The dangers of human spaceflight will be on many people's minds during the next week as NASA and the nation commemorate three space tragedies.

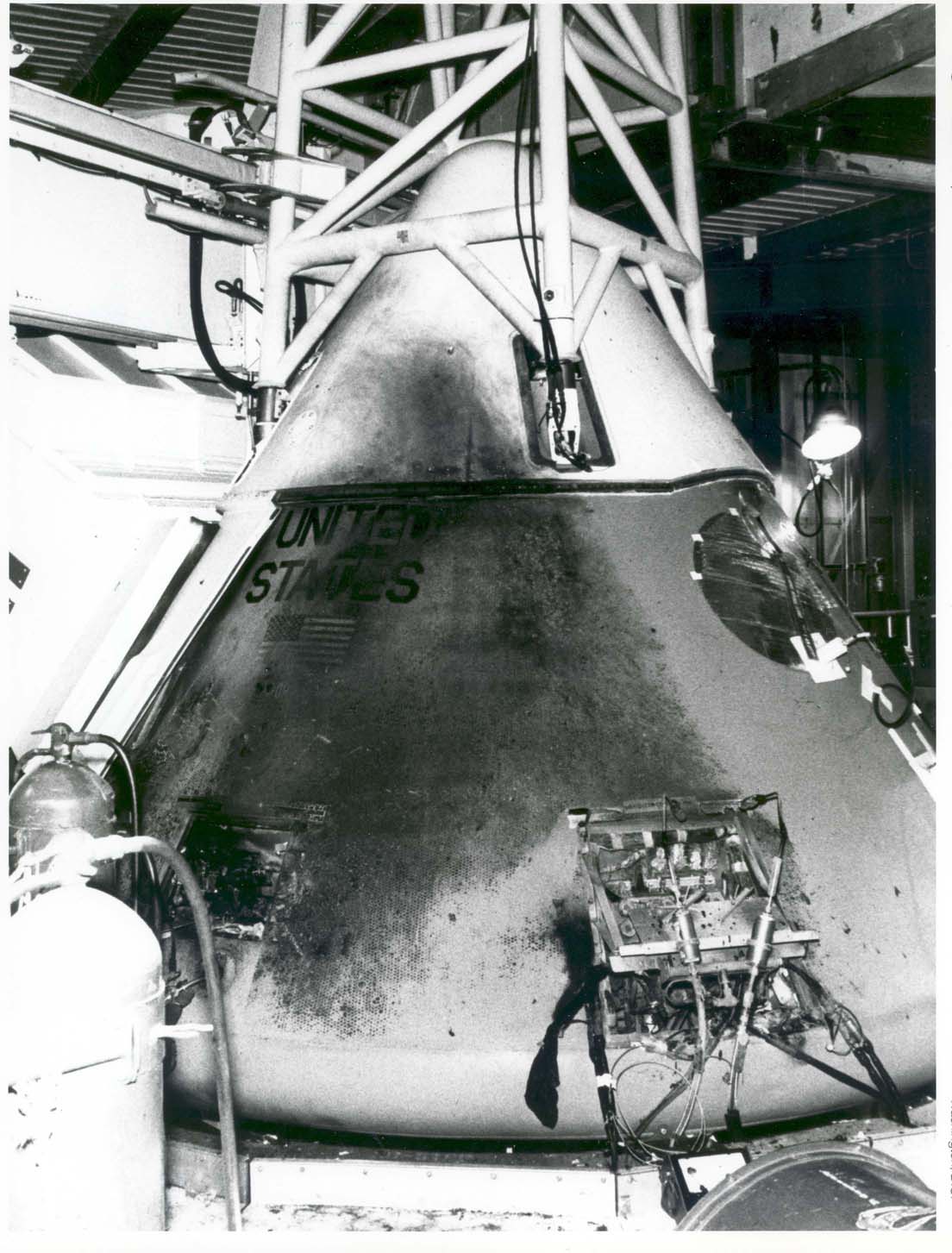

Twenty-five years ago on Friday (Jan. 28), the space shuttle Challenger broke apart less than two minutes after launch, killing all seven astronauts aboard. On Feb. 1, 2003, the shuttle Columbia and her seven-astronaut crew were lost during re-entry into Earth's atmosphere. And on Jan. 27, 1967, a fire during a ground test killed three astronauts preparing for the Apollo I mission.

These accidents reinforce the idea that sending humans to space is an inherently risky endeavor, and will continue to be risky for quite some time, experts say. Many factors conspire to make this so, including the extreme energies needed to reach Earth orbit and the inhospitable environment of space.

"We have to keep admitting that this is dangerous stuff, and we've got to treat it that way," Bryan O'Connor, head of NASA's Safety and Mission Assurance Office, told SPACE.com. "It's worth doing, if we have a good mission. But we can't underplay the risk of it." [Infographic: The Dangers of Human Spaceflight]

Human spaceflight: By the numbers

NASA has launched 132 manned shuttle missions in the 30 years of the space shuttle program. The agency has lost two of them — Challenger and Columbia.

