He was responsible for coordinating space programs for the military and covert NRO, and he was convinced that the country couldn't put all of its proverbial eggs in the shuttle basket.

"When the realities of the shuttle performance became apparent in the early years of shuttle operations, around 1983, the DoD began to argue for a change in the shuttle-only policy to permit ELV production to continue until the shuttle completely demonstrates that it can meet the launch rate and payload demands of civil, commercial and DoD users," Aldridge recalls.

The projected number of Air Force and NRO space shuttle missions was 10 to 12 per year, which was more than the vehicles even were performing. NASA still hoped to get perhaps 24 launches conducted each year, but 1985 had just 9.

"As flight rates dropped, the cost-per-flight eliminated the projected cost advantage of the shuttle operations over ELVs, and pressure began to build to increase the price charged for each DoD flight," Aldridge said.

"I decided we ought to not terminate expendable launch vehicles... In '83, I went to the Secretary of Defense and said, 'I believe we should not terminate the production of expendable launch vehicles until the shuttle can prove itself, that it can fly at least 24 flights per year, and it can meet the performance demands of the Department of Defense, therefore we should keep a number of expendable launch vehicles continuing.'"

The DoD's plan called for building 10 large expendable rockets to launch national security satellites twice per year, and thus extend unmanned booster operations five more years.

"It was believed then that five additional years would clearly demonstrate whether the shuttle would meet demands of all the users," said Aldridge.

"After a lot of discussion, arguments, testimony before Congress and bureaucratic infighting, the shuttle-only policy was eventually overturned by President Reagan in 1985 and signed into a policy directive stating that the ELV complement to the shuttle would be developed."

To help sooth tensions between NASA and the Pentagon, a top-ranking military official would get to fly aboard the first Vandenberg shuttle mission. The man picked was none other than Pete Aldridge.

Aftermath of Challenger

The seven-man crew was in New Mexico training with one its payloads, a Sandia National Laboratories sensor, when they paused to watch the ill-fated Challenger launch on Jan. 28, 1986.

It was a day that forever changed the way the space shuttle was viewed and used.

"I guess like all things, you never forget exactly where you were and what you saw at the time," Aldridge said. "We saw it take off. Crippen was sitting in front. I was in the back of the room and I saw this explosion, and thought, Jesus. Then I was waiting for the orbiter, as we all were, to come out of the smoke. But as soon as that explosion occurred, Crippen obviously knew what it was. His head dropped. I remember this so distinctly. He knew exactly what happened. Or anticipated it much more so, I think, than the rest of us did."

That devastating event in America's space program would spell the end of Vandenberg ever hosting a shuttle mission. With the fleet grounded and the acknowledgement that the shuttles weren't going to supply the Pentagon with its space-lift needs, the stage was set for developing Titan 4 rockets to launch large satellites, the Atlas 2 for medium-class cargos and the Delta 2 to deploy the Global Positioning System.

"The new space launch policy was formulated, which directed only man-required payloads be flown on the shuttle and no commercial launches would be allowed," said Aldridge.

The original 1970s sales pitch that said the spaceplanes would launch every satellite the nation could build was over.

"Where man is not required, such as the DoD satellites, you don't expose men in that mission when it can be flown better off an expendable launch vehicle."

Immediately following the Challenger tragedy, work at SLC-6 slowed and then eventually stopped as the national decisions came into focus. With all the planned payloads switching to new rockets, the West Coast shuttle launch site received an official termination on December 26, 1989.

"Unfortunately, that Vandenberg flight never happened because of that accident. I really wish Pete had a chance to fly on the shuttle. I think he would have really appreciated (the shuttle), having seen it first hand," Crippen says.

Crippen also would never again fly in space, taking on management duties at NASA and in the commercial world before retiring.

"If I have one disappointment in my flight career, it's we did not get to make that polar orbit out of Vandenberg," he added.

The Atlas 2, Delta 2 and Titan 4 boosters were built and enjoyed many successful years of hoisting satellites to space.

The SLC-6 pad supported a handful of flights by Lockheed Martin's small Athena vehicle in the 1990s, the first rockets to finally launch from the site after the MOL and shuttle programs never got off the ground.

Then Boeing assumed control of the pad and shaped it into the home for the Delta 4 evolved expendable launch vehicles, the next-generation of modernized rockets that have replaced the ones Aldridge had advocated so strongly two decades ago.

Much of the structures from the shuttle-era at SLC-6 were put to use by Delta 4, as the uniqueness of that place lives on. Boeing launched a pair of medium-class rockets in 2006, then United Launch Alliance began upgrading the accommodations to support the nation's new heavy-lift vehicle that stepped up after the Titan 4 retired from duty.

And now, a quarter-century after Crippen and Aldridge were supposed to fly together from there, the mammoth Delta 4-Heavy is poised to launch from SLC-6 for the first time on January 20. The unmanned booster will carry a giant reconnaissance satellite that would have flown aboard a Vandenberg space shuttle, if history had taken a different route.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Justin Ray is the former editor of the space launch and news site Spaceflight Now, where he covered a wide range of missions by NASA, the U.S. military and space agencies around the world. Justin was space reporter for Florida Today and served as a public affairs intern with Space Launch Delta 45 at what is now the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station before joining the Spaceflight Now team. In 2017, Justin joined the United Launch Alliance team, a commercial launch service provider.