NASA's Kepler mission has already found more than 1,200 potential alien planets, but it will likely be a few years before it hauls in the exoplanet "holy grail" – an alien Earth.

Scientists announced yesterday (Feb. 2) that the Kepler space telescope spotted 1,235 exoplanet candidates in its first four months of operation, including 54 that orbit their host stars in the so-called "habitable zone," that just-right range of distances that allow liquid water to exist.

While these finds are intriguing, none of the new planet candidates is likely to be a close Earth analogue, researchers said – even if a planet lies in the habitable zone, it may not be the same size and composition as Earth. Since our planet is the only world known to host life, finding and confirming an Earth twin could be a huge leap forward in the search for alien life.

"No one is more eager to get to that than the Kepler team," Douglas Hudgins, a Kepler program scientist at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., told reporters yesterday. "However, that's going to take time."

Making the finds

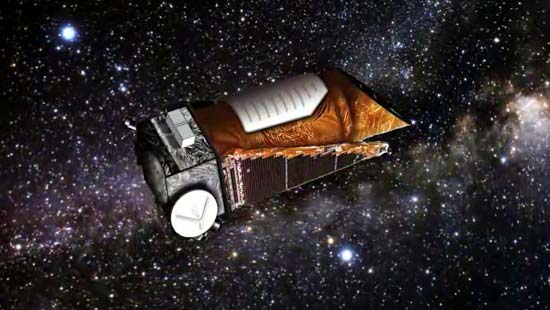

The Kepler space telescope, which launched in March 2009, finds alien planets by searching for tiny, telltale dips in a star's brightness caused when a planet transits — or crosses in front of — it from Earth's perspective.

The finds graduate from "candidates" to full-fledged planets after follow-up study — usually with large, ground-based telescopes — confirms that they're not false alarms. This process can take about a year. The Kepler team has already done a lot of vetting work on the 1,235 candidates, so most of them will probably pan out, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"My feeling is, it'll be better than 80 percent," Bill Borucki, Kepler's science principal investigator, told SPACE.com.

To flag a potential alien planet, Kepler needs to see a few transits, not just one. For that reason, it spots close-in planets more quickly and easily than planets found farther away, because the close-in ones move faster and transit more frequently.

And that's the pattern in the 54 potential planets — including the five that are around Earth's size — that Kepler found in their stars' habitable zones. The host stars are cooler than our own sun, and their habitable zones are thus closer in — which is where the planets are found.

Spotting an alien Earth

Finding an alien Earth — a rocky, Earth-size planet that orbits in the habitable zone of a sun-like star — will take longer than four months of observing. If intelligent aliens were studying our solar system, after all, they would see Earth transit just once a year.

"It'll require at least three years of Kepler data, as well as painstaking observations from some of the world's largest ground-based telescopes, before those types of planets are going to begin to emerge from the data," Hudgins said.

This is not to diminish the 54 planet candidates in their stars' habitable zones, or to imply that life cannot evolve on them. But if scientists are after a true Earth analogue — and many are — they'll probably have to wait a little longer.

Looking farther ahead

As productive as it's proving to be, Kepler still represents just one step — and an early one at that — in humanity's search for life beyond Earth, researchers said.

"We are in some sense the first generation," Borucki said. "We're finding them [planets]."

But new instruments will be needed to look for signs of life on the many worlds that Kepler discovers, researchers said. Scanning most alien planets' atmospheres for biomarkers, for example, is beyond the capabilities of today's instruments.

New missions, such as NASA's proposed Terrestrial Planet Finder — which would use an array of telescopes orbiting Earth to generate detailed images of alien worlds — could carry the search forward, Borucki said.

Making that happen would take money and require some patience. TPF, for example, is in limbo, with no firm funding and no launch date. So how Kepler's finds will be followed up remains a bit of a mystery.

"This is only one step," Borucki said. "It's an important step, but there are other steps that must follow."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.