Russia's Soyuz program has a similar failure rate, with two fatal accidents in just over 100 manned missions — though Soyuz hasn't had a fatality in nearly 40 years.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The shuttle and Soyuz risks are thus in the same ballpark as the chances of dying while trying to climb Mount Everest. From 1922 to 2006, one out of every 49 people who undertook the climb ended up dying, O'Connor said.

The risk takes on a whole new perspective when compared to the safety record of commercial aviation. In 2010, U.S. airlines did not have a single fatal accident, despite taking to the skies more than 10 million times and carrying about 700 million passengers.

The issues

Comparing a rocket-powered trip to low-Earth orbit with a redeye from San Francisco to Los Angeles isn't really fair, however — they're two completely different beasts.

Getting to space has traditionally required huge amounts of energy, which can be dangerous to produce. The space environment itself imposes other challenges for a spaceship and her crew, such as high levels of radiation and fast-moving orbital debris.

And getting back to the relatively friendly confines of Earth isn't easy, as re-entry generates extreme temperatures that can burn through a spacecraft's exterior.

"Launching humans into space is not easy," Bob Doremus, manager of safety for NASA's shuttle program, told SPACE.com. "And we've learned that over time through some very hard lessons in the shuttle program."

Practice, practice, practice

One big reason human spaceflight remains so risky is that it's so expensive, according to O'Connor.

In the aviation world, it's common to test-fly a new aircraft a few thousand times, to make sure everything works properly and all of the kinks get worked out, O'Connor said. But cost issues make such extensive flight testing pretty much impossible for spaceships, he added.

"In spaceflight, it's so expensive that we tend to start flying our missions very, very early in the development phase," O'Connor said. "We prove our system while we're doing our mission with it. We don't have the luxury of doing those in series."

That's true of the space shuttle, which first carried humans into space in 1981 and is set to retire later this year.

"I believe that the shuttle is still in a flight-test environment," O'Connor said. "It's not truly operational and probably never will be, even if we flew it another 10 to 15 years."

Flight tests are key in the emerging private space sector, too, according to Virgin Galactic CEO and president George Whitesides. Virgin Galactic plans to launch commercial tourist jaunts to suborbital space soon, perhaps in the next year or so.

Virgin Galactic's aims are quite different from those of NASA, so the safety issues and outlooks of the two entities aren't directly comparable. But the importance of practice is a common bond.

"The best thing to do is to fly," Whitesides told SPACE.com. "You can run as many models as you like, and over time those models will take on increasing levels of sophistication. But at the end of the day, it's flying a real vehicle that is the most important to improving the safety of the system."

Safety will improve over time

Like aviation, human spaceflight will get safer and safer as the years pass and knowledge grows, according to experts.

"Although it's always going to be fairly risky, the risk will get reduced with experience,"said John Logsdon, a space policy expert and professor emeritus at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Technological advances should also help, O'Connor said, noting that propulsion systems may become more reliable and structures more capable of withstanding the extreme loads spaceflight imposes.

Other safety breakthroughs could come in innovative spacecraft or mission design, especially if this design emphasizes simplicity, according to Logsdon. The idea is that the less complex a spaceship or rocket is, the fewer things can go wrong with it.

"The best path to reducing risk is to have a simple system," Logsdon told SPACE.com.

Whitesides agreed that simplicity is key. Simplicity is a chief design objective of Scaled Composites, the California company that built Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo,he added.

"I don't know if I'd call it a simple vehicle. It is, after all, a spaceship," Whitesides said. "But it is as simple as it can be to achieve the stated goal."

Virgin Galactic's mission design also contributes to maximizing safety, he added. SpaceShipTwo doesn't fire a rocket to launch into space until it's 50,000 feet up in the atmosphere, carried to that altitude by a mothership. And the spaceship lands on a runway, glider-style.

"That first and last 50,000 feet are handled through essentially well-established aviation technology," Whitesides said.

Making it happen

Whitesides expressed confidence that, given a few decades, human spaceflight can be as safe as many other modes of transportation. But getting there will be a process, he said.

That process is under way, and has been since Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space in 1961. And it's being furthered by the 400 or so people who have already put deposits down for flights on SpaceShipTwo, Whitesides said.

"These people are the ones who are stepping up and saying, 'I'm willing to put my money down, I'm willing to fly on the vehicles we have now,'" Whitesides said. "Obviously, it's our responsibility to make those vehicles as safe as we possibly can."

Human spaceflight at the moment may come with risks, but the potential rewards — exploring the solar system, and possibly establishing outposts on other worlds — are worth it to many people.

The important thing is to not undersell that risk, but rather to appreciate it, study it and work to minimize it as much as possible, experts said.

"If you're taking a risk with your eyes open and you understand it, then you can really forge ahead," Doremus said.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Return to SPACE.com each day this week for a closer look at the 25th anniversary of the Challenger space shuttle disaster.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.