Surprising Earth-like Clouds Found in Saturn Moon's Smog

In the dense smog of Saturn's largest moon Titan, one far dirtier than anything on Earth, scientists have uncovered a surprise — pearly white cirrus-like clouds much like the ones that can be seen in our skies.

These new findings shed light on how Titan's mysterious atmosphere works.

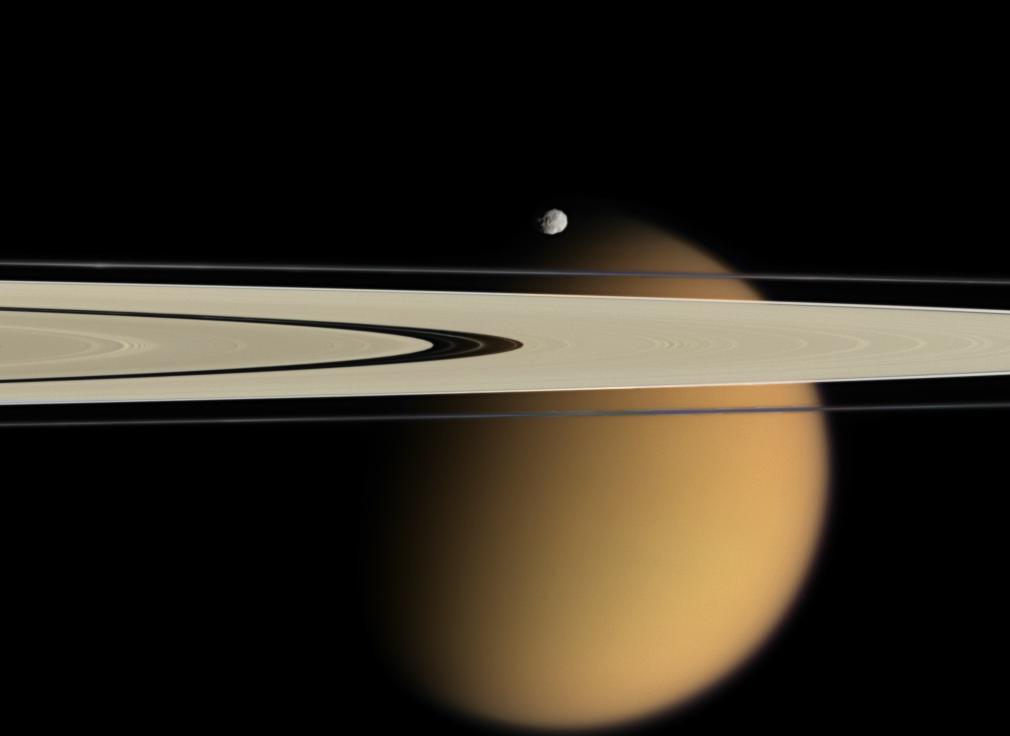

The smothering haze on Titan — once described as crude oil without the sulfur — hides every bit of the moon's surface, making it look like a dirty orange ball. Puffy clouds of methane and ethane — hydrocarbons better known for their role in natural gas — have previously been seen in this smog by telescopes on Earth and by NASA's Cassini spacecraft currently in orbit around Saturn. [Photos: Saturn's Rings and Moons]

Titan up close

When NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft flew by Titan in 1980, it detected hints that tenuous clouds of ice might lurk in Titan's stratosphere, the second-lowest layer of the moon's atmosphere — "ices made from some exotic organic compounds," said study co-author Robert Samuelson at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "At the time, that was about all we could tell."

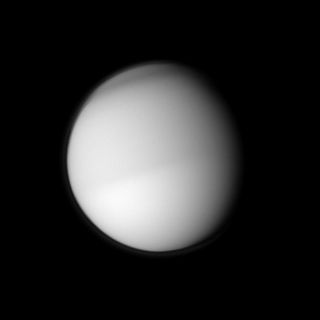

Now, using the Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) on Cassini, scientists have confirmed the existence of thin, wispy clouds made of exotic ices on Titan, similar to Earth's cirrus clouds, that are as pure white as fresh snow.

"They are very tenuous and very easy to miss," said study lead author Carrie Anderson, a space scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Anderson and Samuelson discovered these clouds through a series of observations near Titan's north pole, at latitudes that on Earth would fall just inside and outside the Arctic Circle. By gazing at the atmosphere at an angle — a longer line of sight that gives more data — they succeeded in separating out the delicate signatures of the ice clouds from the haze.

"That was convincing evidence," Anderson said. "What Voyager had seen was real."

The freezing temperatures needed to create the ices in these clouds occur in the "cold, cold depths of Titan's stratosphere," Anderson said.

The researchers conjecture that a mix of hydrocarbons or nitrogen-hydrocarbon compounds known as nitriles higher up in the atmosphere get moved downward by a constant stream of gas that flows from the pole in the warmer hemisphere to the pole in the colder hemisphere.

"The organic vapors simply condense out as they descend," Anderson told SPACE.com.

Anderson and Samuelson suspect the need for a cold hemisphere is why these ice clouds were spotted in the north. When Voyager flew by, the north had just crossed from winter into spring, and when Anderson and Samuelson first made their observations, they did so when the north was in mid-winter.

They also reasoned that the south should not lack these clouds, but it should have fewer of them.

Ice clouds on Titan

After checking Titan's southern hemisphere and both sides of the equator, the researchers did indeed spot these clouds in all three locations, although the clouds in the north were more plentiful, as predicted — in fact, they were found to be three times more plentiful.

At first, Titan's cirrus clouds seem entirely unrelated to clouds on Earth. Even if one ignored their exotic components, they form in the stratosphere, which is much higher in the atmosphere than in the troposphere, where nearly all Earth clouds are formed.

Still, Earth does have a few polar stratospheric clouds that appear over Antarctica and sometimes in the Arctic during winter. These clouds originate in the exceptionally cold air that gets trapped in the center of the polar vortex, a fierce wind that whips around the pole high in the stratosphere, and where Earth's ozone hole is found. Titan has its own polar vortex and may even have a counterpart to Earth's ozone hole.

"We are starting to find out how similar Titan's clouds are to Earth's," Samuelson said. "How do they compare? How do they not compare?"

Titan's atmosphere has long intrigued scientists, especially because some of the organic chemicals found within it are thought to be linked to the events that led to life on Earth. These findings shed light on the mysterious life cycle of these compounds.

"They fall to the surface, and it's a dead end, and yet Titan's atmosphere still has methane in it," Samuelson said. "We are trying to find out why."

A big test to scientists' understanding of these new clouds will come in 2017, when summer comes to the north and the south plunges into winter.

"We expect to find a complete reversal in the circulation of gas then," Anderson said. "The gas should start to flow from the north to the south, and that should mean most of the high-altitude ice clouds will be in the southern hemisphere."

Other major changes are in store for Titan then, including the disappearance of the fierce winds around the north pole.

"The big question is, will the vortex go out with a bang or whimper?" said Michael Flasar at NASA Goddard, the principal investigator for CIRS."On Earth, it goes out with a bang. It's very dramatic. But on Titan, maybe the vortex just gradually fizzles out like the smile of the Cheshire cat."

The scientists detailed their findings online in the Feb. 1 issue of the journal Icarus.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us